Campus & Community

Scout law

Bankruptcy attorney Ricky Mason (B.S.’83) reflects on the most challenging case of his career: the Boy Scouts of America settlement.

The Forum is an occasional series that provides newsworthy thoughts from members of the VCU community.

Ricky Mason (B.S.’83) is an Eagle Scout, a former chair of the Boy Scouts of America’s Greater New York Councils and a bankruptcy attorney at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz in Manhattan. From 2020 to 2022, he helped guide the Boy Scouts (recently renamed Scouting America) through Chapter 11 bankruptcy, preserving the organization and creating a $2.46 billion trust for 82,000 survivors of child sex abuse.

Finalized in 2023, the trust (currently being challenged in federal appellate court) is the largest abuse settlement in U.S. history. It emerged from one of the most complex Chapter 11 cases on record, after the century-old Boy Scouts, facing a raft of abuse lawsuits, filed for bankruptcy.

Mason, a VCU College of Humanities and Sciences graduate who earned his law degree from New York University, was one of the settlement’s chief architects, forming and leading an eight-attorney pro bono committee that marshaled the BSA’s 253 independent local councils (and their thousands of employees and volunteers) through bankruptcy negotiations. He set aside nearly two years of his life for the work, emphasizing “the moral and legal necessity” of the task, he says.

In this essay, assembled from multiple interviews and Mason’s writings (both edited for length and clarity), Mason shares more about the settlement and what he learned by working on it. — VCU Magazine

Keepsakes from Ricky Mason's years in the Boy Scouts.

The Boy Scouts of America has served tens of millions of youths. In cities, towns and rural communities, its programs reinforce the core of civic life: leadership, teamwork, community engagement, concern for the environment, respect for others and self-improvement.

The BSA teaches kids to become responsible citizens.

And the BSA is fun.

Cub Scouts build small wooden cars and race them in the local Pinewood Derby. Older Scouts experience the thrill of the zipline at summer camps nationwide. And the most adventurous join and lead hundred-mile treks across the New Mexico Rockies, canoe for weeks in the isolated Boundary Waters along the Minnesota-Canadian border and sail the Caribbean from Scouting’s Florida Sea Base. In jamborees (gatherings held every few years at West Virginia’s Summit Bechtel Reserve) they meet Scouts from around the country, trade patches and stories, and learn from kids and adults similar to or much different from them.

The BSA has improved millions of lives, including mine.

But for decades, Scoutmasters, volunteers and staff sexually abused kids.

In 2020, facing hundreds of lawsuits after almost half of U.S. states changed their statute of limitation laws on child sexual abuse in recent decades, the BSA filed for bankruptcy. The lawsuits largely document abuse from the 1960s to the 1980s. The number of abuse claims dropped after the mid-1980s, when the BSA implemented new safety rules, the most important of which mandated that no adult Scout leader can be alone with a Scout.

But that does not excuse or minimize the abuse, which was devastating to tens of thousands of Scouts entrusted to the organization’s care.

The BSA filed for bankruptcy to try to compensate survivors equitably and allow the organization to continue. I believe this was the right thing to do. We owed it to survivors to take our best shot at trying to bring recognition and compensation to them, and we owed it to the current membership, leadership and volunteers to take our best shot at preserving the organization and reinforcing its youth safety culture.

“On my honor I will do my best to do my duty.” When you’re an Eagle Scout, that’s drilled into your head. At some point in your life, you’re going to have the opportunity to do that.

— Ricky Mason

Scouting helped save my life. When I was 7, my mom, Pearl, sat me down in the den of our house on West Franklin Street in Richmond. She said, “You’re a nice Jewish boy.” (This was the way she began her career discussions.) She said, “You’re going to join the troop sponsored by the synagogue like your brother. You’re going to join at age 11, and you’re going to be an Eagle Scout.”

And then she got up and left, which is the way she ended career discussions.

So at 11, I joined Troop 417 out of Richmond’s Temple Beth-El. I learned to make fires, pitch tents, elude bears, read maps, detect magnetic north, backpack, collaborate productively and be a good citizen. And when I was 14, I went to Philmont, the BSA’s 140,000-acre ranch in northeast New Mexico.

Philmont is God’s country. It’s stupendously beautiful. And though there are a lot of beautiful places in the world, it’s the experience that makes it special — getting up in the morning, packing your tent, hiking 10 miles on a trail through some mountain range or in the desert, and then being able to say, “I accomplished that.”

It’s the kind of place where you are different when you come out than when you went in.

But about a year before the Philmont trip, my mom got sick. Breast cancer. Early, it looked like she would be OK. There was a tumor and my father said the doctors were 99.9% sure that they got everything. I learned that the 1/10th of 1% can be what will kill you. I visited her in the hospital, and she underwent treatment and then she was in remission. And then it just came back with a vengeance.

I became an Eagle Scout at 14 and graduated high school in three years so my mom could see it. She died my second week at the University of Maryland.

For years, I blocked out most of my memories of her because it was just too painful at the end, so a lot of the memories that I would probably otherwise have are somewhat gone. But I remember her being very strong-willed, very funny. She had a really good, wicked sense of humor.

I finished that semester. My grade-point average was barely a 2.0. I stayed home the following spring and summer and went back to College Park the next fall. It was horrible. I dropped out and returned to Richmond. I sold shoes. I did customer service at a bank. It was spring 1979. I was 19.

My boss was driving me home one night and looked at me and said, “You’re better than this. You need to go back to school.”

I had previously taken a few classes at VCU but did not excel. I got a D in one

because I never went and just straight withdrew from the other. But I tried again in the fall of 1979, managing a conditional acceptance that limited me to 12 credits and mandated a C average.

I needed to start putting one foot in front of the other. I needed to have a goal. “What’s my goal?” My goal is to do as well as I can. My goal is to get an A in this class. “How do I get an A?” I need to study this weekend. I need to actually do the work. I need to turn in the assignments. I need to study for the tests.

I had to relearn these things — and it was sort of like learning how to get a merit badge. “How many merit badges? What do I want to do?” Well, I want to put one foot in front of the other. Eventually, I want to become an Eagle Scout. The road to Eagle Scout and the road to getting my college degree were pretty similar. And I don’t think without one I would have had the other.

I realized if I can become an Eagle Scout at 14, if I can climb Mount Baldy at Philmont, then I could do this. I met my future wife, Beth (B.S.’84), in freshman English — first class of the fall semester, bright and early at 8 a.m. I declared a major in economics. I had a 4.0 except for a B+ in biology lab. (Beth occasionally still reminds me that she did better in that class.)

I carried those Scouting lessons with me when I graduated from VCU and went to law school. I carried them with me when I joined the volunteer board of the BSA’s Greater New York Councils in 2008. I carried them with me in 2015 when I voted — along with two dozen fellow board members — to hire the nation’s first openly gay adult Scout leader. And I carried them with me when the Boy Scouts filed for bankruptcy.

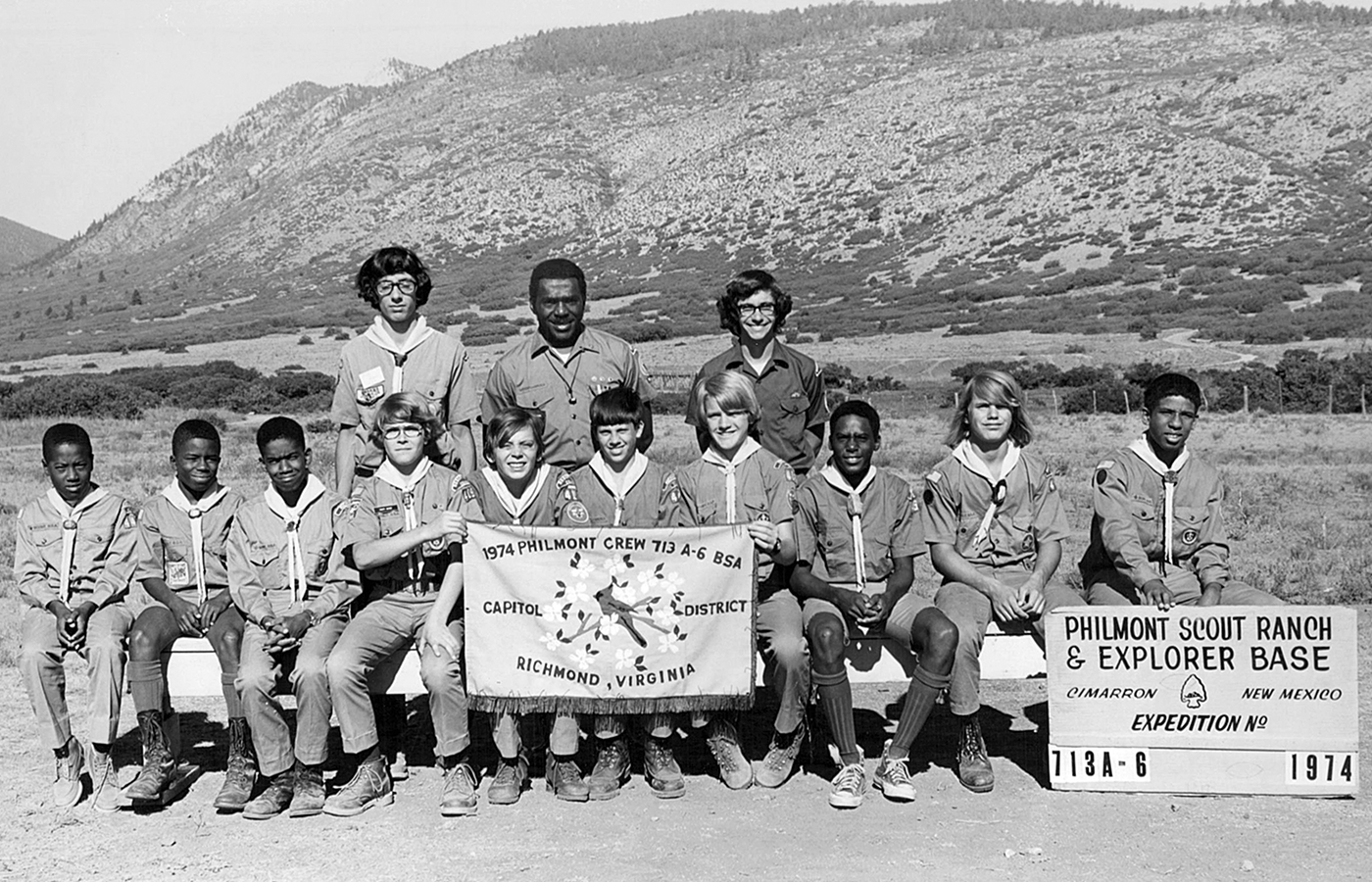

Ricky Mason (back left) at Philmont Scout Ranch in 1974, the summer before he made Eagle Scout. (Courtesy of Ricky Mason)

The first lines of the Scout Oath are “On my honor I will do my best to do my duty.” When you’re an Eagle Scout, that’s drilled into your head. At some point in your life, you’re going to have the opportunity to do that. The Boy Scouts bankruptcy case was my opportunity.

This was one of the most complex Chapter 11 cases ever. The BSA is huge — a national organization chartered by Congress with 253 independent local councils, each a nonprofit governed by its own volunteer board and with its own finances. The councils organize the Scout troops and administer Scouting programs in their jurisdictions across the country, under charters from the national BSA. Without the local councils, the Boy Scouts of America cannot survive.

Only the BSA itself filed for bankruptcy. Keeping the local councils out of bankruptcy was critical because the BSA needed them to survive and help fund the trust. And participation had to be unanimous to bring in the most dollars for survivors. The councils together contributed nearly $700 million. The national BSA and some of its insurers and troop sponsors contributed the rest.

As chief counsel for the local councils and as chair of their representative committee, I led a three-year effort that required all our collective skill and experience. We had to convince over 10,000 local council board members of the moral and legal necessity of using resources not to support youth today but to resolve abuse claims, lest the organization they loved collapse. And we spent countless hours in discussions with representatives of the survivors.

Those negotiations were some of the most intense I’ve had in my life. Without a fantastic team, both in my law firm as well as the local councils on the committee and across the country and in the national Boy Scouts organization, and without the support of my family, this all would have failed. That it didn’t is, I think, a testament to the Scouting movement, to the survivors who came forward and to their attorneys, who were skilled and passionate advocates on their clients’ behalf.

The result: the largest abuse settlement in U.S. history, $2.46 billion, and a framework for enhanced youth protection in Scouting, created in partnership with survivors. Those protections include hiring an experienced senior executive in charge of youth protection who works with a committee of survivors and Scout volunteers.

I was honored to help construct the BSA settlement and believe it should serve as a model for how to confront and reconcile difficult issues in our society. In the Boy Scouts case, you had deeply felt emotions. Over a million kids and thousands of volunteers are in Scouting today and many people, including me, believe strongly in the good that the organization does. But for survivors, they were abused in their years in Scouting. It’s horrifying what happened to them. And there really aren’t enough words in the English language to describe it because each word you say feels insufficient. Having that damage and injury is well beyond awful.

So how do we reconcile with the past and try to address it? It begins by making an effort, by being respectful, and by acknowledging where people are, how they feel and what they believe.

That may not be cookbook-ready, but it’s at least a mindset that gives you a chance for a resolution. During the Boy Scouts settlement, the process to get to that mindset — and then try to figure out how to create something broadly acceptable — was the challenge of a lifetime. We owed it to everyone to make that effort, to take our best shot at making this right.