Arts & Culture

‘Ain’t nothing like the real thing’

Scott Nolley (B.A.’91) followed his love for art and science to a dream career as an art conservator. More than 30 years later, he reflects on the rewards of bringing a work of art back to its former glory and the responsibility of being part of its lineage.

“I’m very attached to that sculpture.” — Scott Nolley

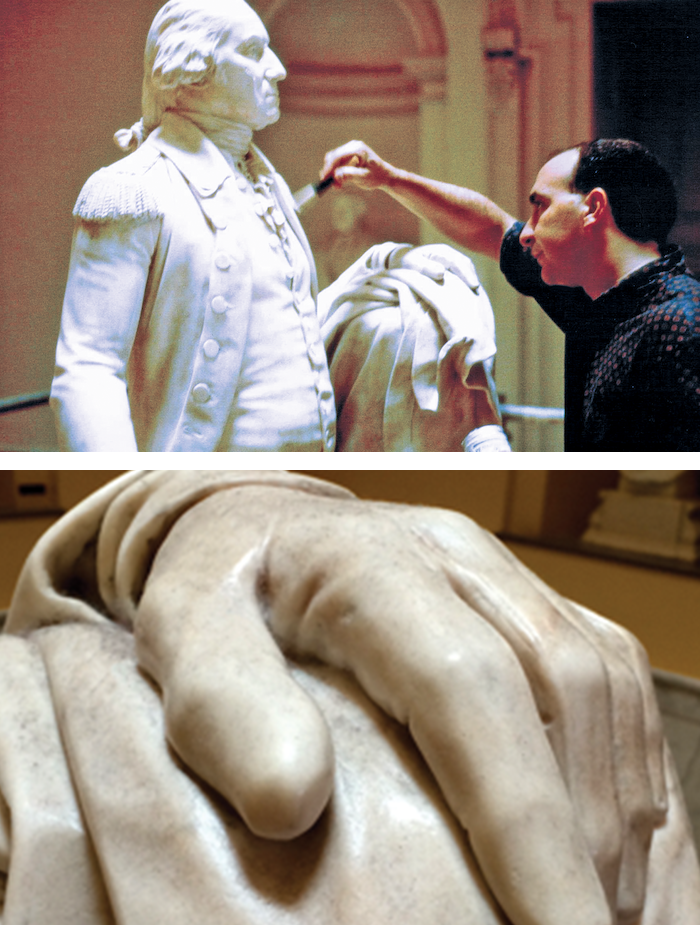

In the early 2000s, art conservator Scott Nolley (B.A.’91) was asked to restore the late-18th century marble sculpture of George Washington that lives in the Virginia State Capitol rotunda. At the time, Nolley worked in private practice and as conservator of objects and paintings for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The sculpture, commissioned by Virginia legislators in 1784 and created by renowned French artist Jean-Antoine Houdon, is considered the most accurate portrayal of the Revolutionary War hero. Houdon sailed for almost two months to Philadelphia and then traveled to Mount Vernon, where he spent two weeks with the future first president. He took a plaster cast of Washington’s face, captured detailed measurements of his body and created a terra-cotta model of his head and shoulders. Houdon returned home and spent six years creating one of the only likenesses of Washington taken from life. It was installed in the Capitol in 1796.

Houdon’s masterpiece had a rough 200 years. Before touching the sculpture, Nolley searched through old newspapers on microfilm and discovered that an 1866 gunfight between three newspaper editors had damaged Washington’s cane and its tassel. He learned that a slew of plaster casts had been taken to cast bronze copies of the sculpture in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He learned from a 1930s article that the sculpture was cleaned regularly with water and lye soap. Those wet cleanings seem to have continued until the early 1970s, when the sculpture was coated in a mix of turpentine and beeswax, then a common restoration treatment.

All this well-meaning attention damaged the statue. A restorer had at some point repaired the cane and tassel, but the repairs had gone off color and needed to be toned. The molds caused stains and cracks and left ingrained plaster as residue. The water-based cleanings had made the marble “sugar” — the polished surface, in other words, had started to dissolve, appearing as powdery granules, obscuring the fine details Houdon was known for. The turpentine and beeswax coatings had yellowed, becoming darkened with trapped dirt and grime.

Nolley and a small team removed the turpentine and beeswax coatings and cleaned the sculpture with a customized mix of solvents and detergents that wouldn’t damage the surface. They coated it in refined clay to draw out the stains.

In a happy twist of fate, the early cleaners, armed with their lye soap, had neglected to clean behind the founding father’s ears. In this one instance (unlike in 1950s sitcoms), that was the right thing to do because it enabled Nolley to assess the sculpture’s original sheen.

Nolley color-corrected the cane and tassel with dry pigments in an acrylic binder so they would blend in, removed the plaster and filled in the cracks that were disfiguring. He applied several light coatings of microcrystalline wax to the surface, which, unlike turpentine and beeswax, has high standards of purity, is clear and dries hard. This allowed Nolley to control the wax’s gloss and match the luster he saw behind the ears.

“On a microscopic level, the wax is filling in those spaces between the individual grains of marble and restoring that integrity, which at the same time restores the optic effect because there’s a certain play of light that marble is known for,” Nolley says. “The light goes in and bangs around in the marble and comes back to the viewer, giving it some sense of life.”

After three light applications of wax, “Houdon’s genius was apparent,” Nolley says. “It was like developing a photograph.”

“Washington is portrayed wearing a wool jacket. How [did Houdon] get the appearance of wool in marble? And those gloves. You can see his knuckles through the tense, tan goatskin and the individual stitches around each finger that were restored with the application of the wax.”

Nolley felt like he was seeing Washington come to life. “You feel responsible,” he says. “All of a sudden he’s yours.”

“It’s amazing how little it takes to sort of throw an object off of its purpose.”

Today, Nolley is head conservator at the Smithsonian Institution’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. Most weekday mornings, he’s in a cavernous lab with exposed pipes and a wall of windows covered by UV screens that protect the artworks resting on easels and tables.

Other days, he travels to one of a handful of the institution’s off-site storage facilities the Hirshhorn shares with 20 other Smithsonian museums. Nolley’s a bit vague about how many there are — it’s not clear whether that’s because the general public isn’t meant to know or because he himself isn’t quite sure.

“Picture the last scene of Indiana Jones and the ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark,’” Nolley says, referring to the moment when a crate housing the Ark of the Covenant is wheeled into a huge warehouse with similar crates stacked floor to ceiling. According to legend, that space was modeled after a Smithsonian storage building. The Hirshhorn alone has more than 13,000 objects in its permanent collection — “lifetimes of work,” Nolley says.

He rarely twiddles his thumbs.

Nolley oversees three other conservators who care for sculpture, works on paper and time-based media (including video and audio), respectively; he focuses on the paintings. Sometimes, he evaluates requests from other museums to borrow artwork for a special exhibit. He considers a range of factors, like the other institution’s security and climate control and whether the object can travel without damage. At any given time, a few hundred Hirshhorn objects are on loan.

Other times, he’s restoring artworks for in-house exhibits, like “Revolutions: Art from the Hirshhorn Collection, 1860-1960,” on view through April 20.

“Revolutions” took years of behind-the-scenes research, planning and manual labor. Nolley inspected the exhibit’s 200-plus objects and, when necessary, cleaned and restored them. There’s no mention of him in the gallery labels or press materials, but it’s Nolley who decided what an object needed and Nolley who performed the treatments, knowing a mistake could damage — or even ruin — something irreplaceable.

Art conservation is not for the lily-livered.

“Scott has to be a translator whose first requirement is to have an in-depth understanding of the work at hand,” says Elizabeth King, a sculptor and VCU School of the Arts professor emeritus whose work is in the Hirshhorn’s permanent collection. “He also has to understand the body of work from which it comes and even the historical moment from which it comes.”

Sargent’s 71 5/8” by 45 3/4” portrait of Kate A. Moore, a Pittsburgh socialite who hosted American expatriates in Paris, greets visitors as they enter the Hirshhorn’s “Revolutions” exhibition. — Photo by Jud Froelich (M.S.’21)

One of the works Nolley cleaned for the exhibit was John Singer Sargent’s “Mrs. Kate A. Moore” (1884), which had been exposed to cigarette smoke when it hung in one of the lavish homes of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, the museum’s namesake and original benefactor. (Hirshhorn and his wife, Olga, had homes in all the enviable places, including D.C., New York, Connecticut, Florida, California and the French Riviera.)

Secondhand smoke can leave a yellowy, gunky film, Nolley says, which makes the painting “lose the crispness — that range of contrasts between the blacks and whites.” He cleaned it, dabbing on a homemade solvent with a large Q-Tip-like instrument to bring back the sumptuous contrasts that help transform the portrait from a mere likeness to an expression of the sitter’s spirit.

Another work in the show, Piet Mondrian’s 1935 painting, “Composition with Blue and Yellow,” has impossibly straight, hand-drawn intersecting black lines on a painted white background. The only areas of color are a small blue rectangle in the bottom right quadrant and a large yellow square in the top left corner.

When Nolley assessed the painting, he saw cracks along its edges from when the canvas had been pulled taut across the stretcher at some point in its history. In the art world, that’s called re-tensioning, and it has to be done periodically because canvas loosens over time. Nolley had to fill in those cracks, “color-matching across the original artwork into those areas of repair,” he says.

There were also cracks in the tissue-thin layers of yellow paint that were “so full of dirt and grime that there were these sort of lightning bolts of black across the surface of the picture,” Nolley says.

Cracking is inevitable in oil paintings because the paint layers expand and contract in response to temperature and humidity changes. A conservator has to decide with each painting whether a repair is appropriate.

“When the cracks become disfiguring in relation to this solid square of white, when the square is populated with fissures, it doesn’t serve the artist’s intent,” Nolley says. A color-block painting is hardly a color-block painting when the block of color is interrupted by grimy black lines.

Nolley points out areas of Piet Mondrian’s “Composition with Blue and Yellow” where he filled in cracks. Conservators don’t always fix cracks — they are an inevitable sign of aging — but he fixed these because they interfered with the viewer’s experience of the color-block painting. — Photo by Jud Froelich (M.S.’21)

“We’re really trying to be as imaginative as possible when it comes to creating a space that will be able to perform to the needs of artists and the landscape of creativity. And it’s a renovation of a scope that we hope will remain performative for 50, 60, 70 years.”

The Hirshhorn opened in 1974, after financier Joseph Hirshhorn gave his mammoth collection of 19th- and 20th-century painting and sculpture to the Smithsonian Institution. Hirshhorn, who was born in Latvia and immigrated to Brooklyn as a boy, wanted the works to be accessible to a broad public and liked that Secretary of the Smithsonian S. Dillon Ripley planned to create a free national museum of modern and contemporary art.

Hirshhorn initially gave more than 6,000 works of art, then bequeathed 6,000 more and endowed the museum with $5 million upon his death in 1981. He gave the board of trustees permission to deaccession (sell off) objects from his collection, as long as the proceeds were used to purchase more art.

The works are housed in a round brutalist building designed as a piece of functional, minimalist sculpture, a contrast to its classically designed neighbors along the National Mall. When the Smithsonian began breaking ground in 1969, Pulitzer-Prize winning architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote that, “It will be the biggest marble doughnut in the world.” Marble was too expensive; they ended up using concrete mixed with crushed pink granite.

It still, however, looks like a doughnut.

“Curators can strike harmony or do battle with its curved walls,” Nolley says.

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, the museum launched a $60 million renovation of its sculpture garden, scheduled to reopen in 2026. That will be followed by a renovation of the main building, led by Selldorf Architects and by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, where original architect Gordon Bunshaft was a partner. Construction timelines and budget aren’t yet public.

To prepare for the renovation, Nolley spends hours in meetings, planning the updated building’s HVAC and lighting systems, both integral to maintaining a work of art.

It’s difficult to develop the ideal conditions when designing a space for art that doesn’t yet exist, especially objects made with nontraditional media. “We’re taking our past experience of modern artists and their combinations of materials and the demands they’ve placed on the building,” Nolley says. “We’re thinking about how we might design the next iteration of the building for flexibility and performance.”

One way is to create zones with varying temperatures and humidity levels to accommodate different media. If a curator wants to display artwork made with living plants, for instance, they could do so in a more humid space, away from metal sculpture that would corrode in damp air.

These discussions are preliminary and complex as Nolley and his colleagues try to figure out how they can serve the next several generations of artists while preserving the character of the building — “an artifact unique unto itself,” he says.

Nolley leans against the fountain in the center of the Hirshhorn Museum and recalls another 1970s brutalist edifice with a courtyard. “I’ve lived lives in [VCU’s] Pollak Building,” he says, remembering an evening printmaking class he took with David Freed, VCU School of the Arts professor emeritus. “We used to bring wine and cheese to class.” — Photo by Jud Froelich (M.S.’21)

“A career in conservation is a commitment because you only get really good at it when you’ve been doing it for, like, 20 or 30 years. I’m in my prime.”

Nolley still remembers the first time he saw the lab on the top floor of VCU’s Anderson Gallery, used by students in the now long-defunct pre-conservation program. The year was 1983 (he thinks), and, about a year earlier, he’d transferred to VCU to become a music major, after studying on a premed scholarship at St. Andrew’s University, a small private school in North Carolina.

While on St. Andrew’s idyllic campus, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, he had been captivated by the sounds of a harp coming from a rehearsal room. He realized he liked the arts too much to commit to a life of pure science. After two years of premed classes, he decided to study piano and oboe (“a beast of an instrument to play”) at St. Andrew’s and then at VCU School of the Arts.

Now he was having second thoughts about that, too. He couldn’t see himself teaching high school band or performing in concert halls — common career paths for music majors. One day, he mentioned this to one of his professors, Landon Bilyeu. Bilyeu’s response? Visit the Anderson Gallery lab.

“I could close my eyes and play it like it’s a film clip,” Nolley says. “Walking through that door and seeing the scientific equipment and the paintings on easels and smelling all the solvents and the great things that characterize a painting studio, I thought, ‘Oh, this is it. This is good.’ And I literally walked across the street to the registrar’s office and changed my major.”

When Nolley started the program, he was thrilled to make art while studying the history of restoration, the behavior of materials and the ways temperature, light and humidity can affect an object. Conservation combined his two loves, the perfect fit for someone fascinated by infectious disease — Nolley still reads medical journals for fun — but so moved by the dulcet sounds of a harp that he changed his major and transferred schools.

“We would squeeze egg yolks and grind our own paints. We would walk through fabrication technology history, from cave painting to easel paintings, from decorative arts to sculpture,” Nolley says. “And there were two years of seminars where you treated works in the conservation lab. You would be assigned a painting. You would do your research, your examination report and treatment proposal, treat the artwork and then return it to the client. We were doing work for the governor’s mansion, for VMFA and for private clients.”

Anderson Gallery was Nolley’s happy place, until VCU decided to end the program in 1987. At the time, VCU had the only undergraduate pre-conservation program in the country, according to Howard Risatti, Ph.D., VCU professor emeritus of art history and former chair of the craft and material studies department. It started in the 1970s and quickly built a reputation for preparing students for competitive graduate programs. “Thirty-three percent of students in graduate programs [nationally] had gone through our program,” Risatti says.

Though the details of what happened are hazy, budget concerns and university politics seemed to have led to its demise. The students who hadn’t yet finished were able to complete their coursework and earn their degrees.

By this time, though, Nolley had been in school for seven years and was feeling burned out. He took a break from classes to run the box office at the Carpenter Center (now the Dominion Energy Center), where he could watch shows for free.

After three years, the novelty wore thin, and he went back to then VCUarts Dean Murry DePillars, Ph.D., asking if there was any way he could finish his degree.

“I was begging,” Nolley says. “I was literally slinging around bags of Snickers and going, ‘Please, dear God, let me do this.’”

They made a deal: Nolley could earn his degree if he helped clean and restore all of the Anderson lab’s still-untreated objects. “That’s what I did for the better part of a year. I would go up into the fourth floor of the gallery and turn on loud music” — Debussy, Ravel or Stravinsky — “and treat artwork,” Nolley says.

Once he earned his degree, Nolley spent about three years working with Cleo Mullins, who had helped start the pre-conservation program before leaving VCU to open Richmond Conservation Studio. There, Nolley restored objects for historic houses, private collections and universities before going to graduate school at Buffalo State, which houses one of the most prestigious graduate conservation programs in the country.

After graduating, he interned with the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. He took a job in 1996 with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and in 1998 opened his own Richmond-based studio at a repurposed school in Fulton Hill. When the building was undergoing renovation to add more apartments, a colleague reached out to tell him the Smithsonian Museum of American History needed a conservator. Nolley started working there in 2018 and then landed at the Hirshhorn four years later, eager to focus on fine arts again.

In his free time, Nolley prepares works for the eventual move to storage during the Hirshhorn’s renovation. Here, he’s cleaning Joan Mitchell’s 1962 painting, “Giboulee (Sudden Shower),” with a long Q-Tip-shaped tool dipped in a solvent. — Photo by Jud Froelich (M.S.’21)

“You’re participating in the life of the object in critical places, in a critical role, even if it’s a simple surface clean.”

Scott Nolley thinks about conservation as the act of putting a hand in still water. “When you pull it out, you want to create as few ripples as possible,” he says. Before touching an object, Nolley sometimes spends as long as a month looking at it and studying it. He’s thoughtful about how his work will affect someone conserving the piece in the future.

Mistakes, though, are inevitable, and conservators might do everything according to best practices at the time — like coat General Washington in turpentine and beeswax — only to have someone curse their technique decades later.

“It can be daunting,” Nolley says.

“But here you are, and here’s the artwork. There’s a practical situation that needs to be addressed, and you’re the one tasked with it. So you summon your experience. You summon the experience of your colleagues, and you do the best you can. That’s sort of the story of life, really.”

There’s a mid-18th century portrait by society painter John Wollaston that took Nolley even longer to restore than the Houdon sculpture, in part because earlier conservators had created too many ripples.

The portrait belongs to the Wilton House Museum in Richmond and portrays Ryland Randolph, cousin of original Wilton owner William Randolph III. It sat for years awaiting treatment. Nolley saw it several times — when he was at VCU, when he was apprenticing with Cleo Mullins and when he was working at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. “It was shipped and shuffled around Richmond for 15 to 20 years before someone could take a deep dive,” Nolley says. In 2003, he was that someone.

Because Nolley knew Wollaston’s work, he could look at the portrait and recognize that parts had been repainted. “It looked like a bad copy of something,” he says. He could see the repainting style of the 1920s and the kinds of pigments used in the 1950s. X-rays and cross-sectional analyses revealed areas of loss in the original painting, lots of small repainted patches and at least two full repaintings.

The areas where original paint was lost were small. The repainting? Not so much. “What had happened over the years was the address of these little damages — a brushstroke of oil paint by somebody who thought they could just make it go away — and then it would go off color over time, and somebody would go back over it again,” Nolley says. “It escalated to a state where the original portrait image was buried underneath all of this paint.”

Today, conservators use a tiny brush the size of a ballpoint pen to repaint only the areas of loss, but that wasn’t always the case.

There was a saving grace, though: At some point early in the painting’s history, someone had used a water-based adhesive to attach a second canvas to the back, but they didn’t clean the animal-hide glue that had seeped through the cracks onto the face of the

painting.

The adhesive residue provided a barrier between the original painting and the repainting, preserving Wollaston’s brushstrokes and enabling Nolley to remove only the added oil paint and restoration materials.

The difference was striking.

“It took 3 1/2 years to finish,” he says. “Not to be anthropomorphic about it, but you walk in every day, and you’re like ‘Hey, Ryland.’ You commit to these projects and you become part of their timeline.”

Has there been a more stunning before/after transformation than this John Wollaston portrait of Ryland Randolph? Thanks to Scott Nolley’s expertise and skill, the painting previously kept in a closet is now showcased in the Wilton House dining room. — Photo courtesy of Scott Nolley

Nolley’s recountings — of Houdon’s Washington sculpture (“All of a sudden he’s yours”) and the Randolph portrait — bring to mind the legend of Pygmalion, who carved an ivory statue of his ideal woman and fell in love with her. In the perfect wish fulfillment plotline, Venus, the goddess of love, brought her to life.

Is Nolley the Venus in these scenarios? Perhaps. Or he could be an emergency physician, bringing life back to great art. Or maybe he’s a cosmetic dermatologist, applying mud masks and other specially developed solutions to fight “a gargantuan effort against a formidable foe” — time.

Ultimately, art conservation is a dance that requires “a delicate balance,” Nolley says. A good conservator is both committed and humble, analytical and intuitive, able to work in harmony with the artist’s intent.

“With a lot of the restorations, like the Ryland Randolph portrait, somebody thought their work would be better than the original and just repainted the whole thing,” Nolley says. “You want to be respectful, you want to be reverent, you don’t want to exercise ego.”

He describes a balloon making its way through a crowd, getting tapped by one person and then another.

“The conservator’s role in the life of an object is a single tap to get it to the next place, to get it to the next person, representative of what it was when it left your hand.”