Arts & Culture

A bird’s-eye view

Scientific illustrator Nick Garnhart (B.F.A.’22) reflects on how they use art to teach — and learn — about nature

When I interviewed Lesley Bulluck, Ph.D., and Catherine Viverette, Ph.D. (M.S.’04, Ph.D.’16), about their work on the prothonotary warbler (“A bird call for wetland health,” summer 2024), I asked if they knew an artist who could create an accompanying illustration. The researchers enthusiastically recommended Nick Garnhart (B.F.A.’22).

“Nick took my class, and they did an amazing map on bird distribution along a river,” Bulluck says. “They illustrated all the species on the map.”

Garnhart wasn’t supposed to take Bulluck’s avian ecology course; they hadn’t taken the prerequisites. But the self-described “bird nerd” had met Bulluck while working on a project with another professor and mentioned they wanted to learn more about ornithology.

Bulluck let Garnhart take the course as an independent study and create a documentary video and illustrations in lieu of an analytical project.

“I was so incredibly grateful Lesley took a chance on letting me in her class,” Garnhart says. “This is cheesy, but it changed my life. It helped me figure out what I wanted to do with science and how I wanted to be engaged in it.”

Garnhart now works as a bird research technician and scientific illustrator for Virginia Working Landscapes, a program of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. They shared with me their approach to illustrating nature.

Nick Garnhart (B.F.A.’22)

Did you know when you started at VCU that you wanted to be a scientific illustrator?

When I was in high school, I was 95% sure I wanted to do art and environmental science. And then, in my first year at VCU, I went into communication arts [a VCUarts department that offers classes such as figure drawing, digital drawing, storyboarding, comics and book cover design].

I was also pursuing a major in art education, but then I took an intro to biology class as a general education requirement, and I was like, “Oh, man, I forgot how much I love science.” I knew I had to switch. I kept my major in communication arts and ended up doing a minor in environmental science. I was curious about how learning the scientific side of nature could help inform my art as well as help me become a better naturalist and biologist.

What drew you to communication arts?

I originally wanted to do concept design for movies and animation. Concept design is used for pretty much every fictional production. A producer will say, “I want a character that has these characteristics,” and then you draw several different versions. You’re basically bringing to life what they have in their mind, but you’re also making it your own.

Does that background in concept design inform your scientific work?

With scientific illustration, there is definitely a range. There’s medical illustration, where you have to be extremely precise. And there’s naturalist art [art depicting nature], where you can be a little bit more loose with your interpretation. And then maybe a middle ground could be drawing a field guide where you want things to be identifiable, but it doesn’t have to be to the millimeter, like with a medical illustration.

I feel like with those more naturalist things — like what I did for you for this article — I really get to mix my earlier experience in concept design with scientific illustration and environmental education because I can draw the environment how I want it to look. I can create a scene using scientific information.

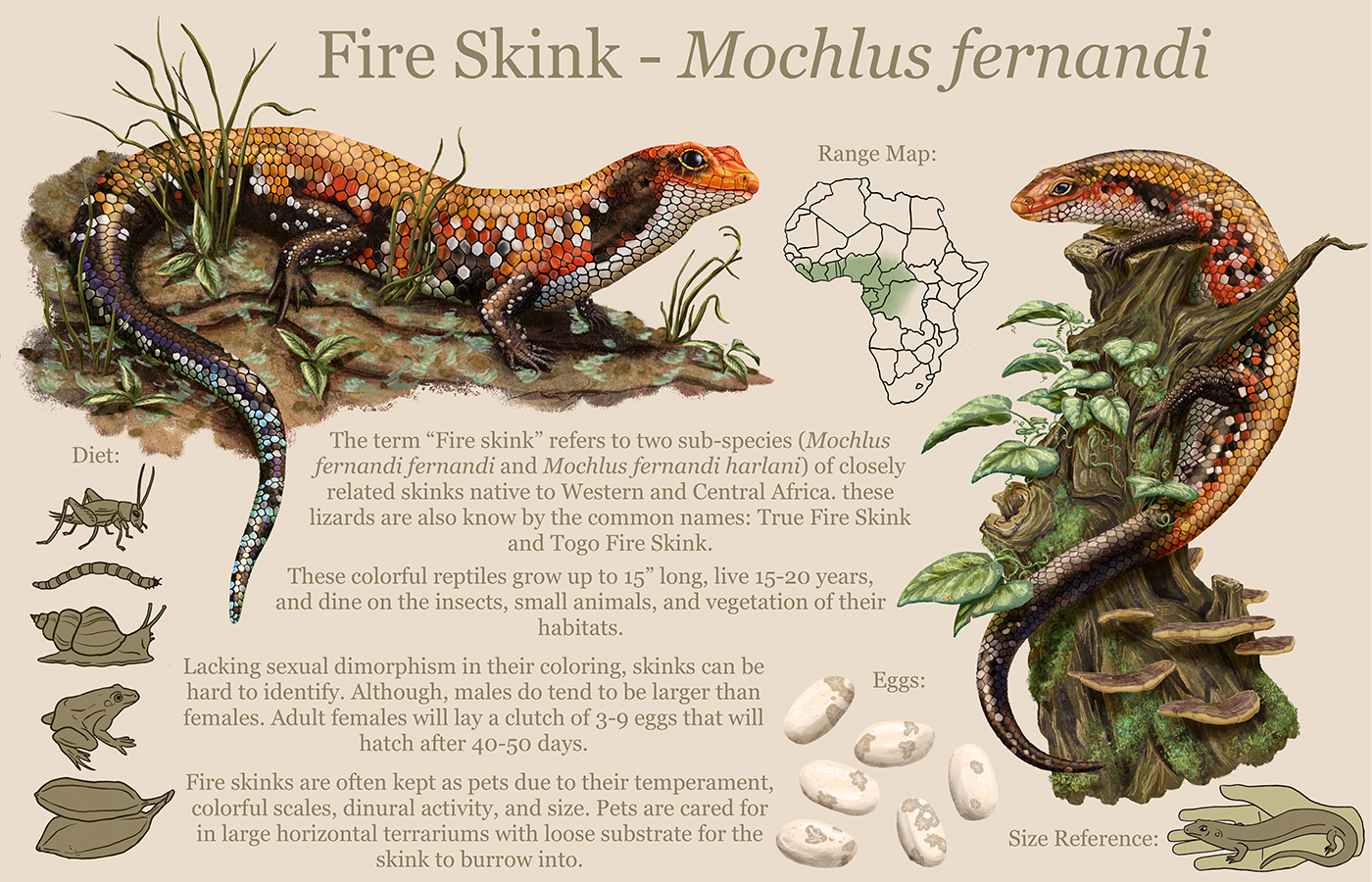

This African Fire Skink infographic is an example of the detail required in a classic scientific illustration.

What scene did you want to create with the warbler illustration?

I wanted to depict the birds singing and feeding, two behaviors they engage in when they are at their breeding grounds, and also show Lesley and Cathy canoeing underneath. I wanted to show the bird’s habitat — a wooded swamp — so I drew a swamp oak, and then I drew wasp galls on the oak leaves because I didn’t want to just show a static environment. The illustration doesn’t just depict a bird in a tree; it’s so much more. Viewers can connect to it more if it’s accurate, but I can still be creative while being accurate.

You’re already starting to answer my next question: Centuries ago, artists traveled with explorers to illustrate the flora and fauna. Now, everyone has easy access to a camera and can photograph anything in nature. What does a scientific illustrator offer that a camera can’t?

If we look at the illustration I did for you, there’s no way that I could photograph a bird singing next to a bird feeding its babies with Lesley and Catherine canoeing under it. With an illustration, I can make it my own. I can depict something that cannot be photographed.

If I’m illustrating a plant, I can show the bloom at the same time as the seed head at the same time as the bud. You’re not going to find a plant that has the bud, the flower and the seed head all at the same time. But I can do that in an illustration.

I’ve done several illustrations where you can see the ground — the inside soil structure — as well as what’s on top. You can dig a hole and take a picture showing the grass and the dirt, but it’s not the same. You can’t also show the wildlife under the ground.

And there are so many things that cannot be photographed that are really important. Maybe something is really elusive and no one has taken a photo of it, or no one has taken a photo of it from a certain angle or demonstrated behaviors that are happening next to each other at the same time. There are so many uses for illustration that just can’t be replicated with a camera.

I would imagine this work helps you get to know a plant or animal really well because you have to study it so closely.

Definitely.

Last year I did a personal project where I was drawing native wildflowers of eastern North America. I’m kind of a baby botanist; I don’t know a lot of plants, but I am trying to learn more. When I’m drawing a plant, I’m looking at tons of photos of it, and I start to subconsciously say, this leaf has five leaves, and those leaves branch off into three points. I’m slowly getting it in my head because I’ve seen so many pictures and need to draw it accurately.

For that project, I drew a white turtlehead, and then later I was out in a grassland and I found it. I knew what it was because I had drawn it, and I wouldn’t have known otherwise.

I did a lot of research for the prothonotary warbler illustration. I knew quite a bit about prothonotary warblers because I was Lesley’s student. But I didn’t know everything. I was looking up answers to questions like: What is their broad habitat? What does that habitat look like? What kind of plants are growing there? What is interacting with those plants?

I asked Lesley to send me some of her photos of the warbler. I have another bird mentor in my life, Bernadette Rigley [a doctoral research fellow with VIrginia Working Landscapes], and I had her send me photos that she had taken. I also searched Google and iNaturalist [a database of wildlife photos]. I think I had at least 80 photos of the bird and then the same amount for the habitat and the trees.

The illustration of the newt [top photo] is one that I created based on a photo I had taken. The only time I’ll copy a photo is if I’ve taken the photo.

But even then I got to say, “Well, I don’t really like how the tail was shaped in the photo that I took.” I used a different photo I took to change the tail.

When I was making that illustration, I learned more about the physiology of the newt. When I was holding it, I wasn’t counting its toes. I was thinking, “I’m not aware of how many toes you have because you’re just cute, and I’m just looking at you.”

You also make art that’s more fantastical. Is that a good break from your daily work?

Oh, yeah, absolutely. Sometimes after a project that is focusing more on accuracy and science knowledge, I love to decompress by drawing a monster in the woods.

Last year I was working on several scientific projects, and I had driven by a farm at night, and there were sheep out in the farm. It was really creepy because you could see the reflection in their eyes, and I was like, “What if I drew a ghost sheep farm?” So I did, and it was a fun way to take my own observations and then make it horrible and horrific.

I think it’s good practice to have boundaries, even when you’re doing something you love for work. I don’t always have to draw something science-y. I can also draw a spooky monster.