Research & Discovery

The American streetcar’s legacy is its neighborhoods

Though electric street railways were ripped up and paved over, many of their namesake “streetcar suburbs” remain popular and vibrant.

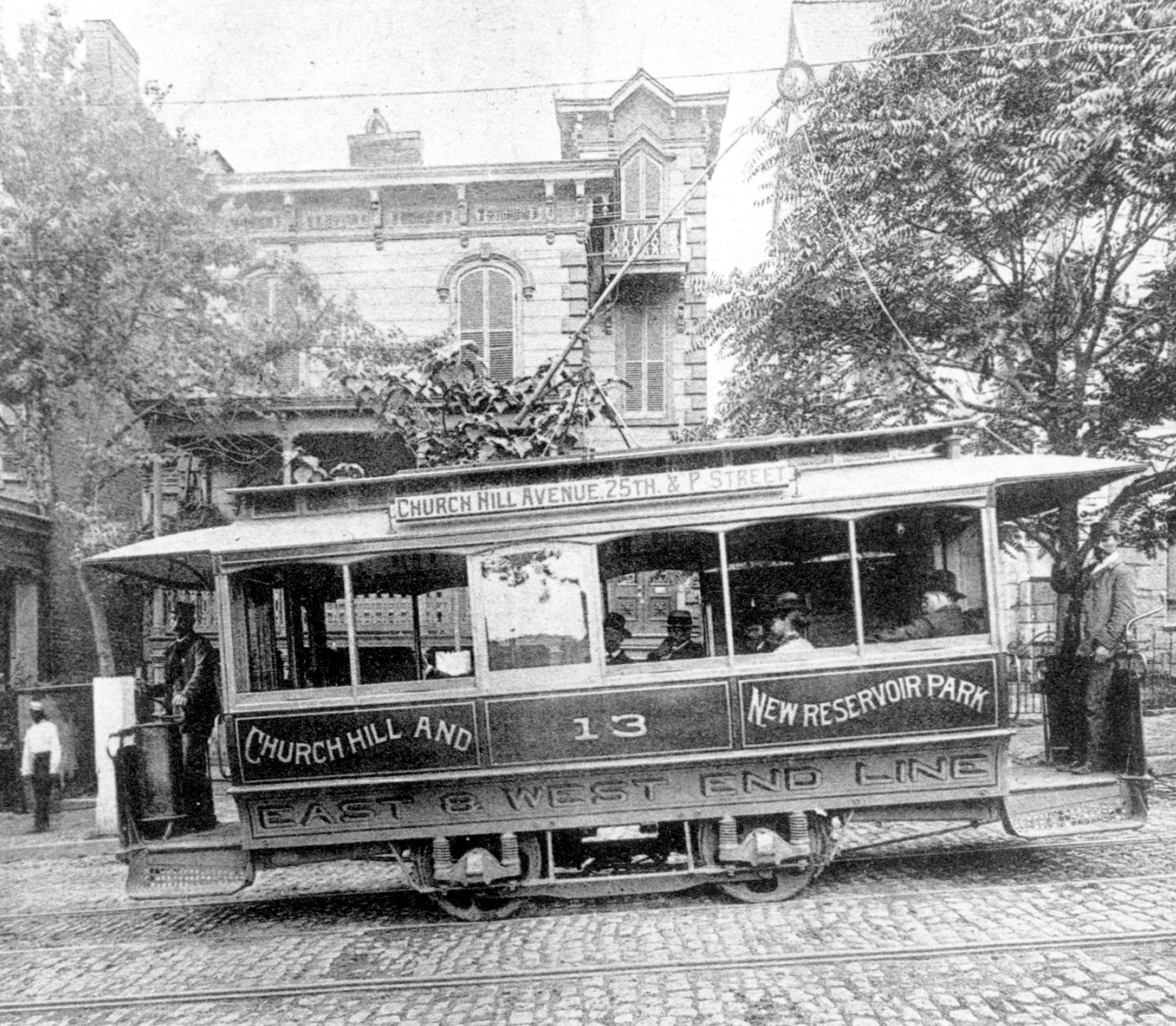

Richmond, birthplace and destroyer of the world’s first electric street railway (“A streetcar undesired,” Winter 2025), is also home to some of America’s first streetcar suburbs. And though the railways are long gone, many of the neighborhoods thankfully remain.

Compact, leafy and built near their namesake transit lines, these locales (Richmond examples include Ginter Park, the Fan, the Museum District and Forest Hill Park) occupy a sweet spot — in age, density, look and feel — between congested downtowns and car-centric, post-World War II sprawl. Most are at least 100 years old. Fire up Google Maps, pan to a gridded edge neighborhood of a major U.S. city and you’re likely looking at a streetcar suburb.

These neighborhoods typically are collections of row houses, duplexes, single-family homes and some retail shops, stitched together by a latticework of sidewalks and plenty of street trees, says Jim Smither, an assistant professor of urban design at VCU’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs.

“The densest streetcar suburb we have in Richmond is the Fan. The next is the Museum District and then some on the Northside,” he says. “I live in Ginter Park Terrace [in Northside], which was directly on the streetcar line.”

In addition to the sidewalks, density and a mix of properties, Smither — who holds master’s degrees in urban design, urban and regional planning, and landscape architecture — says finer design details have helped these neighborhoods retain their charm and popularity long after the streetcars stopped running.

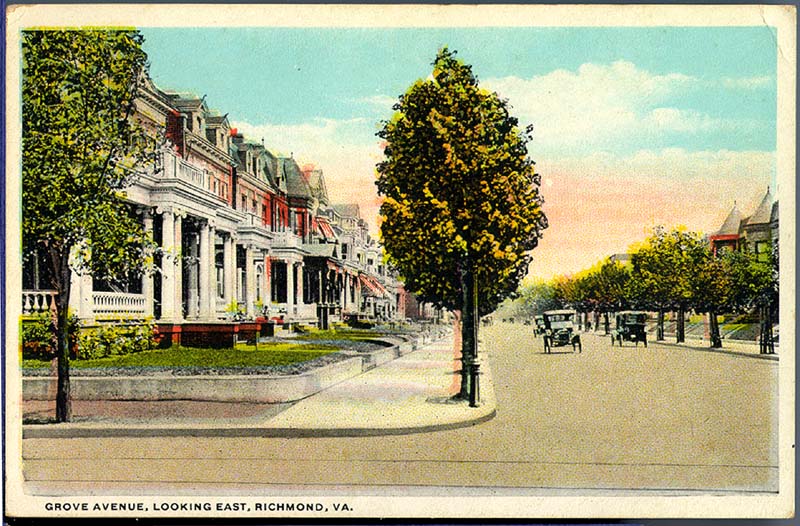

This early 20th century postcard from VCU Libraries’ Shuman postcard collection places viewers on Grove Avenue in the Fan looking east toward downtown.

Front porches

Streetcar suburbs have a pretty good “public realm,” Smither says — by which he means the space not occupied by buildings where people interact, like sidewalks, streets, parks and plazas.

But one of the most important places in streetcar neighborhoods is a sort of liminal space between the public realm and private property.

“Homes in streetcar suburbs have porches, which allow for engagement with neighbors or people passing by,” Smither says. “And you sort of have control of that porch. You can either stay out there or stay inside. There’s a negotiation that happens between the public realm and the private realm on the porch.”

Smither’s house is set back about 25 feet from the sidewalk, but if you go to the Fan, he says, the homes are closer to the street, some only about 10 feet back.

“I actually prefer my particular setback,” he says. “I’m not as social, so I don’t hang out on my porch, but lots of people in my neighborhood do. And when I go over to my partner’s house, she and I sit on the porch and we say hello to people, and some people come up and greet us on the porch. The porches provide signs of humanity.”

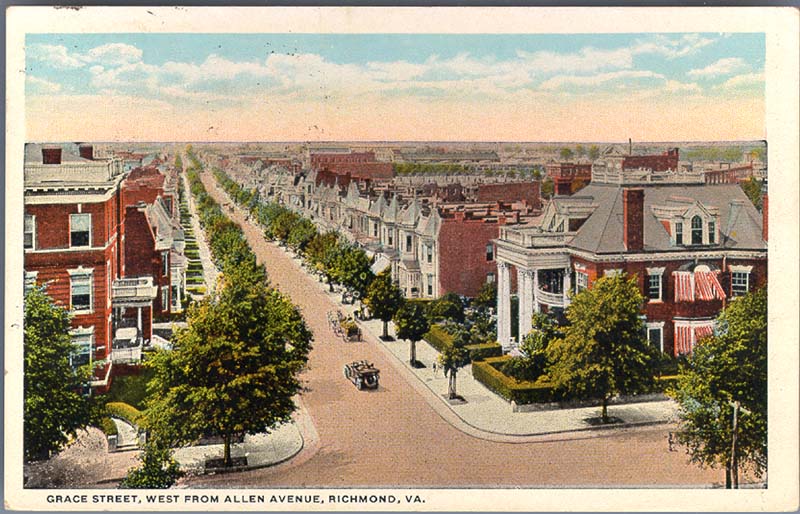

Another turn-of-the-20th-century postcard from the Shuman collection. This one is at the intersection of West Grace Street and Allen Avenue.

Greenery

Whether 10 feet or 25, the land between the front porch and the sidewalk is — in the best streetcar suburbs — a small oasis of green, Smither says.

And, importantly, it’s less a yard and more a garden.

“In front of the porches there’s street trees and all these small front gardens,” he says. “So instead of having a lawn in front of your house, you’ve got these groundcover shrubs and small flowering trees.”

This, Smither says, is an example of biophilia — our tendency as humans to want to connect with nature and living things (the term was coined in the 1980s by Harvard biologist and naturalist Edward O. Wilson).

In small urban settings, biophilia is an exercise in creativity — tomato vines and herb gardens growing on balconies, for example. In streetcar suburbs, which have a little more room, biophilia takes center stage in front of homes.

“You’ve got a lot of different textures going on that make it very interesting,” Smither says of the front gardens. “Now, it’s not like the James River running down the street, but it definitely has a lot of variety of plant material.”

An overhead view (via Google Maps) of the Fan. From overhead, the smaller parks (circled in red at North Meadow Street, North Lombardy Street and North Harrison Street) look like pennants pointing to 7.5-acre Monroe Park.

Parks and plazas

A natural extension of the biophilia idea, small public parks (and sometimes plazas) are some of the most important spots in denser neighborhoods, Smither says.

Some of his favorite local examples are in the Fan, where the aptly named Park Avenue cuts diagonally from Arthur Ashe Boulevard to North Laurel Street, creating a series of small triangle parks at North Meadow Street, North Lombardy Street and North Harrison Street (in front of VCU’s Singleton Center for the Performing Arts).

“And if you keep [going] east, that line goes through the Compass and runs all the way down into Monroe Park,” Smither says. “So there’s a large park and then there are these small triangular pocket parks that are a great scale for the neighborhood.”

From overhead, the smaller parks look like pennants pointing to 7.5-acre Monroe Park on the eastern edge of the Fan. The pocket parks exist because of the Fan’s geometry, Smither says. (The neighborhood narrows from west to east, causing streets to converge.)

“And what I like about, let’s say, Lombardy Street Park and Meadow Street Park is there are buildings around the whole edge of the park,” Smither says, “and you have porches, balconies, windows, and doorways that face directly onto the space.”