Archives

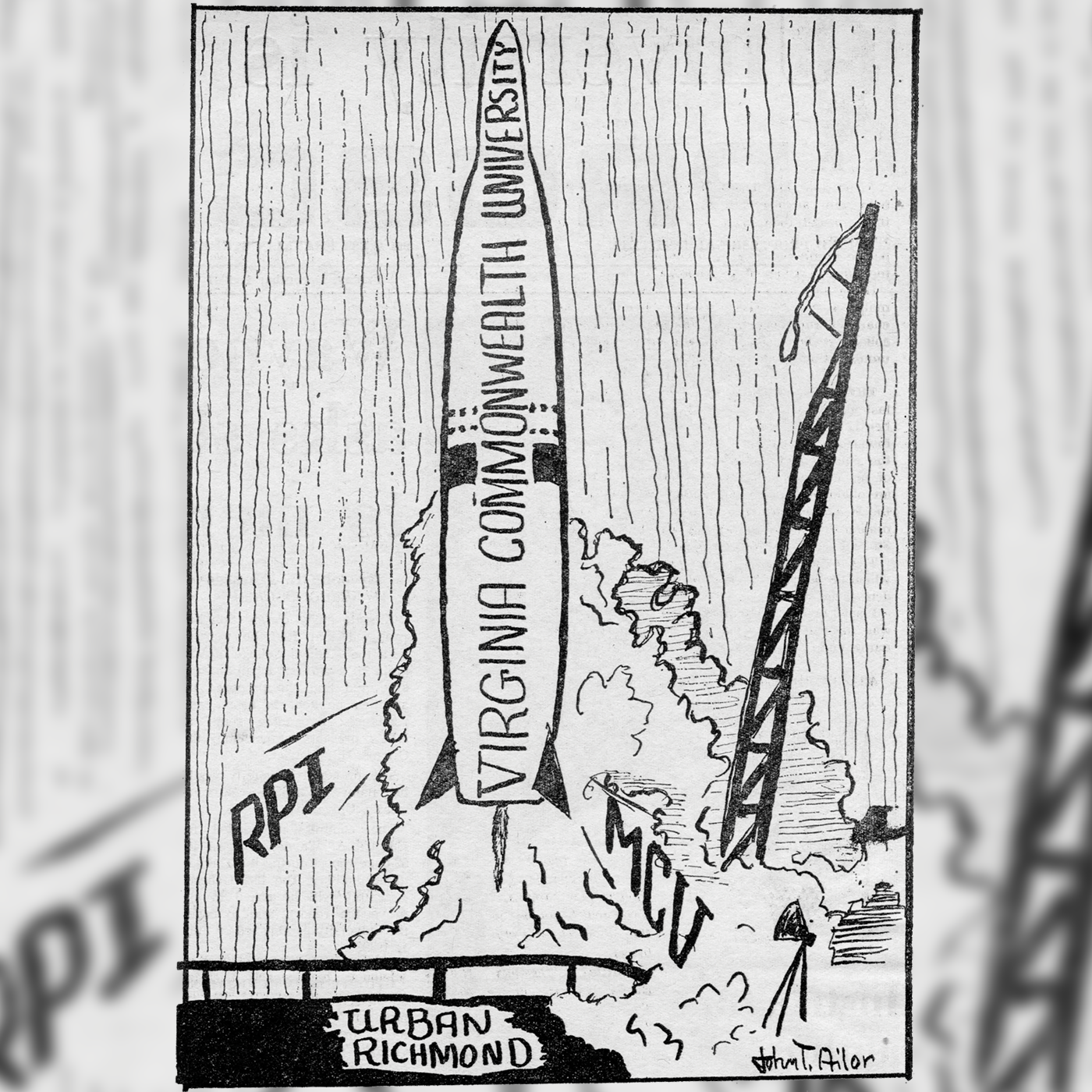

A moonshot in the arm

How RPI and MCV became VCU

It was Dec. 1, 1967, and John Edwards (B.S.’68) had left his family’s “poor, little farm” in Smithfield, Virginia, a couple of years earlier to study journalism at Richmond Professional Institute. A partial scholarship helped him pay the $400 tuition so he could take classes taught by newspaper editors and learn his trade at the student paper, Proscript.

That day, Edwards, the paper’s editor-in-chief, published an article about the Wayne Commission, a group of local bigwigs appointed by the General Assembly and led by Edward Wayne, president of Richmond’s Federal Reserve Bank, to merge RPI and the Medical College of Virginia.

The Wayne Commission didn’t come up with the idea to merge the two institutions. That was one of many decisions made by a 1965 commission to expand Virginia’s community college system and add more four-year schools, likely in response to the Higher Education Act, enacted the same year, which focused on making education more accessible.

“Neither MCV nor RPI had merger in mind,” says John Kneebone, Ph.D., a retired VCU associate history professor who co-wrote “Fulfilling the Promise: Virginia Commonwealth University and the City of Richmond, 1968-2009” with former VCU President Eugene P. Trani, Ph.D. “Each was on its own track; RPI was looking to become a proper humanities and sciences college, and the medical school was ramping up their research.”

Stories in Proscript and its successor, The Commonwealth Times (est. 1969), suggest an uneasy alliance. MCV had a more well-to-do, conservative crowd, unsure they wanted to affiliate with the stereotypical bearded, long-haired RPI student. In response to a survey, one of the nicer alums suggested the merger was like crossing a peacock and a chicken.

The new school needed a raison d’ȇtre, a mission with optimism that could float above strife, like John F. Kennedy’s call for a moon landing six years earlier.

The Wayne Commission promoted VCU’s role as an urban university, a school that could benefit from its location — “a living laboratory” — and help make the city better.

At the time, “there was a lot of enthusiasm about how so-called urban universities could really address the social problems cities were facing, that they could be a positive force for change,” says Steven Diner, Ph.D., professor at Rutgers University-Newark and author of “Universities and Their Cities: Urban Higher Education in America.”

Vice President Hubert Humphrey even made that the focus of his 1965 address at the Southern Regional Conference on Education at the Mosque (now the Altria Theater) in Richmond.

City universities, at the behest of their presidents, created urban studies departments and prioritized research on issues like poverty and crime that plagued urban areas, Diner says. They sent students into surrounding neighborhoods for community service projects. They expanded access to health care by creating clinics through their medical schools.

Until then, “urban universities had a lower-end, Kmart reputation,” Kneebone says. “The image was a school with lower standards, lower admission standards, and focused on employment rather than education.”

It was the antithesis of the still-cherished 19th-century ideal made incarnate by Thomas Jefferson 73.1 miles to the west: a university tucked away somewhere bucolic, isolated from civilization’s temptations so professors could shape and mold students’ minds.

The Wayne Commission considered a modernized version of the Jeffersonian concept with a new campus at the Elko Tract, 2,200 acres in eastern Henrico County that had remained vacant since being used as a decoy airfield during World War II.

“That was the model of the suburban off-site office park,” Kneebone says. “Stanford, in Silicon Valley, I suppose, is the best example.”

At that time, the suburbs were growing like gangbusters. From 1960-66, the population of the metropolitan Richmond area including Chesterfield, Henrico and Hanover counties grew by about 15%, even as the population of the city itself declined. Cities across the country, hurt when mostly white, middle-class residents fled desegregation, had become synonymous with decay.

Anchoring VCU in Richmond was a bold, history-shaping move that has, for the most part, aged well.

VCU has been one of the “most significant and effective institutional actors in stemming Richmond’s decline and underwriting its gradual rebound of population,” according to three University of Richmond faculty members in their recent book, “The Making of Twenty-First-Century Richmond: Politics, Policy and Governance, 1988-2016.”

Looking through that lens, the words Edwards penned in his editorial about the Wayne report seem almost prophetic: “Whether we like it or not, urbanization is coming, and the only realistic approach is to face the problems accompanying it. … Education, as has always been the case, is the answer.”

(At least Edwards thinks he wrote that. There’s no byline, and he doesn’t remember this one piece among the thousands he wrote for Proscript and his hometown paper, the Smithfield Times, which he managed for 14 years and owned for 33. “But [writing editorials] was my job as editor, and the style appears to be mine,” he says.)

“It may very well be,” the editorial continues, “the beginning of a new era — an era that finds education reaching out to learn from and to help the environment around it.”