Archives

A streetcar undesired

The life and death of Richmond’s pioneering electric street railway

Richmond, birthplace of the world’s first electric streetcar system, was once the epicenter of public transportation. But 75 years ago, amid the automobile’s increasing popularity, the city’s history-making trolleys were infamously pink-slipped and burned.

With help from experts in urban planning and U.S. transportation history and archivists at VCU’s James Branch Cabell Library, The Valentine museum, the New York Public Library and the Richmond Times-Dispatch, we revisited one of the River City’s most notable inventions — and its demise.

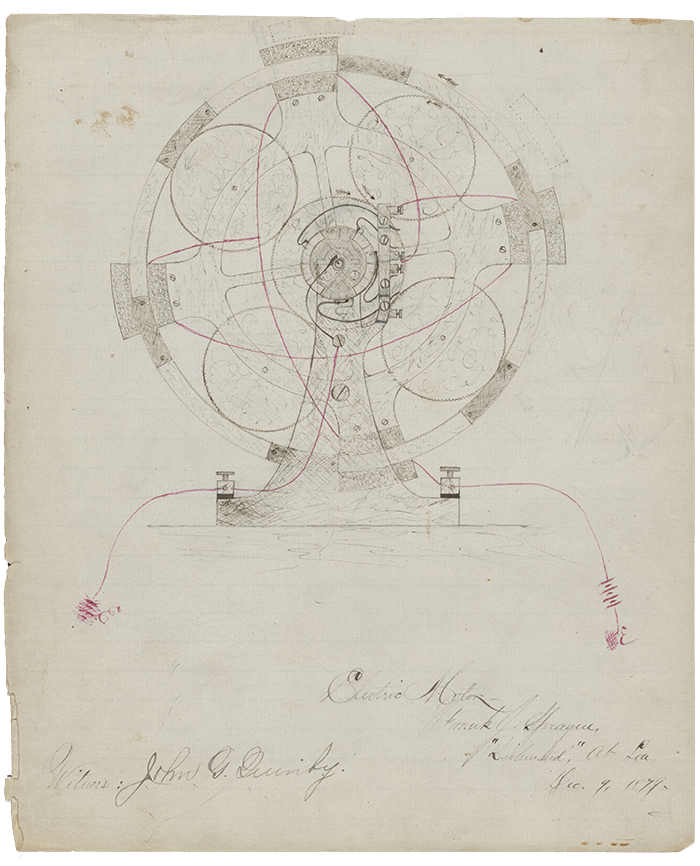

An 1879 sketch of an electric motor from Frank Sprague's inventions notebook. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

‘His is the only true motor’

The Virginia capital owes its place in streetcar lore to Frank Julian Sprague — and the U.S. Navy’s shore leave policy.

In 1882, while on liberty in London, Sprague, a 24-year-old engineer, rode the Underground for the first time. The world’s first subway, “the Tube” had one major design flaw: It was powered by smoke-belching steam engines.

“Sprague thinks to himself, ‘There’s got to be a better way to do this.’ And he starts sketching, figuring out whether there’s a way to invent an electric motor and attach it to a train car,” says Doug Most, author of “The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America’s First Subway.”

In a time of horse-pulled trolleys, soot-spewing locomotives, cable cars and experimental batteries, Sprague’s idea — a motorized railcar powered by electrified overhead wires — had revolutionary potential. Two years after riding the Tube, he left a job at Thomas Edison’s lab and unveiled his motor at a big exhibition in Philadelphia. Able to maintain speed regardless of the weight it carried, it impressed even the Menlo Park wizard. “His is the only true motor,” Edison proclaimed.

Sprague, though, needed a client. In 1887, running out of money and growing desperate, he was asked to build an electric streetcar system by the Richmond Union Passenger Railway Co. But the city’s hills were a gamble for the motor. And the contract was absurd: 12 miles of track, a power plant, overhead lines, 80 motors, 40 railcars and no payment until the job was done.

“He assumes the entire risk. It’s crazy,” Most says. “Of the 40 cars, 30 had to be able to operate at the same time. No one would take that contract in their right mind. But he had nothing else.”

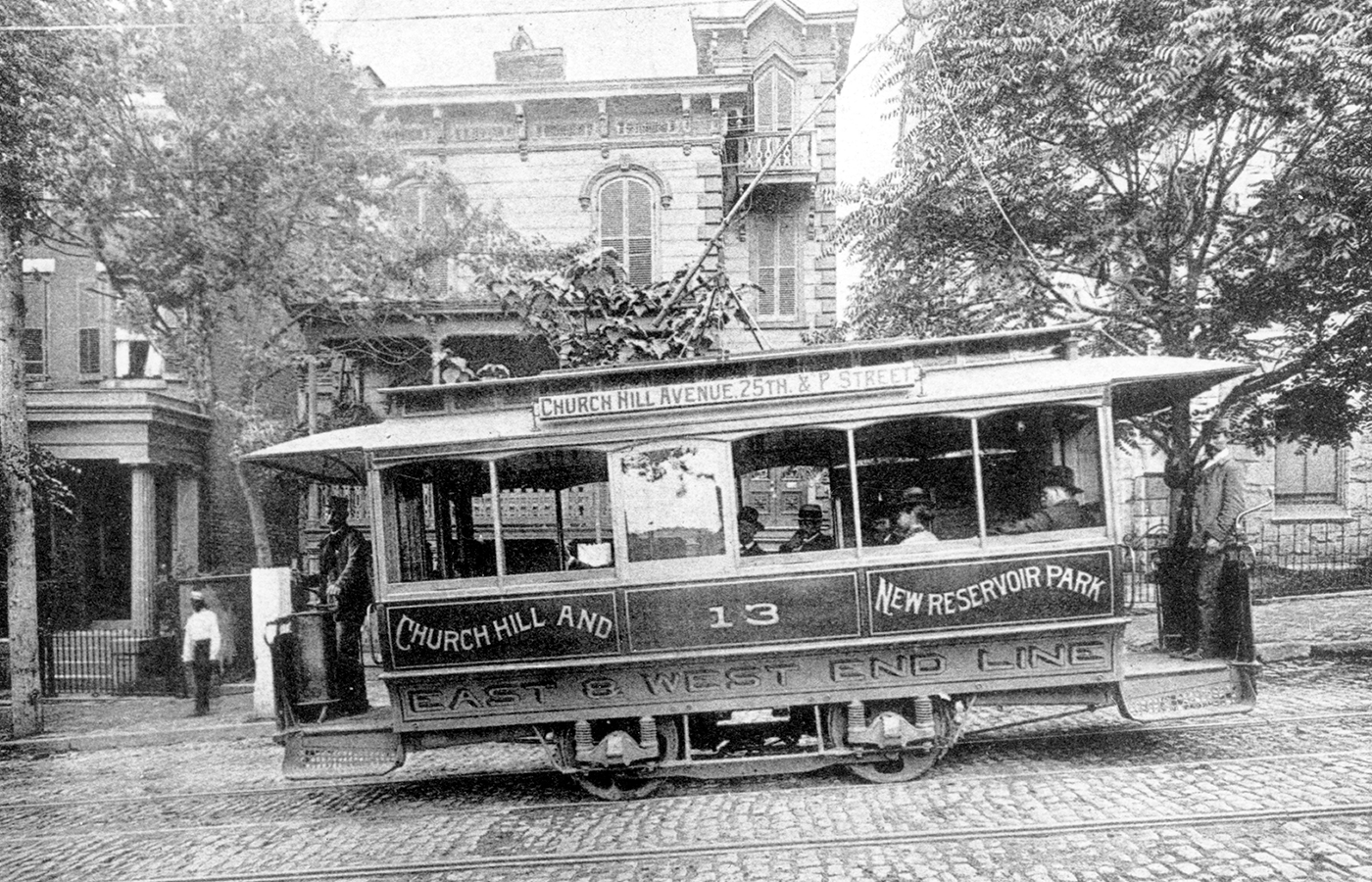

An 1890 photo of an electric streetcar motoring along cobblestone streets in Richmond. (Courtesy of The Valentine)

Sprague bets the house

Work on the “Clay Street line,” connecting Church Hill with the intersection of Clay and Hancock streets in present-day Carver, began downtown, on a steep patch of Franklin Street just east of the state Capitol, and oscillated between setbacks and DIY fixes.

Sprague got typhoid fever. His crew had to rip up the city’s ramshackle horsecar rails before installing new tracks. When testing began, Sprague ran his streetcars uphill at night to avoid public failure. His team burned out motors and had to fetch mules to haul broken-down trolleys back to the car barn.

The last problem forced Sprague to redesign his motor for more power. “They have someone working on the design in Providence [Rhode Island],” Most says. “Old motors were being shipped to Sprague’s New York factory by train and repaired ones were returned. He’s just driving himself into the ground. But it’s the only contract he has. He has to prove it works.”

Sprague spent $75,000 of his own money (about $2.5 million today) to complete the Clay Street line, finishing on May 15, 1888. The next day, he did what any other Gilded Age inventor would do after a bruising but successful trial run: He sent a sales pitch to a rich industrialist.

His letter to Henry Whitney, president of the West End Street Railway in Boston, found a receptive ear. Whitney had been weighing how to modernize Boston’s horse-drawn railcars, which were transporting some 90 million passengers a year on some of America’s most congested streets.

Six weeks later, in the dead of night and with Whitney present, Sprague lined up 22 streetcars at the bottom of Church Hill and instructed his crew, basically, to floor it. One by one, the cars hummed to life, their lamps dimming but never losing power. All 22 made the ascent. Whitney and his associates left Richmond the next day, Most wrote, “their questions answered, and their city’s future decided.”

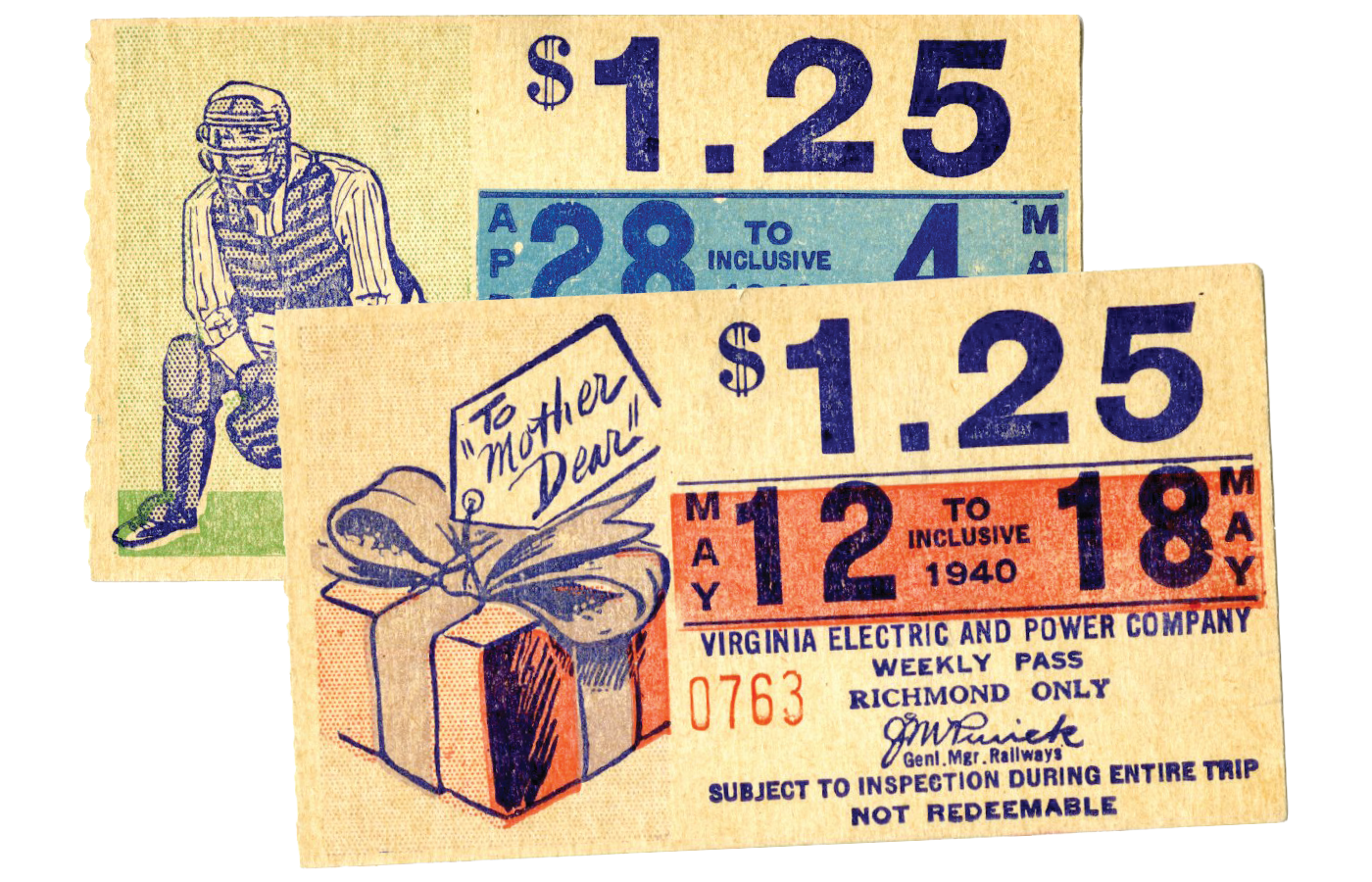

Weekly streetcar passes from VCU Libraries’ Richard Lee Bland collection. (VCU Libraries)

The streetcar era

By 1895, U.S. cities were blanketed in 11,000 miles of electric street railway, according to the International Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Tens of thousands more miles followed.

Built with private capital and managed by private companies, the railways, through government contracts that defined transportation as a public good, enjoyed state-protected monopolies in exchange for maintaining the tracks and pavement and providing cheap, ubiquitous service. Fares were almost universally 5 cents a ride (about $2 today).

Able to now easily ride in 10 minutes what had once taken 30 on foot, Americans could live farther outside town. A real-estate boom followed, birthing a new neighborhood: the streetcar suburb. Some of the first, including Ginter Park and the Fan, were in Richmond.

“You can still see the fabric of the neighborhoods,” says Jim Smither, an assistant professor of urban design in VCU’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs. “People needed to walk to the streetcar, so you will find curb and gutter and sidewalks throughout these neighborhoods, often with street trees. They’re fairly dense. Often they were mixed use, so you were able to get things like food and other necessities of life within the neighborhood — there was the butcher shop, there was the bread shop.”

As railways grew, so did their suburbs: The historic plaques that today adorn houses in the Fan and Museum District date to the streetcar’s turn-of-the-20th-century heyday. Richmond annexed the neighborhoods in 1906, “in direct response to the trolley,” Smither says.

By the early 1920s, the streetcar had reached its zenith, with Americans taking nearly 13 billion annual rides, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. (In 2023, passengers took 7.1 billion rides on all forms of U.S. public transit.) In Richmond, Frank Sprague’s Clay Street line grew to 80-plus miles of track by 1930, with routes extending through Northside, west to the University of Richmond and south to Forest Hill Park.

But it was already the beginning of the end. By midcentury, the American streetcar was all but gone, killed off by the automobile and the very deals that gave the railways their monopolies.

Richmond’s streetcars paraded downtown on Nov. 25, 1949, their last day in service. (Richmond Times-Dispatch)

‘An outmoded nuisance’

The 5-cent fare, agreed to during a long period of low inflation, backfired during World War I when labor, manufacturing and energy costs soared.

And the railways couldn’t change the ride price.

“You had to get the approval of a state body, usually the state public service commission,” says Peter Norton, an associate professor of history at the University of Virginia and the author of “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.” Manned by appointees or elected officials, the commissions scored political points with voters by opposing fare hikes.

Then, in the 1920s, more and more cars began appearing on city streets, making it impossible for streetcars to maintain schedules.

“That model — transport as a public service to be regulated by the state in the public interest — made street railways work,”

Norton says. “They do not work if you redefine getting around the city as a free-for-all. Parked cars lining the curbs, cars driving along the streetcar tracks — in a way, the railways were working in a world of regulation, while the driver was working in a world of increasingly less regulation. And the railways found themselves stuck behind cars.”

Choked in gridlock and wearing a financial straitjacket, streetcar companies slipped into a death spiral of labor and service cuts, worker strikes and plummeting ridership. Some switched to buses. Others were gobbled up by National City Lines, a company backed by General Motors, Standard Oil and Firestone Tire that scrapped railways and converted them to bus routes.

The GM-led backers later were convicted of antitrust violations, but by then, the war was over. Rubber-tired transport, Virginia Cavalcade magazine wrote in 1958, had rendered the streetcar “an outmoded nuisance — a cumbersome, traffic-snarling ark on wheels.”

Richmond’s pioneering railway labored on, but it, too, was doomed. The day after Thanksgiving 1949, “a crowd in a holiday mood,” the Richmond Times-Dispatch wrote, watched the streetcars parade downtown on their last day in service.

Three weeks later, they were drenched in gasoline and set aflame — the last one, No. 408, refused to burn “for 30 solid minutes,” the Times-Dispatch reported, before finally succumbing, at one point heaving herself upright, “groaning at her seams and flinging fire out into space.”

“They had placed her in a less-dignified position, on her side, so that they could give the flames a swifter headway,” the Times-Dispatch wrote. “But old No. 408 died the way she had lived. Right-side up and spitting sparks.”