Campus & Community

The Franklin Street Gem

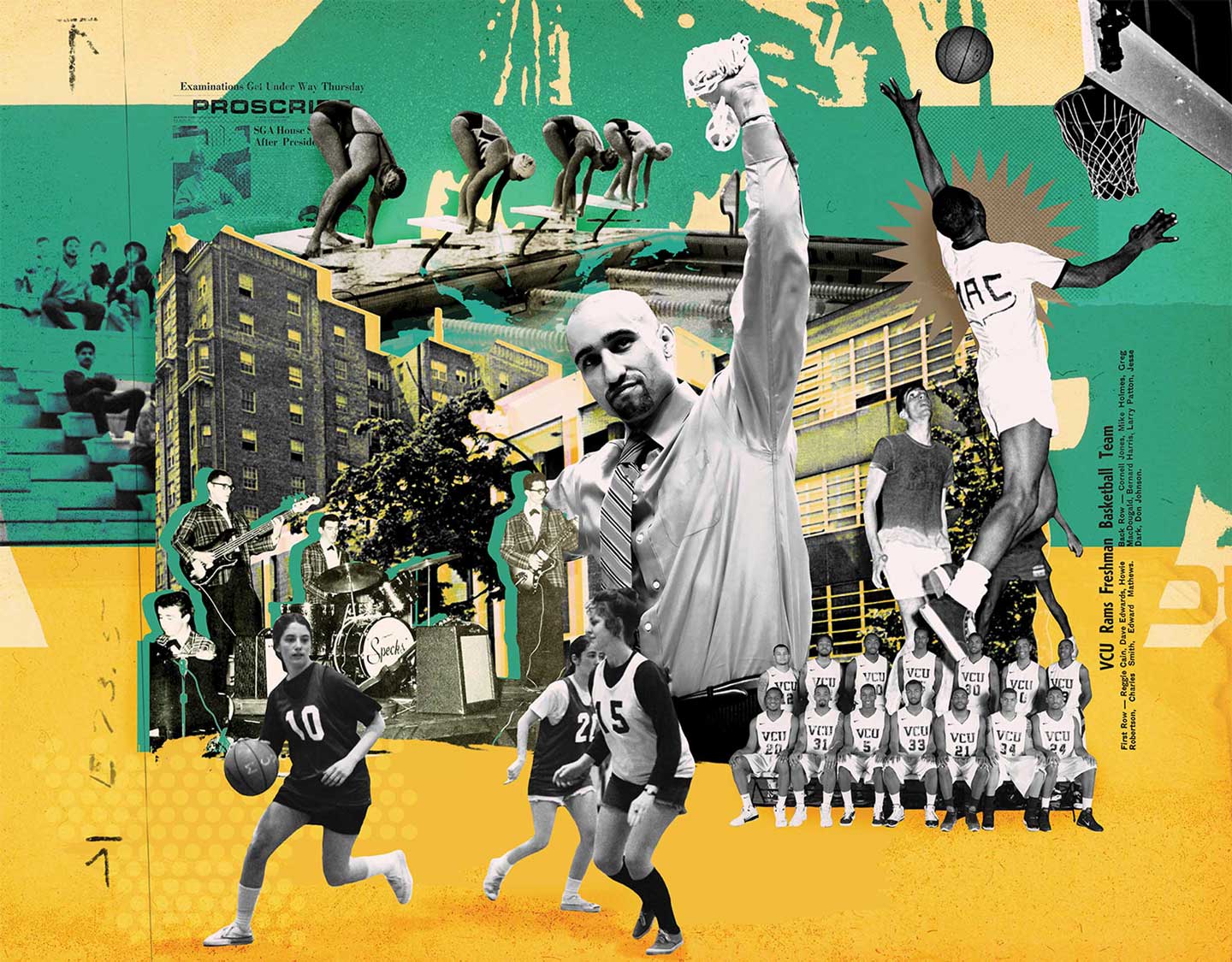

The concerts. The basketball games. The brushes with celebrity. Seventy years after Franklin Street Gym opened, two years after it was torn down and as a new building rises where it once stood, an ode to VCU’s beloved, sweltering, cubby-size gymnasium ... and all it witnessed.

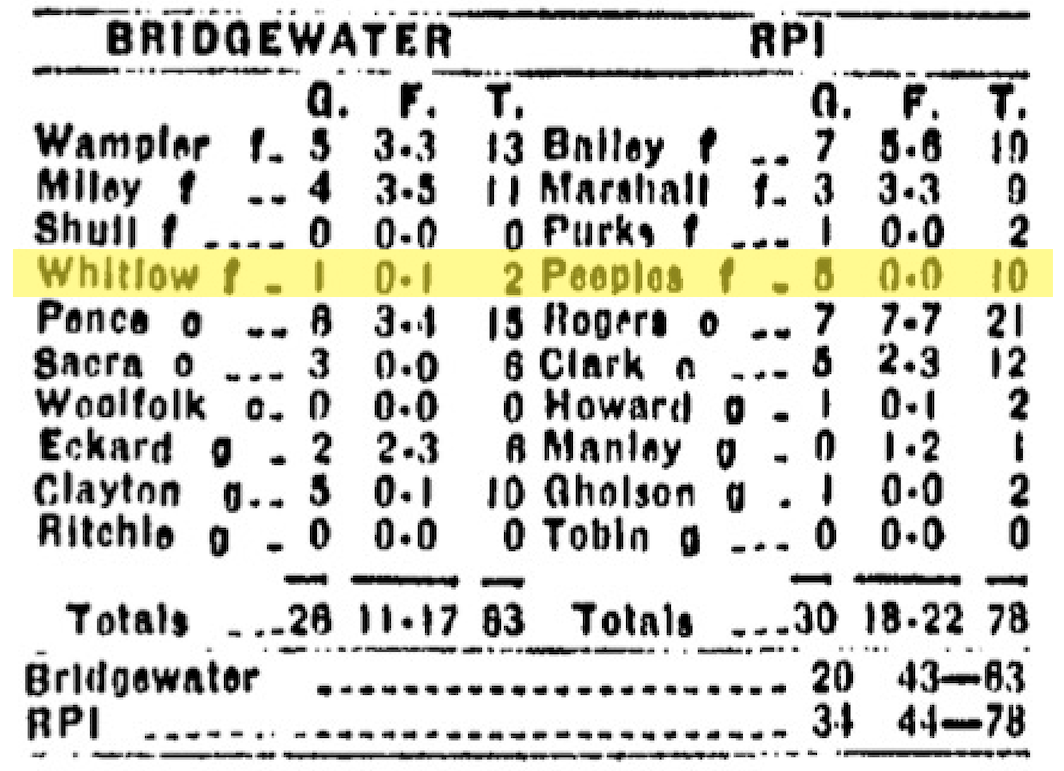

Carlyle Whitelow hopped off the Bridgewater College bench. Uneasiness filled Franklin Street Gym as he removed his warmup pants and jacket and prepared to enter this midseason basketball game against Richmond Professional Institute. It was 1956, in the Virginia state capital, and Whitelow was Black.

Twenty months earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. At Bridgewater, a tiny Shenandoah Valley private school that integrated in 1953, the ruling changed little. But elsewhere in Virginia, Brown triggered a backlash, and as Whitelow prepared to check in, legislators were working to harden the state’s segregation laws.

Whitelow, the first Black student to play sports for a predominantly white college in Virginia, knelt on the sideline, waiting for a pause in the game. Franklin Street Gym was a tight box with room for about 500 fans. Ed Peeples, Ph.D. (B.S.’57), scanned the crowd. He was a junior forward for RPI and a white Richmonder undergoing a moral awakening. A year earlier, calling out “separate but equal” for the farce it was, he had argued with RPI’s cafeteria manager for refusing to serve a meal to the Black bus driver of a visiting team. “He is our guest!” Peeples growled. “Where else can he eat?”

How ironic, Peeples thought as he watched Whitelow, that we must stop time to break the color barrier inside this tiny gym. Peeples, who died in 2019, was a future academic and civil rights activist and in 2001 wrote an essay about this game, an unremarkable meeting between teams with losing records. RPI defeated Bridgewater, 78-63. The Richmond Times-Dispatch devoted an uneventful 454 words to the recap the next day and included zero quotes. Whitelow’s name appears only once, in the box score, misspelled as “Whitlow.”

The buzzer sounded and Whitelow walked onto the court — “slowly, maybe even cautiously,” Peeples later wrote. He was the only Black person in the building except for Franklin Street Gym’s night watchman.

Peeples noticed many fans “were looking at each other as if to ask for a clue about how to respond.” Then, he wrote, “three or four individuals stood up slowly and began timidly to applaud.

“I joined them. In the next moments, more people began to stand up and clap, and then more, until every person in that gymnasium was on their feet offering their tribute to this lone brave black warrior.”

Ten days later, the Virginia General Assembly adopted a resolution defying Brown and laying the groundwork for its “massive resistance” against integration. Schools closed and universities blocked the enrollment of Black students. It would take a decade for many Virginia public colleges, including RPI (a precursor to Virginia Commonwealth University), to integrate their basketball teams.

Carlyle Whitelow graduated from Bridgewater College in 1959. In February 2022, four months after Whitelow’s death, a General Assembly of a different era issued a resolution honoring his life, recognizing that Whitelow “broke down color barriers both as a student and an athlete.” A small sample of his efforts unfolded at a basketball game in Richmond on Jan. 21, 1956. It was one of the first notable moments to take place inside Franklin Street Gym. It would not be the last.

(Richmond Times-Dispatch via NewsBank)

A misfit with a story

Franklin Street Gym was an unremarkable venue, cramped and claustrophobic, and wrapped in an exterior that was architecturally distinctive for all the wrong reasons. It also was a tabernacle for VCU basketball and a magnet for outsized names and personalities. It was born in 1952 and died in 2020, and witnessed enough in its 68 years to fill a small textbook: The poet Allen Ginsberg once inadvertently started a riot while giving a reading in Franklin Street Gym. The greatest victory in the early days of VCU basketball took place there. A young Bruce Springsteen watched the police arrest his drummer. Shaka Smart, the architect of VCU’s 2011 Final Four run, once almost set fire to its court.

From the beginning, it was obvious the gym would have more than a few encounters with fame. Ed Allen, RPI’s basketball coach from 1950-67, organized exhibition games at the new gym for statewide military personnel during the Korean War. Among the participants: baseball stars Willie Mays and Don Newcombe.

Franklin Street Gym was the first building the growing college, previously occupying only existing structures, ever built, “important in real terms and symbolic terms,” says John Kneebone, Ph.D., an associate professor emeritus in the history department at VCU. “It helped give an identity to the school.”

“It was kind of a marker that VCU existed,” he says.

Over the next seven decades — through two building expansions, the 1968 creation of Virginia Commonwealth University from the shuttering of RPI and the Medical College of Virginia and the rapid, sometimes tumultuous growth of VCU and its two campuses following that arranged marriage — the gym became a hub, home to physical education and art classes, offices, student dorms, a swimming pool, wrestling rooms, and basketball courts that doubled as concert venues. It was all rolled into “one long, extended modernistic wonder along Franklin Street,” says Edwin Slipek (B.F.A.’74), a Richmond-based writer and architecture critic.

Franklin Street Gym stood out, Slipek says, because of that architectural contrast: a cubic, International-style misfit, all red brick and glass, plopped in the middle of West Franklin Street’s Victorian and Classical Revival mansions. During a 1970 expansion of Franklin Street Gym, officials attempted to help the building better blend into the neighborhood, adding four faux-Classical columns to its northeast front. It hardly recalled Ancient Greece or Rome. No matter; it was what happened inside the walls that counted.

Slipek was one of several writers who penned tributes to Franklin Street Gym in 2019 and 2020, after VCU announced it would tear down the old landmark to make way for a six-story science, technology, engineering and math building. Those articles — from Slipek’s anecdote-flush farewell in Style Weekly to Eamonn Brennan’s ode to “the tiny, sweaty bandbox where VCU basketball was born” in The Athletic and Fred Jeter’s (B.S.’73) goodbye in the Richmond Free Press — amounted to a recounting of Franklin Street Gym’s brushes with celebrity: Mays and Newcombe, Alice Cooper and the Ramones, the painter Roy Lichtenstein and the dancer and choreographer Twyla Tharp.

The prevailing notion in those eulogies was that it was time to say goodbye. By 2020, when the wrecking ball took its cuts at Franklin Street Gym, the building’s longtime tenants had long since moved out. And the gym’s maligned architectural style made the argument for historic preservation impossible.

But, Slipek says, it’s important to remember Franklin Street Gym and preserve what happened there.

“[Franklin Street Gym] probably had more going on in its history than any other building on campus for its time period,” he says. “Personalities. And uses. And memories. And some of the great athletes and minds of our time.”

Franklin Street Gym. (VCU Libraries)

The Franklin Street ‘refuge’

Ask Charles McLeod, Ed.D. (B.S.’70; M.Ed.’73), about his memories playing basketball inside Franklin Street Gym and the first thing he’ll say is that the gym he remembers probably isn’t the gym you are talking about. That’s because McLeod didn’t play for VCU inside that Franklin Street Gym; he played for Richmond Professional Institute inside its predecessor.

The expansion of Franklin Street Gym in 1970 — the one that added those strange exterior columns — included the creation of a new basketball gym, a 1,500-seat, no-frills home for the VCU men’s team (the women’s team was created in 1974). Most VCU basketball fans, even diehards who have followed the program for decades, are hardwired to associate the Rams with this Franklin Street Gym. But McLeod enrolled at RPI four years earlier, and his Franklin Street Gym (the original gym where Ed Peeples saw Carlyle Whitelow) was more austere than its 1970 replacement: walls, a few rows of bleachers and the court itself. It opened to the cobblestone alley behind the building. “When people call it ‘Franklin Street Gym,’ we couldn’t see Franklin Street from where we were,” McLeod says. “And hot, man. It was a hotbox. It was a sauna. It was a matchbox. You had to pull up on a layup or you’d run into the wall right behind [the basket].”

McLeod was RPI’s first Black basketball player. He transferred to the school in January 1966 after a frustrating semester on the bench at Virginia State College (now Virginia State University). He was 19 years old, and his mother was a civil rights activist who had sued the Chesterfield County, Virginia, school district over segregation. McLeod’s first months at RPI were painful. “Loneliest time of my life,” he says. “I spent a lot of time at Virginia Union because there just weren’t a lot of Black kids at RPI. I was at Union so much that some people there thought I went to Virginia Union.

“Franklin Street Gym was my refuge,” he says. “I’d be over in that gym bouncing that basketball. I was there by myself, that spring semester ’66.”

He wasn’t alone for long. Ed Allen — and later Benny Dees, who succeeded Allen as basketball coach in 1967 — were building RPI into a formidable program by recruiting Black players. RPI, Old Dominion University and George Mason University integrated in 1965 and 1966, and the Rams pursued integration more aggressively than most Virginia schools. By 1969, VCU had four Black players. By 1970, the year Al Drummond became the first Black basketball player at the University of Virginia, the Rams had an all-Black starting lineup.

Donald Gordon, from Brooklyn, New York, and John Collins, from Richmond, enrolled at RPI in the fall of 1966. The following year, Donald Ross Jr. (B.S.’72), a high-scoring guard, transferred from Cleveland State University. Charles “Jabo” Wilkins arrived in 1968. Ross holds the school record for points in a game (55 vs. Old Dominion). Wilkins is fourth on VCU’s all-time scoring list. The talent jump was so abrupt, says Fred Jeter, a longtime Richmond sportswriter, that five players on VCU’s 1968 team were playing intramurals the next season.

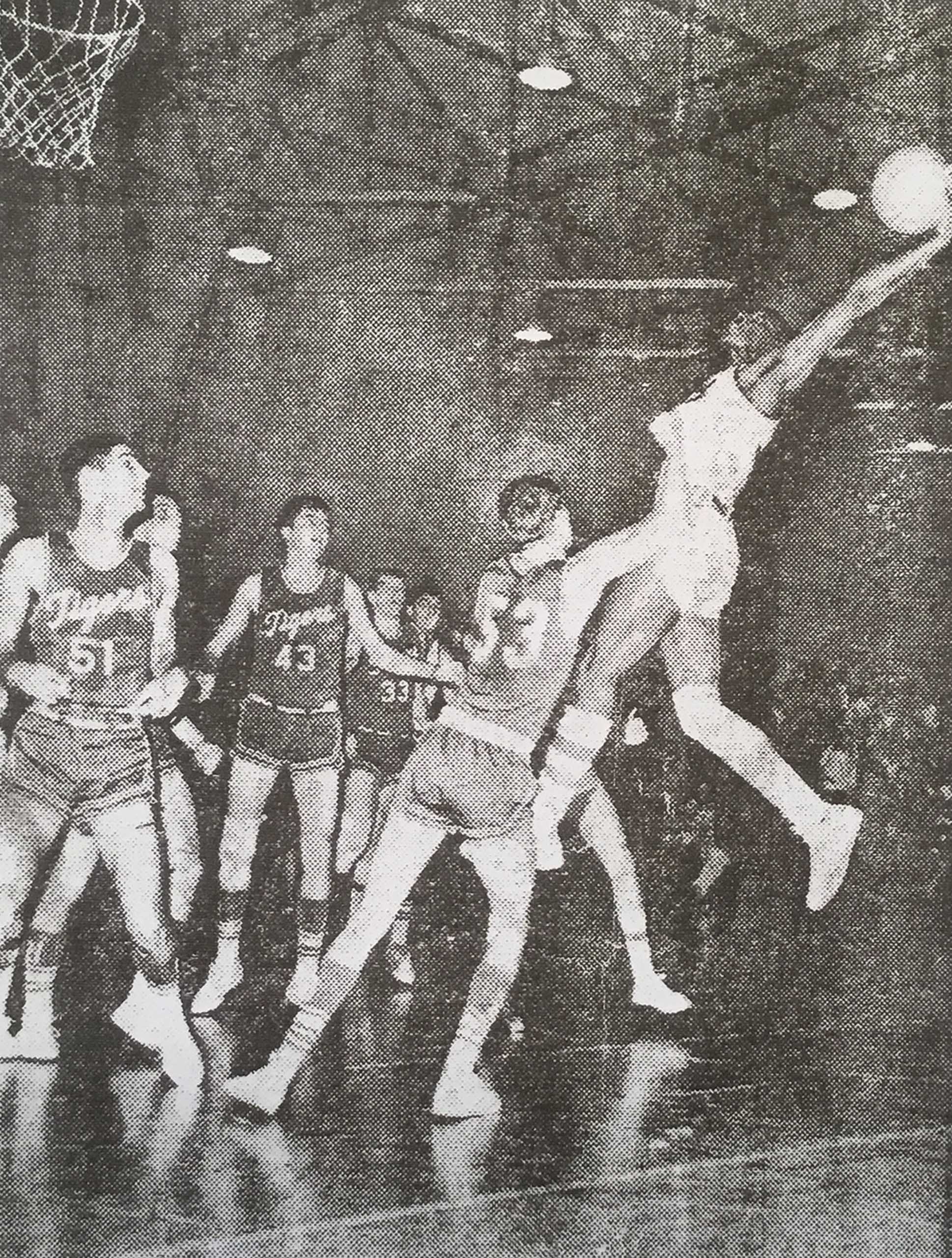

McLeod pulled down rebounds, blocked shots and played defense. His teammates called him “Charlie Mac the Jumping Jack.” There’s a photo of him from a 1967 game against rival Hampden-Sydney College that tends to recirculate. It’s McLeod’s favorite game — RPI won, 79-73, in overtime — and his favorite image. He’s 2 feet in the air, one-handing a rebound, his left arm fully extended, like he vaulted off the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. A group of white Hampden-Sydney players stand flatfooted around him. The photo is almost kinetic, as though McLeod will actually start moving if you stare at him long enough, as though the ball is leading him somewhere new, out of the frame and out of the game, beyond Franklin Street Gym’s brick walls.

RPI trailblazer Charles McLeod pulls down a rebound against rival Hampden-Sydney College in 1967. (Courtesy of Charles McLeod; original Richmond Newspapers Inc.)

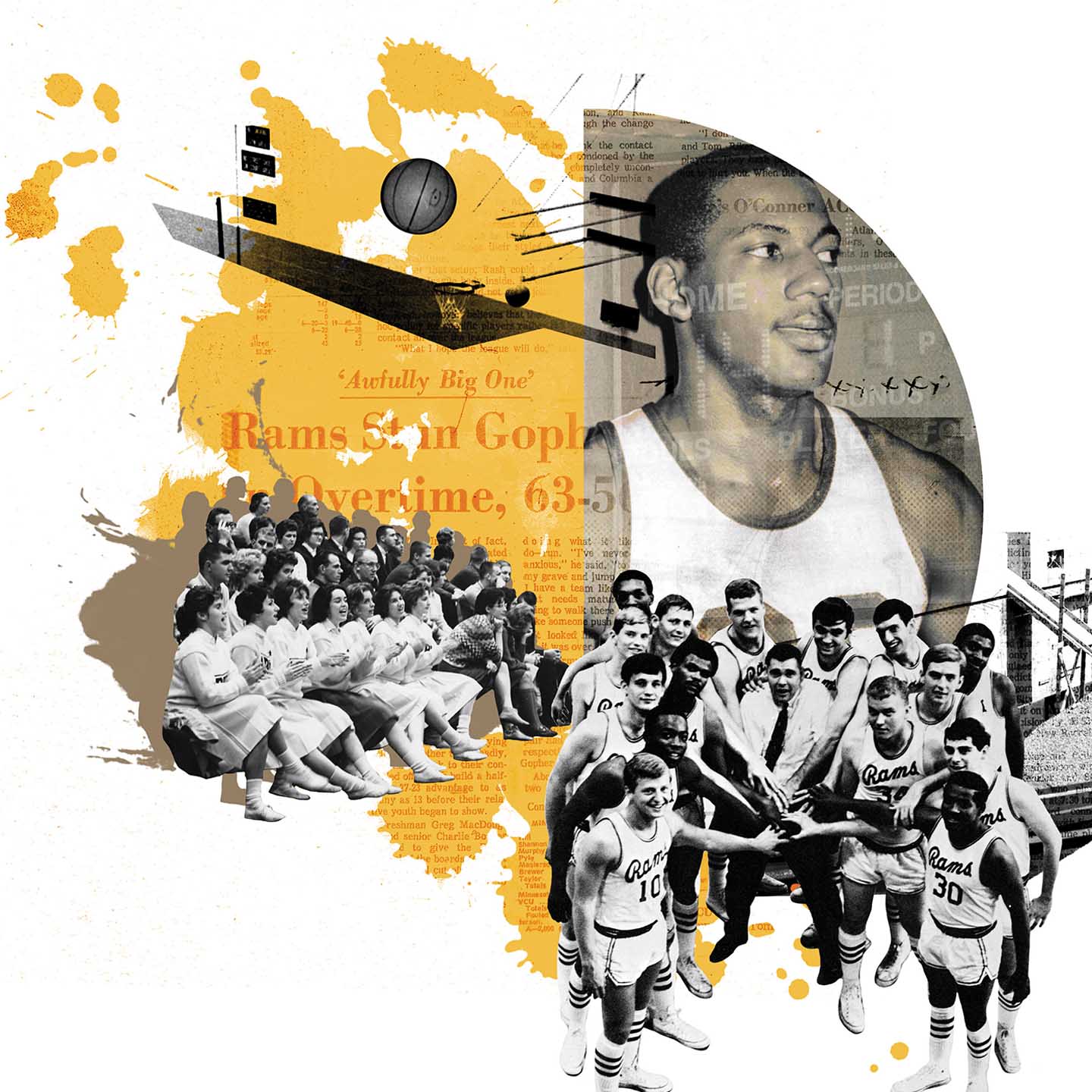

Minnesota mystery

Fred Jeter worked in VCU’s embryonic sports information office as an undergraduate student in the early 1970s and is as good an authority on the early days of VCU basketball as anyone. But even he doesn’t have a good explanation for one enduring Franklin Street Gym mystery: why the University of Minnesota was in Richmond to play VCU on Dec. 28, 1970.

“A lot of people didn’t believe the University of Minnesota was coming,” Jeter says. “Maybe Minnesota Northeast, something like that? Minnesota-Mankato? But it was the Minnesota Gophers.”

It’s Franklin Street Gym’s most famous game. VCU was 2 years old, and its basketball team was moving up to NCAA Division I from the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics, with a home schedule that included games against Bluefield State, Campbell and Haverford College. Minnesota was a founding member of the Big Ten Conference and had been playing basketball since Orville and Wilbur Wright were a couple of unknown bicycle manufacturers.

The game, though, was a trap. VCU’s 1970 recruiting class was its best to date: a quartet of New Yorkers — Reggie Cain (B.S.’78), Howie Robertson (B.S.’75), Greg McDougald and David Edwards — alongside Richmond native Jesse Dark and 6-foot-10 forward Bernard Harris. Dark and Harris would become VCU’s first NBA players, and most of the new class had declined offers from schools with better pedigrees, choosing to come to VCU and build something new. Their senior year of high school, Robertson and McDougald played in an all-star game in Philadelphia with some of the country’s best players, including Len Elmore, Tom Henderson and Tree Rollins. “I scored 25 points in the second half and the coach from Southern California came to my [hotel] room and offered me a scholarship,” Robertson says. “I said I was already committed to VCU. And he said, ‘VC-Who? Where is that?’”

Robertson believes the Gophers thought they were playing at Virginia, not Virginia Commonwealth — that through some bizarre clerical error or misunderstanding the Gophers either wound up in the wrong place or were surprised when they wound up in the right place. Why else would this game exist? Minnesota’s home arena could seat 18,000 people. VCU? Well, the new Franklin Street Gym was … new.

“Practice is over, and now volleyball is in there. In daytime it was the [campus] recreation department and at night it was a community center,” Cain says of the gym, which was in constant use and still didn’t have air conditioning. “We met folks from all over the city who came in and played pickup games. Lots of friendships, lots of guys who invite you into their homes, to their parties. It was a place to meet.”

Cain doesn’t think the Gophers mistook VCU for the University of Virginia, or that their pilot overshot the airport in Charlottesville by 80 miles. He thinks Minnesota was looking for a game against a team like Virginia and in Virginia, and landed on VCU casually — like they were choosing a pastry to devour. “As I understand it,” Cain says, “when they got to the gym for shootaround, they joked, ‘Oh, we must be playing a high school team.’”

Jeter estimates Franklin Street Gym was “about 80%” full on game night. It was winter break. VCU had advertised the game in the newspaper, instructing people to “Call Coach Allen … for

Advanced Ticket Sales.” The Gophers entered Franklin Street Gym in their maroon-and-gold uniforms. And then Minnesota, a basketball program nearly as old as the sport itself, with a future first-round NBA draft pick in the starting lineup, lost to VCU, 63-56, in overtime.

The myth of the (maybe) accidental Minnesota game is likely fiction. Chris Kowalczyk (M.S.’08) has worked in VCU’s sports information office since 2005 and a few years ago, he asked Jerry Pyle, a former Minnesota player, about the game; Pyle told him the Gophers knew the difference between Virginia and VCU. It still doesn’t answer Jeter’s question: Why did Minnesota agree to the game in the first place? Jeter suspects he might never know.

“I’ve never figured out why they agreed to come and play that game,” he says.

‘We felt invincible there’

Two things happened after the Minnesota game: No premier Division I basketball team worth its athletics logo wanted to schedule a game with VCU (the Rams, playing without a league, played just 19 games the following season and wouldn’t be able to schedule a full 30-game season until joining the Sun Belt Conference in 1979), and the stories about or taking place inside Franklin Street Gym, from the charming to the surreal, continued.

There’s the Old Dominion story, in which the Monarchs traveled to VCU on Feb. 10, 1971, and their fans, about 200 of them with tickets in hand, arrived to find Franklin Street Gym full, their seats given away before tipoff. “They wouldn’t let them in,” Jeter says. “I was inside and I heard something going on outside the doors, and it was the Old Dominion fans, infuriated. VCU sold them tickets, but on game night, they just let fans walk in, and they didn’t save the seats for the Old Dominion people. It was very poor management. I don’t think VCU was accustomed to large crowds [yet].” The teams, already rivals, wouldn’t schedule each other again until 1977.

There’s the Steven Kessinger story, a proxy for the (likely) countless times an unassuming student ran into a VCU basketball star on the court. Kessinger (B.S.’77) first walked into Franklin Street Gym in September 1973, at the start of his freshman year, looking for a pickup game. Several were in progress and “rather than wait for an opening, I noticed there was one basket where there was no game, just a few guys casually shooting.” Kessinger joined them, but “quickly realized I was out of my league.” He later learned he’d just met Jesse Dark and teammates. Nine months later, Dark signed a contract with the New York Knicks.

Then there’s the west basket. For years, a rumor circulated that it was 11/2 inches shorter than the standard 10-foot height.

Real? Fable? “I know it for a fact,” Jeter says. He remembers the floor beneath the west basket being “all worn out” because everyone coming to the gym for pickup games wanted to play at that end. And he remembers an assistant coach from the University of Richmond women’s team — around 1980, he thinks — requesting to have the basket measured. Sure enough, it was an inch and a half short. “It’s an amazing thing,” Jeter says, laughing. “It’s hard to believe this stuff.”

But that was a decade after the new gym opened. Was it always that way? Perhaps, like so many basketball stories inside Franklin Street Gym, it’s truth seasoned with a pinch of legend. “I always felt that one was a little bit shorter,” Reggie Cain says. “It could be perception. But I could not dunk until I dunked on this basket, and I couldn’t dunk on the other one. I believe one was a little shorter, just a tad.”

Franklin Street Gym’s “place for all” purpose — as home for VCU basketball, the university’s recreation building and a local community center — gave it charm and a town hall vibe. Cain would meet someone in a pickup game, run into them outside the gym after practice and then see them in the crowd on game night. “We knew everybody from rec ball, and we had a great relationship with the student body,” Cain says. “[And] Jesse, local hometown hero, he might have introduced us to half of Richmond.”

Beginning in 1971, men’s basketball started scheduling “bigger” games at the downtown Richmond Coliseum (the Rams moved to the Coliseum exclusively in 1980). After the Minnesota win — with VCU recruiting well, struggling to fill the schedule with quality opponents and playing in front of a crowd of classmates, friends and neighbors — the Rams overwhelmed teams inside Franklin Street Gym, amassing a 59-1 record from 1970-79. “We felt invincible there,” Howie Robertson says.

“We just couldn’t, or wouldn’t, lose,” Cain says. “Not in front of our fans. Not here. Look, we had to get up and walk the streets with these folks tomorrow. We couldn’t have them see us lose that night.”

The poet and the Boss

Allen Ginsberg was inside Franklin Street Gym on Oct. 12, 1970, giving a performance befitting his status as a longtime spokesman for alienated youth, blasting the Pentagon over Vietnam, describing his perceptions “while in the fifth hour of an LSD trance” and inviting the audience to join him in singing “Hare Krishna.” It was a Monday night, and all hell was about to break loose.

About 1,500 people had crowded into the building to see the Beat Generation poet and counterculture idealogue. Ginsberg spoke for two hours, and toward the end, someone passed him a piece of paper and he read it to the audience. It promoted a “Ginsberg Ball” block party later that night on Grove Avenue.

Franklin Street Gym mostly sat on the periphery of both formal activism and impromptu protests, rallies, demonstrations and civil strife. But on this night, the hundreds of people leaving Ginsberg’s reading went to the Grove Avenue Republic, a loose federation of loud, late-night, block-partying people living in houses just west of campus. They had a reputation for “bringing the police down on themselves,” John Kneebone says. They did that night.

The fuzz, lured by a rock band and beer-lubed revelry, arrived with clubs and dogs. Bottles, cans and bricks sailed through the air. Someone spray-painted the words “Pig” and “Anarchy” on a police cruiser. The cops arrested 17. At least a dozen people were injured. “The president of the university had to come and try and bring peace,” Kneebone says. “They even went to [Ginsberg’s] hotel room and got Ginsberg to come back and guide part of the crowd to Monroe Park, where he led them in chanting and meditation.”

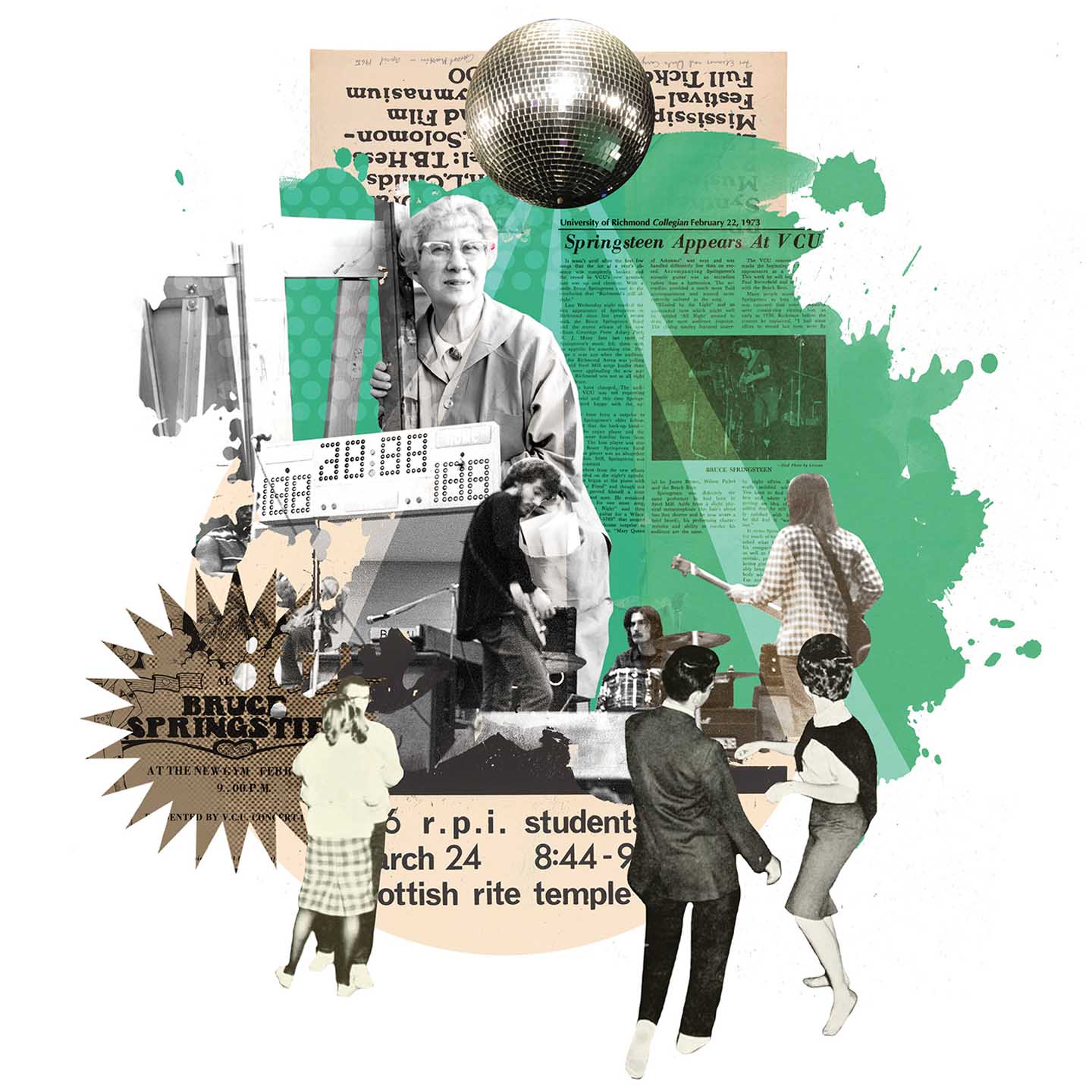

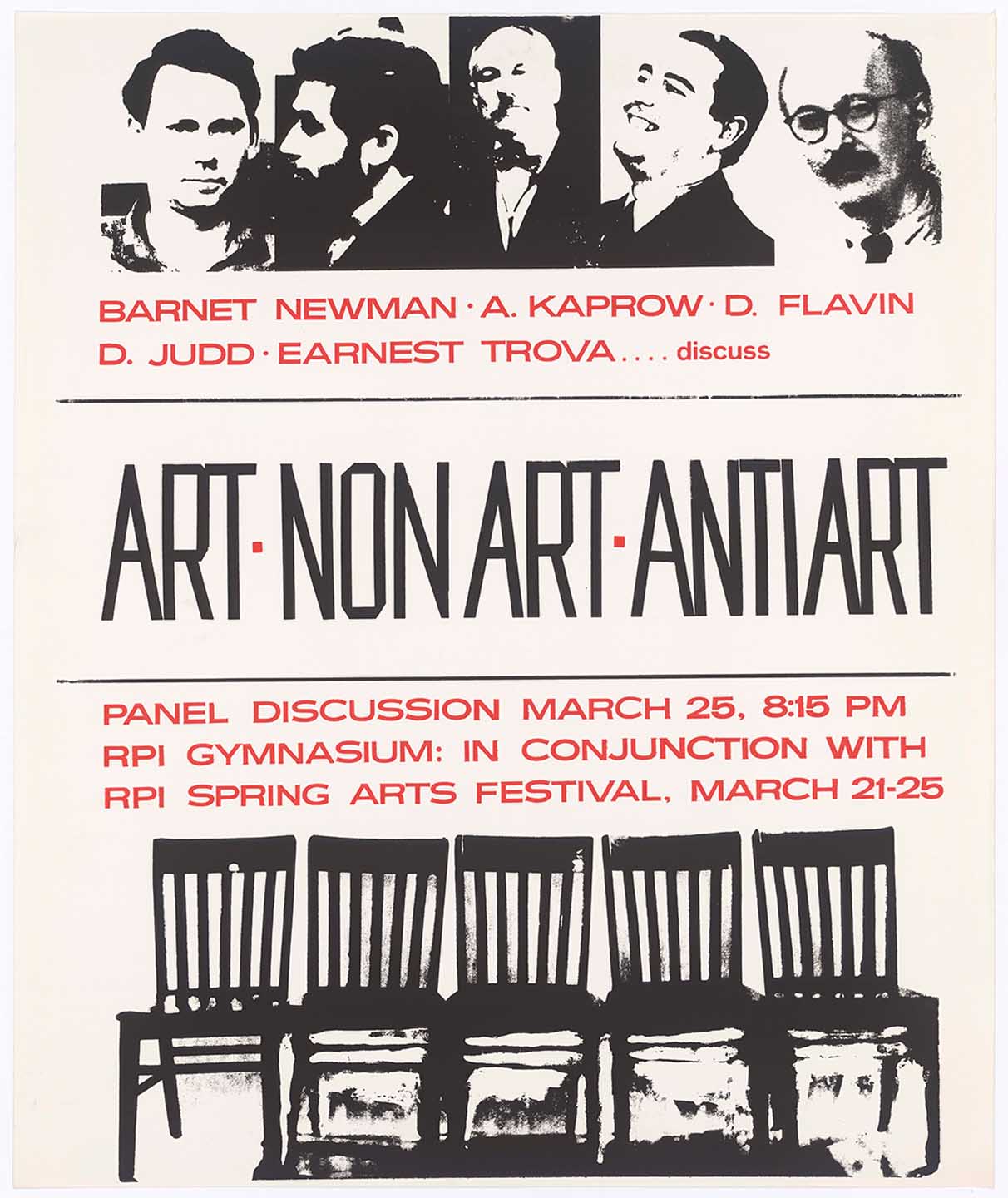

Ginsberg was not the only, or the first, celebrity to headline a university event inside Franklin Street Gym, though the Ginsberg Ball is “probably the most notorious spillover” from the building to the streets, Kneebone says. As it aged, Franklin Street Gym became an unofficial cosmopolitan hub. In 1964, a group of RPI professors began hosting Bang, an annual arts festival, inside the gym, and over the next four years, a flood of artists, musicians, dancers and authors came to Richmond, including blues singer Jesse “The Lone Cat” Fuller, painters Larry Rivers and Roy Lichtenstein, authors Allen Solomon and Tom Robbins (B.S.’59), dancer Twyla Tharp and an 18-year-old rock musician named Bruce Springsteen.

Bang, an annual arts festival hosted inside Franklin Street Gym, brought a flood of artists, musicians, dancers and authors to Richmond in the mid-1960s. (VCU Libraries)

The festivals coincided with VCU’s emergence as a national arts powerhouse and kicked off Franklin Street Gym’s heyday as the university’s music, arts and entertainment center. Kenny Rogers and the First Edition performed there. So did Alice Cooper. The Ramones played the building at least twice, at Halloween shows in 1976 and 1978. Robbin Thompson and Steve Bassett, who wrote the lyrics to “Sweet Virginia Breeze” on the front porch of Thompson’s Richmond home, headlined shows inside Franklin Street Gym.

Mention any number of these concerts, and the memories start pouring out — of a setlist, an outfit, a chance encounter. The latter could happen in quiet moments, too: In 1973, a VCU dance instructor named Tanya Dennis, sitting alone in a wrestling room inside Franklin Street Gym and playing a conga drum, caught the attention of a curious student, Renée Knight Lacy (B.S.’78), and before the night was over Dennis and Knight Lacy had formed the Ezibu Muntu African Dance Company, which starred in the music video for the Dave Matthews Band song “Stay.”

Then there was Springsteen. His appearance at Bang kicked off a long run of shows in Richmond from 1969-75, most with a band called Steel Mill. At least three of those shows were at Franklin Street Gym. The second, May 23, 1970, is campus folklore. Springsteen was 20 years old and his hair was down to his shoulders, and he played a gold Les Paul with the finish removed (replaced with clear surfboard resin) to expose the wood underneath. He and Steel Mill had the crowd in a frenzy. The contract for the concert called for the gym to be vacated at 11 p.m. Steel Mill was still playing when security cut the power to the building. But Vini Lopez, Steel Mill’s drummer, kept playing until he was wrestled to the ground and arrested.

Three years later, Springsteen was back, opening a Valentine’s Day show for Dan Hicks and The Hot Licks. Bassett was in the crowd that night. So was Susan Walthall (B.S.’77). She and her date were there for the headliner, but it was Springsteen, now playing with his newly formed E Street Band, that Walthall remembers most.

“They were just releasing their first album,” she says. “They were the best band I had ever heard.”

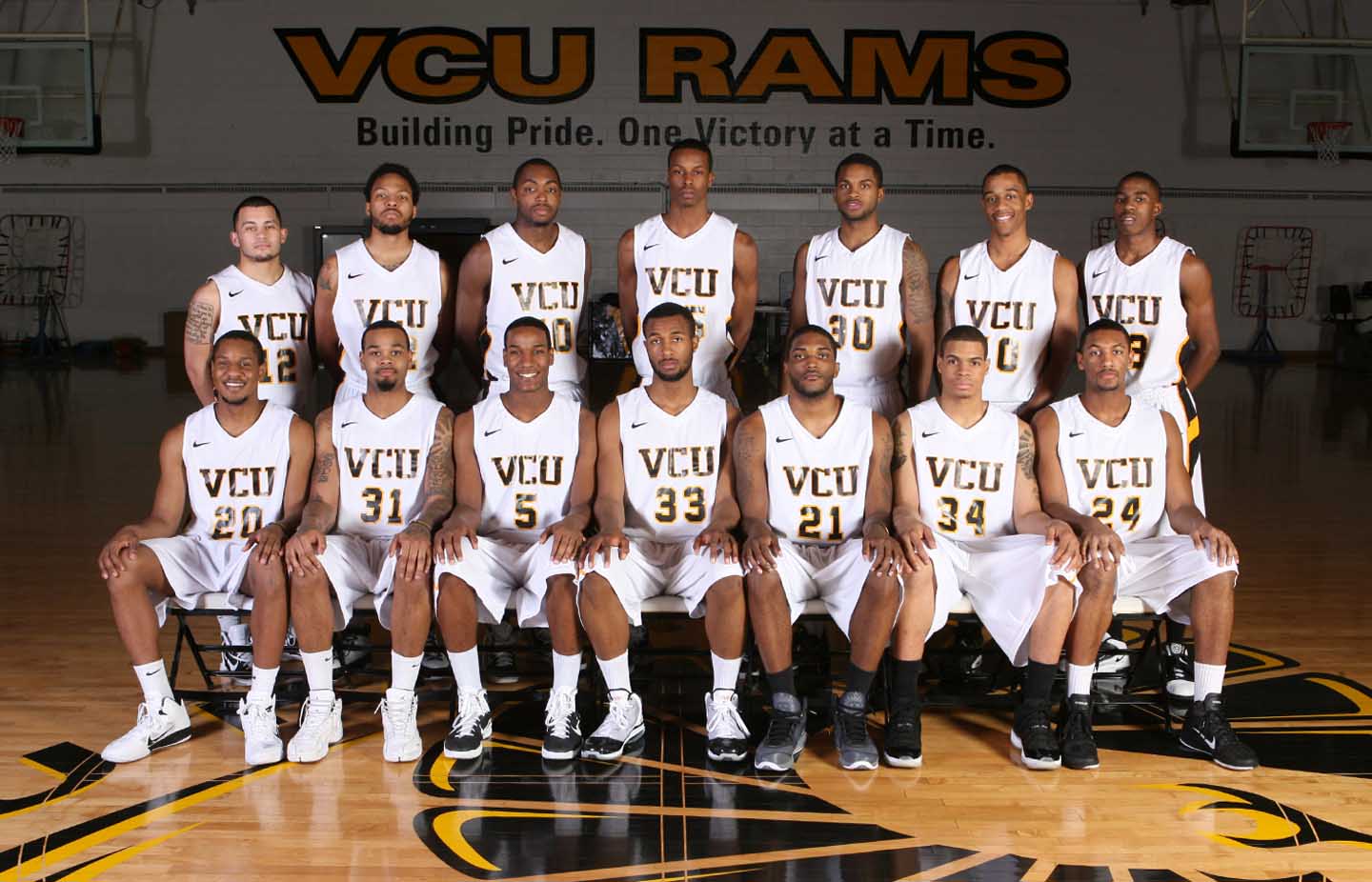

The 2010-11 VCU men's basketball team. (Courtesy of VCU Athletics)

‘The hottest spot in Richmond’

Shaka Smart walked into Franklin Street Gym holding a metal wastebasket and a large sheet of paper. It was March 2, 2011, and the second-year VCU men’s basketball coach needed to reset his team, which had closed February by losing four of five games.

Franklin Street Gym’s outsized role in campus life had diminished over the previous 30 years. Though it was still a busy place in the 1980s and ’90s — home to bleary-eyed journalism students editing video, swim meets and water polo matches in the basement pool, PE classes and pickup basketball — the university had outgrown the old gym. By 2009 when Smart arrived, 30,000 students attended VCU (up from about 2,000 when Franklin Street Gym opened in 1952), and new buildings had absorbed most of the gym’s activities.

VCU basketball, though, had never truly left its old haunt. Despite moving their home games out of Franklin Street Gym in 1980 — first to the Richmond Coliseum and then to the Stuart C. Siegel Center — the Rams still practiced there. Smart’s first impressions: It was “a pretty cool old gym” that “wasn’t very nice.” He wondered why the Rams didn’t practice at the Siegel Center instead. But in time, he realized no other VCU teams regularly used the building, and what Franklin Street Gym lacked in plush amenities, it made up for by being primordial — and always available — to VCU basketball.

“To play at VCU you had to be tough, you had to be gritty, you had to be competitive. And Franklin Street Gym was all those things,” Smart says. Rather than move practices out of the building, he encouraged his players to spend more time there and eschew Richmond’s nightlife. He started calling it Club Franklin. “It’s the hottest spot in Richmond and we got shots 24 hours a day,” he quipped.

It was a cheeky moniker and a bit of a pop-culture renaissance for a dusty old gym entering its seventh decade. Smart even turned it into a T-shirt. (“I still have mine,” says Bradford Burgess (B.S.’12), who played for VCU from 2008-12.) And in the final weeks of the 2011 season, Smart again stepped inside VCU basketball’s sweaty crucible, trying to find another way to inspire a team gone awry.

The players were sitting around him on folding chairs. Smart held up the oversized sheet of paper — the February page from his desk pad calendar. “I said we had to put February behind us. February is over,” Smart says.

“And then I set the thing on fire.”

“He pulled a lighter out and lit it up,” Burgess says.

The flames quickly consumed Smart’s calendar and he dropped it into the wastebasket. Well, most of it. Part of the calendar “didn’t go in the wastebasket, it kind of went on the side of the wastebasket,” Smart says.

“It’s one of those things where if you ask for permission you probably would get a ‘No,’” he says, laughing. “I’m usually a pretty risk-averse person, but I thought we could manage it. It’s not like it was a bonfire.”

The fire burned out without damaging anything else. The Rams won their next two games, lost in the Colonial Athletic Association championship to Old Dominion, and squeezed into the NCAA Tournament with one of the last at-large bids. And then, pegged as a team that did not belong, they embarked on one of the greatest runs in the history of college sports, winning five games to reach the Final Four and coming within one victory of the national championship game.

“It was a symbolic moment of moving on and letting things go. We felt rejuvenated,” Burgess says of Smart’s demonstration.

He laughs.

“I think [the gym] would have held strong if the fire got out of control. I don’t think Franklin Street could burn down. That place had to get knocked down.”

A long goodbye

India Urbach was on campus in the summer of 2020 as the heavy machines demolished Franklin Street Gym. For the past 21 years, Urbach has worked in human resources for VCU’s College of Humanities and Sciences. She’s also the building manager for Founders Hall, at 827 W. Franklin St., about 300 feet from where Franklin Street Gym once stood. During the first summer of the COVID-19 pandemic, Urbach drove to VCU at least once a week to help prepare for the return of in-person activity on campus, taping public health signs to doors and windows and placing hand sanitizer and face masks at workstations.

Sometimes her husband joined her. India and Bob Urbach (B.S.’84; M.S.W.’86) met Oct. 27, 1978, at a Halloween party inside Franklin Street Gym, and now, bit by bit, they watched the excavators reduce the building to rubble. “When they took the part of the building down that faced west and the gym was open [to the outdoors] we said, ‘Oh, there we were,’” India says. “We did a lot of reminiscing.”

One afternoon, Bob walked down the alley in back of Franklin Street Gym, scaled a chain-link fence and retrieved a brick from the demolition site. It’s now in the front garden of the Urbachs’ home, “with other mementos of our life together,” India says. “Forty-two-plus years and counting.”

Take a walk on West Franklin Street today and the piece of land that once held Franklin Street Gym still stands out amid those retrofitted mansions. VCU’s science, technology, engineering and math building will open there in 2023. “There really ought to be a display case or history wall or timeline [inside the new building] that could show the connection among the cultural, political, musical, athletic and architectural forces of Franklin Street Gym,” Edwin Slipek says. “You could do a wonderful linear timeline, a permanent installation in the building, that would include all these names and dates.”

Maybe Shaka Smart’s flaming calendar story would be told in such a display. Certainly the concerts and shows would be there: The Ramones, Springsteen, Alice Cooper. There would be a section for VCU basketball, where you could read about the Minnesota myth, Bernard Harris and Jesse Dark, and how Reggie Cain could only dunk on the west basket. Tanya Dennis and Renée Knight Lacy would be there.

The Bang festivals. Charles McLeod.

Ed Peeples. Carlyle Whitelow.

“The building is gone,” John Kneebone says, “but the ghosts and the stories survive.”