Arts & Culture

The Inside Out of Valerie LaPointe’s Story

As a kid, the VCUarts alum dreamt of little mermaids and being a Disney animator, but she found joy at Pixar as a storyboard artist, producer and now, director.

It was 60-some degrees outside, but sitting in her Pixar office Valerie LaPointe (B.F.A.’03) wore a little scarf. Even with the neckwear and no blue hair, the resemblance was obvious, especially if you just watched “Inside Out 2” that morning.

Valerie LaPointe is Joy, the film’s starring emotion. Or at least they share pieces of the same essence.

“They were still trying to figure the story out,” LaPointe says from chilly Pixar HQ in Emeryville, California, just a pinch north of Oakland. She’s relaying the origins of the scene in the first “Inside Out” when Joy and her colleague Sadness get launched into the wilder-mind of a despairing tween girl named Riley.

“Something really has to affect Riley for this to happen,” LaPointe says, “and I started sharing this personal story I had.”

This is 2011 and the then-30-year-old LaPointe was working in the novitiate of her feature film storyboarding career. Pixar hired her out of its story internship program that acts as a farm system for the studio’s storyboarders of tomorrow. Interchangeably called story artists, they riff out a movie by hand drawing the scenes and sequences to be filmed/animated later.

LaPointe, now 43, was in the program’s inaugural class in 2006. Today, by virtue of ace storyboardmanship, she is an up-and-coming director at Pixar. LaPointe helmed two episodes of 2024’s “Dream Productions,” a four-episode “Inside Out” spinoff miniseries on Disney Plus, and served as an associate executive producer, a job just a few ranks below director, on “Soul” and “Inside Out 2.”

She was a general-issue story artist on the first “Inside Out,” and that’s how she came to tell this story about herself that became a story about Riley.

“When I was in the sixth or seventh grade, about the age of Riley, I had to start at one of those giant middle schools,” LaPointe says. “It’s like hundreds of kids and everything’s in these classrooms, and I hadn’t moved [to a new school district] but I was in this whole new kind of world because I didn’t have friends in the class and suddenly there were all these new people and the teacher was more stern. I just remember being really overwhelmed.

“I went to ask the teacher a question, and she was kind of brusque with me and a little rude, and I just started crying, and then it turned into this really embarrassing memory I have that really changed my perception of school, from going to the little elementary school to this big environment.”

Valerie LaPointe was in the first class to graduate from Pixar's story internship program in 2006. Today, she's an up-and-coming director. (Photo courtesy of Pixar; illustration by Mitchell Moore (B.S.’07, M.S.’08))

In 1995, Pixar released “Toy Story,” the first feature-length completely computer-animated film. It was remarkable for being that, as well as the extinction event for American big studio hand-drawn animation, an industry Disney defined since “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” opened on the winter solstice of 1937.

“Toy Story” also is remarkable for not having a traditional, classically evil wicked queen-style villain, though if you had to pick one it’s Woody.

“They were trying to make a different type of movie,” says Jim Capobianco, a former Disney and Pixar story artist. “You see that — ‘Toy Story’ comes out the same time as all these musicals at Disney — because they were trying to tell basically a live-action film in animation.”

Capobianco worked at Pixar for nearly 20 years, notably as the lead story artist — officially, head of story or story supervisor — on “Ratatouille” while helping start and run the intern program that educated LaPointe.

After graduating in 1991 from CalArts, a locus for animation talent that nursed brand-name Pixar directors Brad Bird, Andrew Stanton and Pete Docter, Capobianco greenhorned at Disney as a storyboarder on “The Lion King.” In 1997, he expatriated to Pixar, which Disney annexed in 2006 for $7.4 billion. Before that, Disney only distributed Pixar films.

“When I was at Disney, animators were the top dogs. Everything revolved around the animators,” says Capobianco, who directed 2023’s “The Inventor,” a stop-motion film about Leonardo da Vinci that won the Annie Award — the animation industry’s Oscars equivalent — for Best Independent Animated Feature.

“Even though we were story artists,” Capobianco says, “we were just kind of second tier, like an afterthought in some ways. When I got to Pixar, story was held up as the ultimate. We were like the fighter pilots, whereas at Disney we were the ground crew or something. There was even a giant sign up [at Pixar] that said, ‘Story is king.’

“When I was at Disney it was frustrating to me because they weren’t focused on story like that. It was really about musicals, and they found this formula they were following. It’s not like they ignored character and all those things but it just wasn’t top of mind, in a way.”

Joy, left, is the starring emotion of the “Inside Out” franchise. (Courtesy of Disney)

There was once a girl named Valerie who liked to draw the Little Mermaid. She was the third of four kids and from a prolific, extended Catholic family of French-Canadian origin who settled in Westfield, Massachusetts. She grew up in Virginia Beach, though, because the Navy stationed her dad there.

Valerie, her two older sisters Nicky and Michelle, younger brother Charlie, mom Shirley and dad Bruce regularly visited the aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents back in central Massachusetts. Grandma, an exuberant woman, could really hold a room. Grandpa, a quiet wit, had a way with one-liners. They could have had an act but vaudeville went out of business too soon, and it wasn’t ever really that big in Westfield anyway.

Valerie would listen and laugh as her relatives told stories about growing up rambunctious in rural New England, climbing trees, pestering wildlife and during one winter falling through a frozen pond on the way to the sixth grade. Don’t worry. Bruce was OK, and even he admits it’s a good story.

Inspired by family orature and Ariel’s adventures under the sea, Valerie started telling and drawing her own stories. She doodled, sketched and colored for hours a day and often after bedtime. When she was 12 years old, she wrote and mailed a letter to Disney high command asking how she might come to work for the company one day. She also pitched a frog prince movie.

In her Pixar office, Valerie LaPointe is talking with both arms, both hands, most of her fingers and all of her eyebrows. It’s obvious she’s a recovering theater kid.

She has just described her first day at Brandon Middle School in Virginia Beach as she described it in 2011 for the “Inside Out” storyboarders, production sorts and directors.

“I shared that story,” LaPointe says, “and then that snowballs and it’s in other people’s minds, from Ronnie [del Carmen] the co-director talking about it and then [director] Pete [Docter] absorbs it, and the next thing you know that folds into this big moment in film.” In the movie, Riley despairs over changing schools and losing friends. “That’s what’s so interesting about how these films are made. They’re such a cumulative experience. … That’s what’s unique about being a story artist at Pixar. There’s this saying that Joe Ranft had — he used to be the big, head of story when Pixar first started — and he would say, ‘All story, no glory!’”

Here, LaPointe laughs. She’s definitely taken an improv class. It seems like she’s carbonated, in a cosmic way. It makes sense that she was once Joy’s voice.

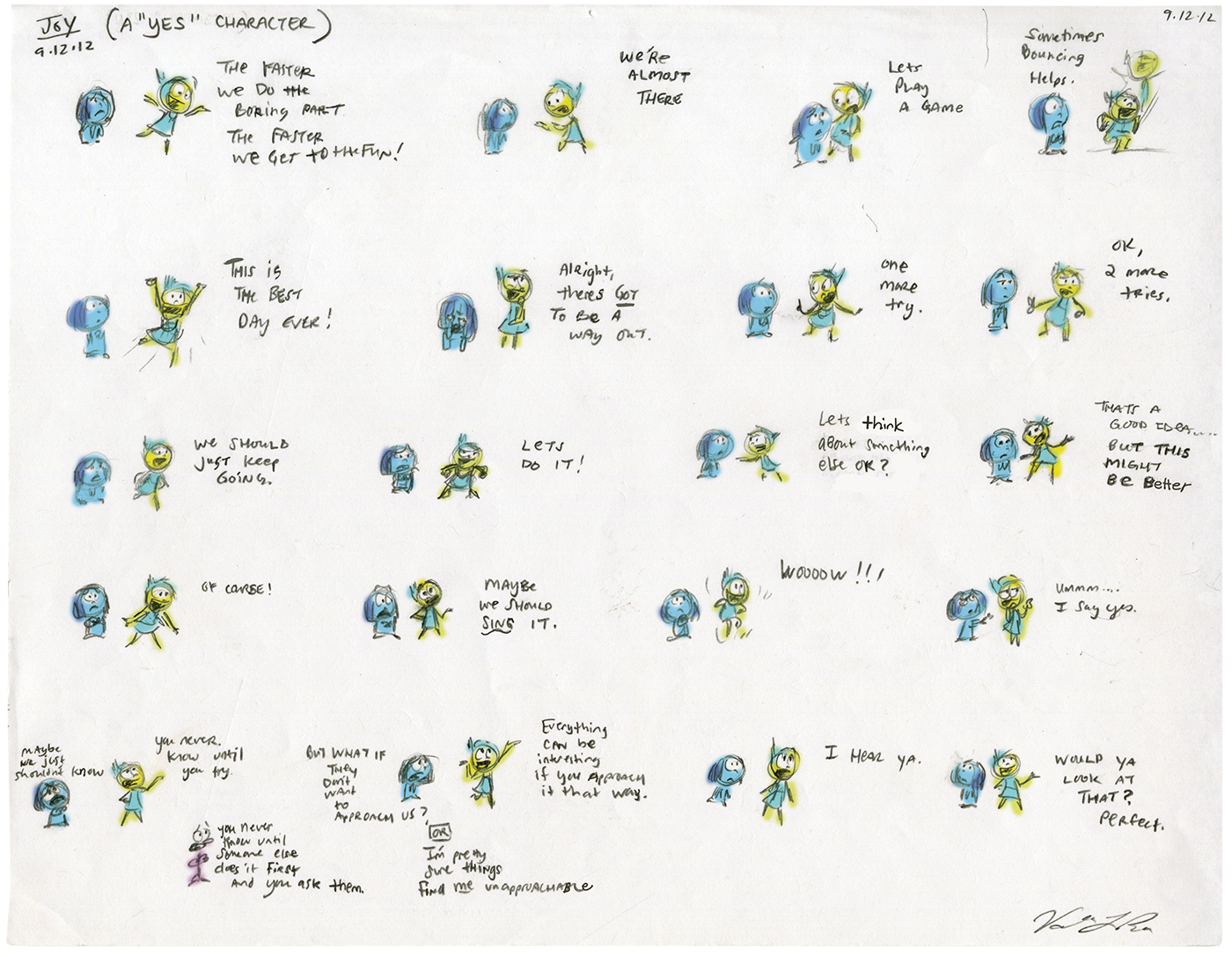

“Joy's personality was not defined, and Pete Docter asked us to brainstorm: ‘Who is Joy?’” LaPointe says. “I felt I knew this character, so I did some mental improv of what a ‘yes, and’ more extremely optimistic version of myself would say — and then the counter personalities of others in my life who are extreme downers. These and a handful of other tiny sketches were what I pitched.” (Courtesy of Pixar)

A few years before “Snow White” made record heaps of money and got Clark Gable misty at the premiere, Walt Disney began hiring fine art professors to train his scampy young artists.

Reid Mitenbuler writes in “Wild Minds: The Artists and Rivalries that Inspired the Golden Age of Animation” that Disney brought in instructors from what would become CalArts to teach classes five nights a week. About 150 artists went to each session, attendance likely boosted by the nude models. (Disney’s animators were all men. It was the industry standard of the age.) By 1935, the classes cost Disney $100,000 a year, about $2.3 million in 2025.

None of Disney’s competitors, not even his great rival Max Fleischer, were doing anything like this. They still had their guys toiling in the animation sweatshops of New York, firing out gag-based shorts at volume to play in theaters between the newsreels and the features.

Disney wanted his studio, founded in 1923, to evolve from the ubiquitous “squash and stretch” style of Fleischer’s Betty Boop and Popeye, Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat and even his own early Mickey Mouse cartoons.

In 1937, his artists produced “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” the first feature-length animated film in U.S. history. It was the highest-grossing American movie at the time and it got Disney an honorary Oscar. The Academy wouldn’t add the Best Animated Feature category until 2001.

“Snow White” still defines the classic Disney style, which got all hot and resurgent in the studio’s golden age of the 1980s and ’90s. The film is immanent in “The Little Mermaid,” “Beauty and the Beast” and “Aladdin.” And like “Snow White,” those movies are fairy stories. Disney was rediscovering its classics.

Disney’s lawyers wrote back to Valerie. They said the studio did not accept outside pitches, no matter how adorable. But it wasn’t all doom and discouragement. Disney offered career advice.

In what was probably a stock letter, the studio recommended to Valerie taking every kind of arts class she could, from life drawing to theater, and attached a short list of expensive but reputable animation schools.

So Valerie went to art college, first for a bachelor’s in animation and kinetic imagery from VCU and then a master’s in animation from the University of Southern California.

At VCU’s School of the Arts, she would skip weekend social time — and once, lamentably, a Strokes show at the 9:30 Club — to hang back in the dorms and make art for school and fun.

For a short experimental animated film, she painted a million (or so) watercolor vignettes and entered the resulting three-minute movie, “Night Light,” in festivals, earning an honorable mention at one hosted by UNC Greensboro. It memorializes friends who died in a car crash.

At USC, she made another short animated film, this time in stop-motion and with a traditional plot. The five-minute, Dr. Seuss-inspired “Lolly’s Box” is about a little girl who travels to another planet with a magic bear.

She put a DVD of “Lolly’s Box” in her application portfolio to be a storyboard intern, not at Disney but at its animation heir: Pixar.

Valerie LaPointe draws storyboards in her Pixar office for the first “Inside Out” film. (Courtesy of Pixar)

Out of Pixar’s exaltation of story came the studio’s famous and widely taught “story spine.” It’s a simple manual for story construction and it’s creeped and seeped into film and writing school curriculums. It’s logical and intuitive at the same time, an armature for ordered inspiration. It goes like this:

Once upon a time, there was [this character]. Every day [the character did this], but one day (oh no!) [this happened] and because of that [this happened] and then [this happened], and finally, because of all that, [this happened.] Fin.

LaPointe says it’s all “story math,” and it is, and its foundations go back to ancient Greece and Aristotle, who was among the first and most eminent to break down the makings of an effective story. He does it in “Poetics,” a collection of notes from the 330s B.C. that specifically parse tragedy.

Aristotle says a plot should be necessary (action follows logically) and probable (the action is plausible within the plot), that characters shouldn’t be too good or too bad (so they’re relatable) and that definitive characters do definitive, character-consistent things.

He says allusion and innuendo are preferable to spelling it all out because those things force audiences to use their minds and, in the most effective tragedy, their hearts. Without the right ratio of feeling and thinking, even with all the form and structure in the Peloponnese, you’ll never give anyone a proper catharsis.

Jim Capobianco, the former Pixar story nabob, learned this stuff in college.

“[Animation’s] always been — it still is — this bastard child of film,” he says. “I would go take these other courses and start learning about [filmmaking] and they would talk about Aristotle’s ‘Poetics’ in class and [about] dramatic structure, and I would go, ‘That’s what I want to do — and apply it to animation. We need these things.’”

Valerie LaPointe was one of 17 story artists on “Inside Out” and among those most responsible for shaping Joy’s character. Later, LaPointe would even record the scratch track for Joy in “Dream Productions.” (Amy Poehler is Joy’s official voice.) The scratch track is a placeholder, part of the great and onerous rough-drafting of a major motion picture.

At Pixar, it means growing a script over three to five years and infusing it with the lives, losses and loves of the film’s staff. It’s a daring way to make a movie (development is not cheap) but Pixar, in what you could argue might be a safeguard, builds its stories around a universal heartfelt moment. It’s Pixar’s yellow sun.

“That’s when the character finally changes,” LaPointe says. “It’s hard to get to that point where you figure out that good ending, and then ideally that [ending] gives you the tentpole and you’re like, ‘OK, we’re working towards this, so if we get lost in the weeds we can always redirect ourselves back there.’

“Everything before that is: To have change, we all go through this experience of argument where we have the way we are and something new comes into our lives to challenge it. And then we’re pushing against it: ‘No, our old way’s best, new way’s best, old way’s best, new way’s best.’

“Usually in the middle you start to tilt toward the new way, and then something even harder comes in and forces you to rethink it, like how Joy in the middle realizes, ‘Oh, maybe Sadness is valuable’ in the first film, and then all of a sudden things get so desperate she’s willing to leave Sadness behind to go help Riley. And that’s her bad choice before she falls into the pit. Then she’s got to have the real epiphany of, ‘Oh no, actually right now Riley needs Sadness, not me.’”

It leads to the part when Riley hugs her parents and gives that heartbreaking sigh. It wasn’t described in the script. A story artist workshopped it into detailed being. Same thing for that one sequence in “Up” — you know which one — and for the scene in “Inside Out 2” when Riley’s emotions group-hug. And the perfect plumber’s-crack joke right after it.

“If you have an emotional, sad moment when you’re bringing the audience into this space,” LaPointe says, “you need to counterbalance that with a feeling of being uplifted. We can only sit in that [sad moment] for so long before you need the release, and I think that’s very similar to when we’re grieving and you have a good friend who tells you a joke or says something dumb to make you laugh. It pulls you up. That relates to our experience as humans in the world, and it’s part of how I think we’ve recognized it as storytelling. I think we do it intuitively.”

Founded in 1986 with Steve Jobs’ money, though the studio’s provenance goes back to LucasFilm in 1979, Pixar intended to respect the classics but tell animated stories that were more sophisticated and existential than princess and prince.

“Toy Story” explores the nature of consciousness, “Inside Out” the nature of emotion and “Soul” the nature of inspiration. The cosmology of “Cars” is much debated.

“That philosophy, that focus was what differentiated Pixar from all the other studios,” says Jim Capobianco, who storyboarded on “Toy Story 2,” “Monsters, Inc.,” “Finding Nemo” and “Finding Dory,” and “Coco,” among others. “It was held to such high esteem that you had to learn about it, and I think there was a focus on that boot camp idea — you need to break down a film and what makes a good film and how is it structured and all that stuff.”

Of course you still have to be able to draw, too — a gag, an action sequence, one of those moments that makes everyone cry. And Pixar certainly has its storyboard Rembrandts, their styles ranging from gestural to gallery-ready. They get a few days to a week to sketch out a scene, once with pencil and paper and now with stylus and glass. Gone, too, are the sketch-covered corkboards that since animation’s oldest days have tessellated story room walls. Like most things, it’s all on flat screens now.

At Pixar, the flat screens run Pitch Docter, a computer program named for “Inside Out” director and company chief creative officer Pete Docter. Crudely analogous to PowerPoint, story artists feed their work into it and use the program to pitch to the director and their cabinet — “pitch” here being short for “tell us a story.” Rembrandt draftsmanship isn’t everything.

“You need to also sell it,” Capobianco says. “Perform the story or the characters to the room to sell your idea and get everybody to get a picture of what this can mean inside the movie. Even though they’re looking at your drawings, there’s an interpretation people can just have from looking at something, but if you’re presenting, you want to add the next layer and be a performer — and Valerie was amazing at that.

“She’s such a performer, with that energy [she has]. And not every story artist is good at [pitching], either. A lot of them can be very insulated and insular, maybe even afraid to pitch. She was fearless.”

Some of Valerie LaPointe’s character designs for “Inside Out 2.” (Courtesy of Pixar)

Samantha Wilson was a production manager on the first “Inside Out.” She’s now a producer at DNEG, a visual effects company in London, but back in 2011 she enforced deadlines, provided unconditional love (when appropriate) and tossed in the occasional creative suggestion for the movie’s bullpen of storyboarders.

During one meeting, the story artists, all men at the time, were trying to figure out what might embarrass an 11-year-old girl.

“They were coming up with, like, paper airplane-making,” Wilson says. “I’m like, ‘No girl would be embarrassed about that.’”

At least their hearts were in the right place.

“Then Val came on as the first female story artist [on the film],” Wilson says of LaPointe. “She was able to fill [the story room] with a life that maybe those guys couldn’t. I’m not saying guys can’t write women, in general, but she just brought another layer to it, and I think a lot of herself was infused into the female characters of ‘Inside Out,’ too.”

Pixar has several films in production simultaneously and a three-movies-in-three-years release schedule, two in one year and one in another. The studio does not use outside scripts.

“It is really hard for a lot of the writers that work in Hollywood to come adapt to the way that Pixar does work,” Wilson says. “One of our writers had told us at some point, he’s like, ‘I write a draft and then I send it off, and then months later I hear back, and then I have time to do notes and then I send it up. But at Pixar, it’s literally like, hey, can you write the first sequence? Can you write the 35th sequence? Can you write this 12th sequence, like all out of order? Can you write it really fast?’ Because we just need … to see if it’s working [with the rest of the film].”

On average, six to eight story artists are assigned to a movie, the number fluctuating up to 12 or so depending on how production’s going, and they’re free to spitball beyond the scripted action and take alternative passes.

Direction can be as precise as a shot-for-shot disquisition or “crazy stuff happens.” The latter approach produced a scene in “Toy Story 3” when Bonnie is playing with Andy’s toys.

“Artists, sometimes they’re just like machines,” says Capobianco, who worked as a storyboarder with LaPointe on “Inside Out” and stumped to hire her at Pixar. “They can crank out a lot of storyboards and they draw really well and they get staging well and put the camera in the right place, but they don’t necessarily have a unique storytelling sensibility, [but] I could see that in [LaPointe’s] work.

“She has conviction in her ideas and she’s not afraid to push boundaries a little bit more. I think some people try to fit [their ideas] into what we’ve seen before, maybe focus a little more on just action, and she seems to come more from a character point of view. It’s surprising to hear this, but I think that gets missed a lot today. She just, in the development, she just goes deeper than others.”

“Toy Story 4” demanded that. Overlords greenlit the film before anyone had a story, and that caused a scramble. Production churned through directors, producers, editors and story supervisors. LaPointe took over in 2017 as the second and final story supervisor, about halfway through production. The film hit its summer 2019 release date and won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature.

“I think it was just really hard to find that story, and the team never gave up,” Wilson says. “And Val was always great at figuring out the story problems, which is, honestly, I think why Pixar movies are good. … They just spend a lot of time banging their heads against the wall trying to figure it out. Everyone’s like, ‘Oh, it’s this secret thing.’ I’m like, ‘It’s iteration.’

“On ‘Toy Story 4,’ in the beginning we were putting the movie up every 12 weeks, so we’d have screenings every 12 weeks where it was storyboarded, cut with scratch sound and everything, and then we’d watch it and then tear it apart again, and then you strategically decide which pieces to fix as you went along when you couldn’t blow up the whole thing, and Val was so good at that part.”

Pixar story artists often grow up to be Pixar directors. Most of the studios’ 28 movies have been directed by homegrown storyboarders. Twelve of Pixar’s 28 films have won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.

Valerie LaPointe sketches of Woody, Bo Peep and Jessie from the “Toy Story” franchise. (Courtesy of Pixar)

Writer Sara Ellis and Valerie LaPointe have been dear true friends since 12th-grade theater camp. Going to the same populous public schools growing up, they should have met sooner, but Ellis was a self-described “pouty Goth-adjacent kid” and LaPointe, Ellis says, was a “really happy theater kid.” Ships passing in a cliquey adolescent night.

“I think the difference between the artist that actually makes s--- and the artists that don’t are the ones that can get past the discomfort of, ‘Oh, well, this might not be good.’ They just say, ‘Who cares? I’m just gonna make it,’” says Ellis, a fantasy and science fiction writer whose novelette “Crypt Currency” ran in the 2022 Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, the same outlet that first published Stephen King’s “The Gunslinger,” albeit in serialized form.

“I think that’s something that really helped Valerie succeed,” Ellis says. “She has a threshold for getting past that discomfort — just like she wasn’t as good as a draftsman as she wanted to be. That didn’t stop her from telling stories and making projects.”

There once was a graduate student named Valerie LaPointe who decided to be a big brave toaster and apply to intern at Pixar.

She didn’t think anything would come of it. Her penciling could have been better, but she had a smiling-wide plucky mien and a five-minute stop-motion film about a little girl and her interplanetary bear.

“I was shocked to find out that they offered me the internship,” she says two decades later from her chilly Pixar office. “And then when I got here, even then — even then — I looked around at myself and the other story interns and I was like, ‘Yeah, that person is much better at drawing than me.’ I could see they had sort of a classic Disney way of drawing, and the way I drew was just different, right? And again, I had enough confidence to be like, ‘It’s fine. I’ll just keep working at it.’”

LaPointe spent three months at Pixar’s Northern California campus learning story Pixar’s way. It was the summer before her last M.F.A. year at Southern Cal. Pixar hired her full time in January 2007, and since then she’s made herself essential personnel.

She’s worked on five Best Animated Picture winners, storyboarding for “Brave,” “Inside Out” and “The Good Dinosaur.” In 2020, she directed “Lamp Life,” a Disney Plus short about what happened to desk lamp Bo Peep and her porcelain sheep between “Toy Story 2” and “4.” She got fan mail about it. The year before, Variety named LaPointe one of its “10 Animators to Watch.”

Draftsmanship, it seems, really isn’t everything.

“The skill that they told me later that they appreciated about my film that I made at USC was that it was a story,” she says. “It had a beginning, middle and end, and it had heart.”

The End