Politics & Government

With all deliberate need

Seventy years ago, the Supreme Court ruled segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. Then the Civil Rights Movement asked its children to do their part.

A distinction, Carmen Foster, Ed.D. (B.S.’74), says, must be made between desegregation and integration if we’re going to talk about the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education and what it was like being one of the first Black kids to go to a white school.

“Desegregation is a legal process,” says Foster, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on the first Richmond city school to be desegregated and endured desegregation herself. “Integration is the social process of desegregation.”

It’s nuanced, but most Black children went through desegregation, not integration. If they had, “white school attendance” and “white school acceptance” might be interchangeable terms.

“It wasn’t like I couldn’t do the work. I didn’t feel connected,” says Foster, who in 1963 started at until-then all-white Binford Junior High, now Dogwood Middle, in Richmond’s Fan district. “People don’t want to sit beside you on the first day of school. You’ve got to figure out, How do I make friends when I’m one of the only Black kids in the classroom? It’s hard. And then, teenagers are teenagers. They do cliques. They like to mock people.

“The good thing is that Motown had come into vogue by 1964. Everybody liked The Supremes. If you knew how to do the jerk and some of the dances, they might think you’re cool, and they might be friends with you for that.”

Foster was a year and a half on May 17, 1954, when the Supreme Court released its Brown decision, ruling segregation unconstitutional 9-0. Its lesser-known companion case, Brown II, is where the court encouraged states to implement Brown “with all deliberate speed,” instructions still infamous 70 years later for their august vagueness.

The muddy phrasing allowed offending states to dally, and they fought desegregation for years, appealing in the courts with bad-faith nitpicks and procedural arcana while passing anti-desegregation laws.

“Desegregation happened on white terms in ways that damaged and unfairly burdened the Black students who went through those first waves,” says Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, Ph.D., a professor in the VCU School of Education’s Department of Educational Leadership. “We have causal evidence around the long-run impacts of school desegregation for those first Black students that went through it, to include higher earnings, better health outcomes and a greater occupational attainment — plus an intergenerational effect for their children, so that their children benefit from their [parents’] desegregation experience.

“You just have to be able to hold all of those different things in your mind and understand them all to be true: That you could get good long-term outcomes for the vast majority of Black students, even as it was implemented in ways that were deeply unfair. Just imagine what it would have looked like if segregation was implemented in ways that treated all kids on equal footing.”

Army soldiers escorted the Little Rock Nine to Central High in Arkansas when, in September 1957, they became among the first Black kids to desegregate a white school after Brown, persisting through racist mobs, National Guardsmen and the anti-federal madness of Gov. Orval Faubus.

In 1960 in New Orleans, 6-year-old Ruby Bridges joined Linda Brown (the Brown in Brown v. Board of Education) as a child face of the Civil Rights Movement when she and the Marshals Service desegregated William Frantz Elementary.

Unlike their compatriots in deeper parts of the Old South, the Black kids sent to desegregate Virginia’s schools didn’t need armed escorts. State officials went about retiring Jim Crow the way they tried to enforce it: with a facade of gentility and the appearance of paternal control.

Carmen Foster, Ed.D. (B.S.’74), was one of the Black students who desegregated a Richmond junior high school in 1963 and later wrote her doctoral dissertation on desegregation in Richmond. — Photo by Jud Froelich (M.S.’21)

Carmen Foster is a former director of VCU’s Grace E. Harris Leadership Institute and she graduated from VCU’s Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture after studying mass communications. The daughter of a Jackson Ward dentist and a stay-at-home mom (who earned a master’s degree in social work at Clark Atlanta University), Foster is descended from educators (and at least one homecoming queen) and earned her doctorate at the University of Virginia, where she occasionally teaches. She also contributes to Teachers in the Movement, UVA’s oral history project on education before and during the Civil Rights Movement.

Foster wrote her dissertation on the 1960 desegregation of Chandler Junior High School, its old building on Brookland Park Boulevard now the fifth home of Richmond Community High. Chandler was the first city school to accept Black students, and there were just two. They required no hired muscle, and the scene attracted only police and press.

“Richmond always likes to keep things neat and tidy, OK? Because they care about their public image,” says Foster, referencing the Virginia Way, an antebellum era-originating code of conduct predicated on decorous bigotry. “So the city fathers would make sure on Sept. 6, 1960, when the two Black girls, Carol Swann and Gloria Mead, went up the steps to Chandler, the headline said, ‘Everything’s normal, everything’s normal.’ Even you saw it in the [Richmond Afro-American newspaper] — ‘Everything’s normal. Everything’s gone as expected.’ What I found later when I started digging was everything was not normal.”

Following a half-decade bout of “Massive Resistance” — the statewide retaliatory movement to slow and scuttle Brown’s implementation — and nudged by the Supreme Court, Virginia finally desegregated in 1959.

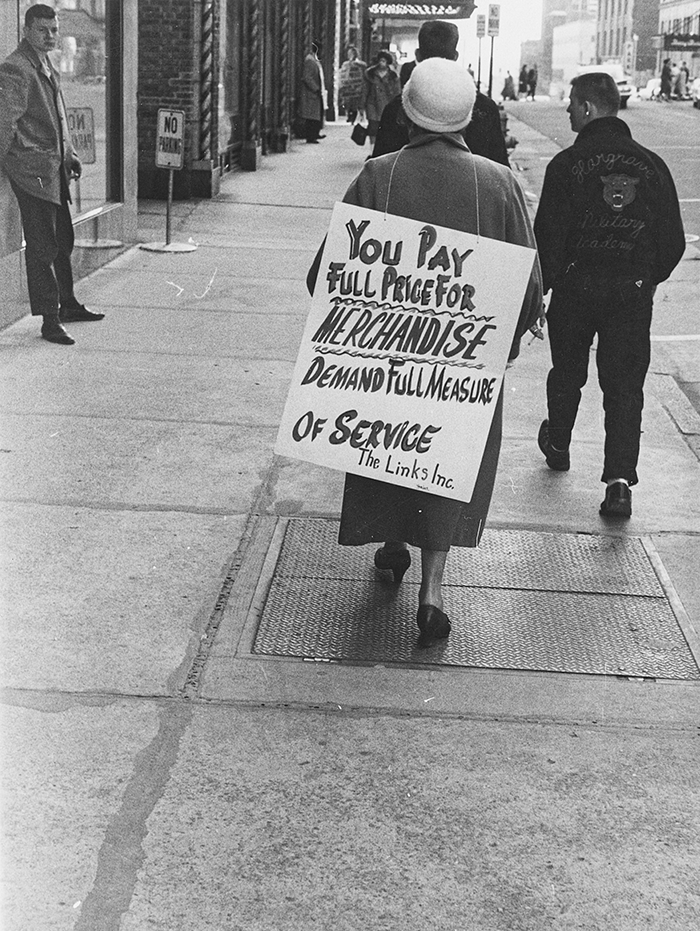

A year later, Black parents targeted Chandler as a nearby alternative to overcrowded and underfunded all-Black Benjamin Graves Junior High in Jackson Ward, doing their part to forward desegregation and support the greater Civil Rights Movement, specifically the 34 Virginia Union University students who got civilly disobedient and arrested in a downtown Richmond department store.

Inspired by the Greensboro Four’s Feb. 1, 1960, sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in North Carolina, the Richmond 34 stopped by the old Thalhimers’ Richmond Room restaurant on Feb. 22 and did the same thing. Police charged them with trespassing, and they were fined $20 each, about $200 in 2024 money.

Two days after the Thalhimers sit-in, a city school board meeting held about Chandler’s desegregation drew a hot crowd of 1,600, most of them white and annoyed that certain people wanted to attend a public school.

“You knew that there were some things that you had to do differently,” says Foster, describing day-to-day segregation in 1950s Richmond. “I just remember that my parents always insisted that I go to the bathroom before we left the house — because you know how kids are. It was because they didn’t want us to go to the colored bathroom, because they knew that they’d likely be not clean, because the store would take more effort to clean the white bathrooms than they would the colored ones. They didn’t want us to have to deal with the indignity of that.”

Francis and Dorothy Foster kept a bucket in the car, just in case.

“Our Black communities and neighborhoods were seamlessly interconnected with our segregated schools and our churches in ways where we knew those were safe places,” Foster says. “The outside world, outside the bubble, was something that we knew that was there, but children go toward where it’s safe and comfortable and where they feel valued and loved, so they’re not as eager to figure out what is that extraneous situation that’s out there beyond that. Growing up in Jackson Ward and Byrd Park, I felt loved.”

Foster describes Jackson Ward, Richmond’s famous historically Black neighborhood, as a “nurturing bronze cocoon.” It’s a term she uses for the urban Black communities that grew up after the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling established “separate but equal.” It was an 8-1 decision, with John Marshall Harlan the Elder greatly dissenting.

The affluence of Jackson Ward combined with the intellectual power of Virginia Union made Richmond a Black hub of the time, and it showed in its Black public schools. While thin on resources, they were largely run by qualified, educated people and backed by a strong middle class.

“Our teachers,” Foster says, “were primed to give us the best that they had gotten from their education, to pass it on to the next generation inside the bubble, and they loved you and they knew who your mama and daddy were and all your family, and they probably went to church with you. We had excellent teachers. We did not have resources — those were separate and unequal.”

Robert Grey Jr. (B.S.’73, H.L.D.’06) is a retired Richmond attorney and a former president of the American Bar Association and Richmond mayoral candidate. Grey, who went to VCU’s School of Business, started at Chandler in 1962 as part of another wave of desegregating Black kids, before going to the also freshly interracial John Marshall High School.

“Back then, it was just understood, ‘OK, these African American kids are going to [a formerly all-white] school. That doesn’t mean they have access to everything,’” Grey says. “It was like, ‘OK, we’ll take them into the school, but we still run everything and we will have whoever we want on these various committees and clubs and sports things, and we’ll give out some [spots] to the Black kids — but just enough so that we can say we are doing our job.’ It wasn’t like, ‘Let’s get the best talent on the floor. If they happen to be all Black, that’s the way it goes.’ Not at all. It was still a resistance to fully integrate.”

When the Civil Rights Movement asked its children to do their part, it was the parents — usually those not dependent on white people for a living — who said yes.

Grey’s mother, Barbara, is an esteemed and longtime Richmond public school teacher and administrator, and his father, Robert Sr., was an Army master sergeant stationed in France. The younger Grey spent his early years overseas.

The parents of Chandler Junior High’s two-girl desegregation force were a seafood restaurant owner and an accountant, a nurse and a pipefitter, and they wanted better resources for their kids than torn, old textbooks and broken microscopes, in crowded schools that were deliberately underfunded by white school boards. They wanted what desegregation expert Vanessa Siddle Walker, Ed.M., Ed.D., describes as “the additive model.”

“In real time, that’s not what we did,” she says in her YouTube lecture series. Walker has studied desegregation for decades and is a professor emeritus at Emory University. “In real time, what we did was an exchange model. Instead of maintaining wonderful climates [that the kids had in Black schools] and advocacy, they exchanged these for access, and it didn’t work.”

White schools also looked askance at hiring Black teachers, and with Black schools closing — those white school boards saw no reason to keep barely funding the suddenly extraneous Black schools — Black teachers largely ended up unemployed.

“Teachers were fired. Those who knew how to create these climates were fired — 50,000 or so by some estimates,” Walker says. “The [Black] advocacy networks were sacrificed as the teacher organizations were fully integrated, with agendas that were different from what [the networks] had had, and the access that they were given was never full. It was limited.”

At Binford and later Thomas Jefferson High, Foster and other Black students, assuming they wouldn’t be invited, fanned out and involved themselves in school clubs and sports. Foster joined the Future Teachers of America and a public affairs club, but “cavities” got her marked 4F for cheerleading, though she suspects it might not have actually been about her teeth.

“My father’s a dentist,” she says. “Do you see the subtlety? I’m never good enough. Let me suggest this to you: Have Black children ever had opportunities, especially during enslavement, to really do what they just wanted to do in a more entitled way? No.”

W.E.B. Du Bois was born in 1868, the first year it was completely legal for a Black person to learn to read and write in the United States, and throughout his 95 years, Du Bois evangelized and prophesized about how Black people should pursue equality through education.

In 1935, he wrote an essay for Howard University’s Journal of Negro Education, musing about the look of an integrated future. He opens the home stretch of “Does the Negro Need Separate Schools?” with a disclaimer for the rubes.

“I know that this article will forthwith be interpreted by certain illiterate ‘nitwits’ as a plea for segregated Negro schools and colleges. It is not.”

He goes on: “It is saying in plain English: that a separate Negro school, where children are treated like human beings, trained by teachers of their own race, who know what it means to be black in the year of salvation 1935, is infinitely better than making our boys and girls doormats to be spit and trampled upon and lied to by ignorant social climbers, whose sole claim to superiority is the ability to kick ‘n------’ when they are down. I say, too, that certain studies and discipline necessary to Negroes can seldom be found in white schools.”

And he predicts Brown from 19 years out: “There can be no doubt that if the Supreme Court were overwhelmed with cases where the blatant and impudent discrimination against Negro education is openly acknowledged, it would be compelled to hand down decisions which would make this discrimination impossible.”

The case’s proper name is Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, and it’s made up of five similarly souled lawsuits, the first filed in 1950 in South Carolina.

Brown as a standalone case began in 1951. The remaining three came from Delaware, Washington, D.C., and Virginia — where 75 miles west of Richmond in 1951, hundreds of Black students walked out of segregated Robert Russa Moton High in Prince Edward County, the inciting act for Virginia’s Brown contribution: Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County.

Led by 16-year-old Barbara Johns, the Moton students refused to go school for two weeks, aggrieved by overcrowding, dumpy conditions and having class in buses. Moton didn’t have a gym, cafeteria, central heat or reliable plumbing. It was built in Farmville in 1939 for 180 students. By 1951, it was serving about 450.

The Supreme Court bundled those five cases under Brown when the NAACP, desegregation’s prime legal mover behind Charles Hamilton Houston, appealed after a district court pointed 8-year-old Linda Brown in the direction of Plessy v. Ferguson. Linda’s family, one of 13 in the lawsuit, wanted her to go to the white school six blocks away instead of the Black school one mile away. The school board said no, so NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall sued.

The first successful desegregation lawsuit was Mendez v. Westminster in 1947, when a federal court, persuaded in part by a novel argument based on sociological studies that found segregation made Black kids feel inferior, said that California public schools must admit children of Mexican descent.

Marshall would reference that same sociology seven years later in his arguments for Brown, when he fronted a team of NAACP attorneys that included Richmond’s Oliver Hill. Marshall and friends argued, primarily, that separate school systems are inherently unequal, and because of that, they violated the mighty 14th Amendment’s equal protections clause.

Ratified in 1868, the 14th Amendment undergirded Reconstruction, guaranteeing rights to the formerly enslaved and banning insurrectionists from public office. Eighty-six years later it was elemental in overturning Plessy and making Brown a burly bit of government-backed racial equality.

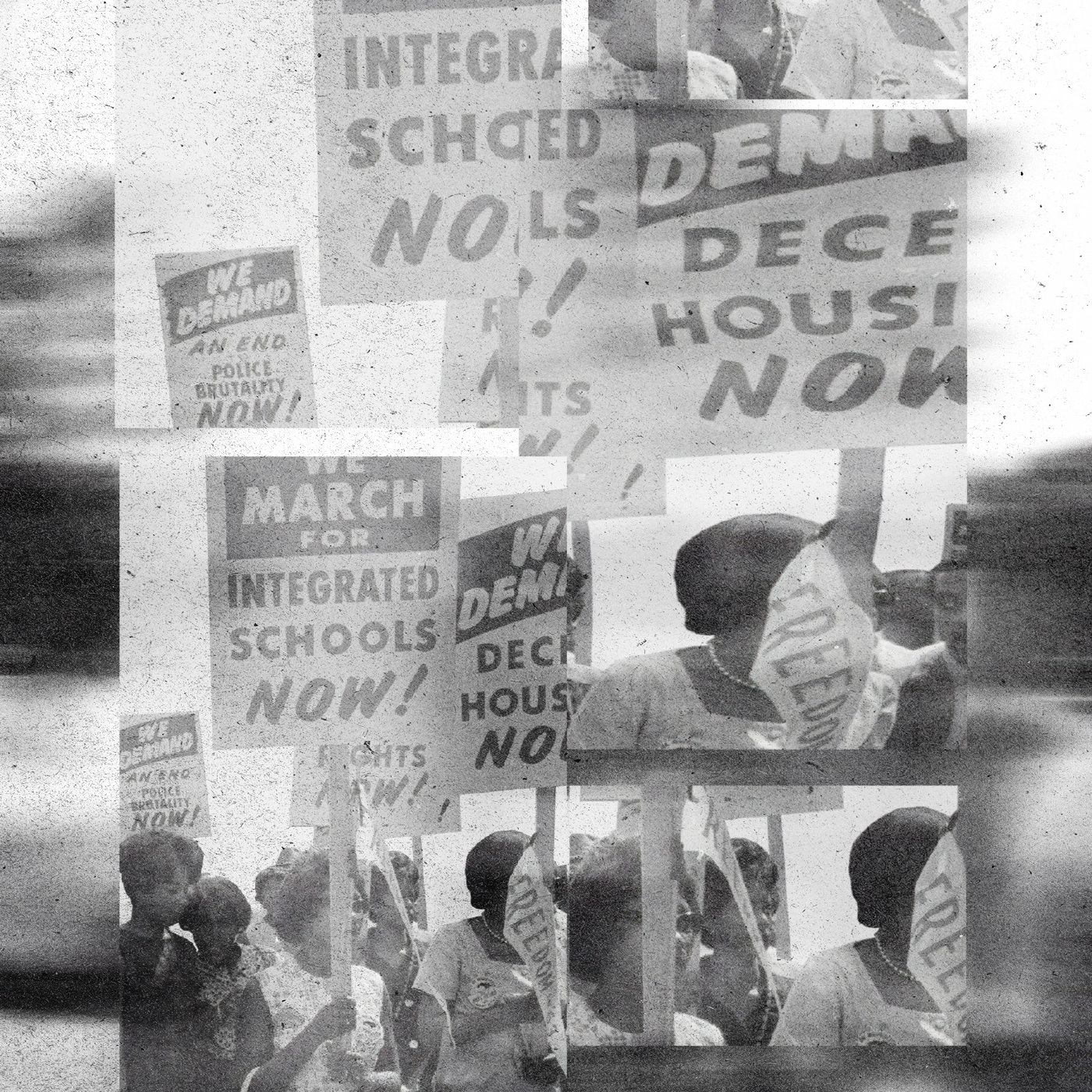

“If segregated schools are unconstitutional, how about segregated buses and segregated hospitals and segregated parks and golf courses?” says VCU history professor Brian Daugherity, Ph.D., author of three books on Brown’s implementation. “The importance of Brown v. Board of Education is not just that it leads to the breaking down of segregation within public education. I think it’s even more important because it’s the legal basis for breaking down segregation across the board.”

In 1954, 21 states either mandated or allowed segregation, including the 11 Confederate states, plus Arizona, Delaware, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, New Mexico, Oklahoma, West Virginia and Wyoming.

While the Supreme Court made segregation illegal, the nine robed ones left the small print to the states, and Virginia stalled magnificently under state political boss, Democratic Sen. Harry Byrd.

Byrd and his cohorts countered with their riff on the ol’ “states’ rights” dodge. Massive Resistance — that dodge made flesh — pressured school systems to stop any plans for desegregation and made that pressure legal with legislation in the General Assembly. They also tweaked Virginia’s constitution in 1956 to make white flight more affordable, allowing taxpayer money to be used for private school tuition. It was the primordial time of the voucher as well as a riff on the newer “school choice” dodge.

Virginia desegregated on Feb. 2, 1959, after the Supreme Court ruled Massive Resistance unconstitutional, and four Black students had their first days at Stratford Junior High in Arlington. But the Old Dominion managed to delay full desegregation into the mid-1960s. By then, federal civil rights laws, and especially 1968’s Green v. New Kent County Supreme Court case, compelled state officials to make an effort.

Unlike the Brown decision 14 years earlier, Green demanded school systems desegregate and left no room for leisurely interpretations. Green led to busing and appointed the district court as New Kent’s desegregation chaperone.

“I would say most African Americans strongly supported Brown v. Board of Education. They strongly supported integration,” Daugherity says. “It was more because they were fighting for equality in society at large. They weren’t just fighting to have their children sit next to white children in the schools. They feel integration is a route to opening up opportunities in American society at the time. Initially, there’s a lot of support for that, but as the decades go by, you see more and more hesitation on the part of African American leaders and citizens with regard to the downside or the costs of school desegregation.”

Gloria Mead (left) and Carol Swann walked with their parents to Chandler Junior High on Sept. 6, 1960. Swann and Mead were the first Black students in Richmond to attend a white school. — Richmond Times-Dispatch

According to federal data, about 90% of U.S. public school students were white in 1954 with Black students smattered through the remaining 10%.

As of 2022, 46% of public school students were white and 15% were Black (28% were Hispanic). But 60% of those Black and Hispanic kids attended schools where at least 75% of their peers were also students of color. This is not ideal.

“Being in a class where people are bringing in different lived experiences and different perspectives because of those lived experiences has really important cognitive and academic and social benefits,” says Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, the VCU educational leadership professor. “It forces students to think about something from a different perspective, and when they do that, they have more creative problem-solving, they come up with better solutions to complex problems because they’re not assuming that they automatically understand how the other people in their class discussion are thinking.

“That contact over time leads to greater willingness to live in diverse neighborhoods, to go to diverse colleges, to work in diverse workplaces, and then that has this sort of intergenerational effect, because if you pick a diverse neighborhood, you’re going to be more likely to be linked to a diverse school.”

Segregation persists, just not in such a Harry Byrdish way, and it has as much to do with money as it does race, though those things are often not unrelated. The nonprofit EdBuild, which studies school funding, found in 2019 that schools in majority nonwhite districts got $23 billion less each year than schools in majority white districts. This is a problem desegregation was meant to solve.

“There was a risk, but parents knew that their children had a lot of potential and they wanted the best for them,” says Carmen Foster, the Richmond desegregation expert. “They were hoping that being in these schools that had top-line resources would give their child an advantage. They didn’t know what was out there. You can’t predict the future. You hope that people will cooperate. What they did was a backlash. What they did was white flight. What they did was ultimately abandon the school system altogether.”

In rural areas where the student headcount couldn’t justify multiple schools, desegregation faced less subterfuge. The white and Black kids had nowhere else to go — unless, as in Prince Edward County, you just open private schools and shutter the public school system for five years, blaming low attendance. School systems in Charlottesville, Front Royal and Norfolk also closed rather than admit Black students.

It’s estimated that during the five years Prince Edward County closed its 20 or so public schools, illiteracy rates among Black people in the county ages 5 to 22 jumped from 3% to 23%, despite a great hunkering down by the Black community. Black women improvised schools in their homes, and civil rights groups set up makeshift training centers.

Enabling Prince Edward County was the Pupil Placement Board, a three-person panel invented by the General Assembly in 1956. It replaced state school boards, superintendents and parents (the Black ones) as the final say on which students went to which schools in Virginia.

Oliver Hill tussled with the PPB over desegregation in Richmond as the civil rights attorney pushed for Chandler Junior High to take Black students, even facing down the crowd of 1,600 at that February 1960 school board meeting. Foster says Hill hoped for 100 applications from Black students to attend the white school.

He got four.

And only two went.

“This is all part of a continuum. It’s part of the American saga. About struggle, you know?” Foster says. “But Frederick Douglass said, ‘Without the struggle, there can be no progress.’ And so you just understand there is struggle. For those who don’t struggle, you don’t understand progress because you feel like you’re already there. But for those who have been denied, they know how important it is to keep pushing on.”