Education & Social Service

Magic numbers

A fresh look at the wonderful world of mathematics

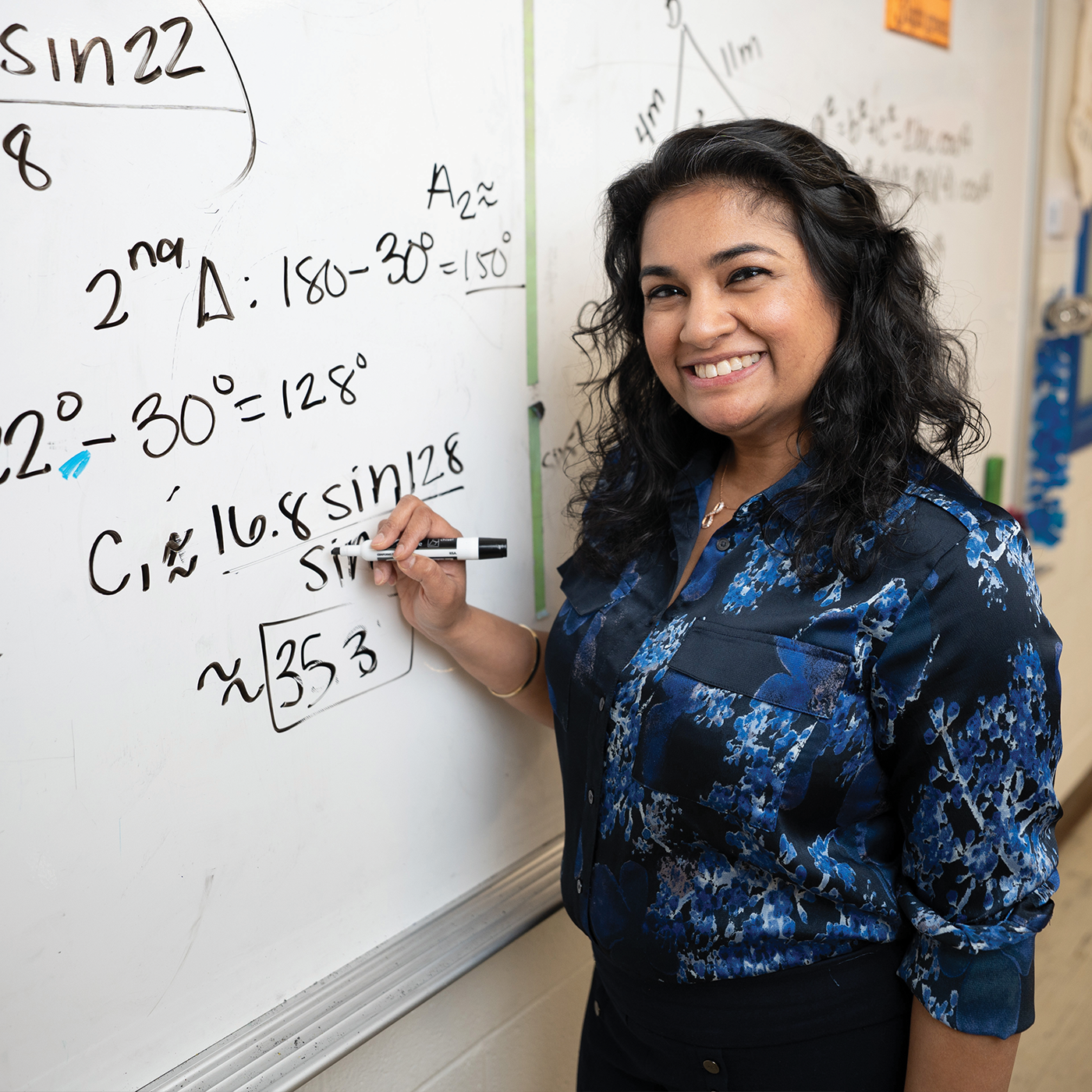

In The Recommendation, a member of the VCU community shares something they love so that you might love it, too. In this installment, 2025 Virginia Teacher of the Year and Hanover County precalculus teacher Avanti Yamamoto (B.S.’12) recommends math.

I became a math teacher because I love math. And it baffles me — it’s heartbreaking — how many people don’t and instead buy into this narrative that they are “not a math person.”

Think about it: Nobody says, “I’m not a biology person.” Nobody says, “I’m not a geography person.” But people say, “I am not a math person.” I had a student once who would write sonnets on his quizzes about how much he hated math.

I probably shouldn’t tell him about iambic pentameter.

The thing is, everyone is a math person. I know this because everyone uses math.

Say you’re baking something that calls for one half-cup of flour and your one-half measuring cup is dirty. You pull out your quarter-cup and put it in twice, right? That’s math. People do this without hesitation. But they also say, without hesitation, “I’m not a math person.” Yes you are. If you can bake a cake, you’re a math person.

Math is everywhere, and there’s a whole world that opens up when you understand math and can apply it. My job is to introduce kids to that world.

One way I do this is by connecting math to their interests. Every year, my students learn about exponential function, which we use to model things that experience rapid change over time, like population growth. I had a student a couple of years ago who, for a class project, decided to make an exponential model of Steph Curry’s impact on the NBA.

Curry is famous for his 3-pointers. He’s the NBA’s all-time leader in 3s, and ever since he entered the league in 2009, the number of attempted 3-pointers, by all players on all teams, has gone up, from 18.1 per game in Curry’s rookie year to 37.6 this season. It’s a great example of exponential function, and shows Curry’s influence on the sport.

The student got an A on that project. And though he didn’t do nearly as well on the test about exponential function, I would argue that he has a very good understanding of the concept. He clearly gets the content. He used math to have a deeper appreciation of the world around him. That’s a math person.

Many of us learned math in a way that emphasized procedure, compliance and “showing your work” over creative thought. People who doubt their ability to be a math person usually equate it — no pun intended! — with mimicking. They think, “I can’t mimic what the teacher did.” They think this because people who are great at mimicking are often perceived to be great at math. All my friends in high school who were “good at math” followed this pattern: The teacher could do something and they could just do it, too.

But math is not about mimicking, or even process or calculations. It’s about thinking. It’s about learning how to use math. I don’t teach math; I teach the world. My job is to give students the opportunity and confidence to grapple with something. Along the way, I give them tools. Which tool is going to work in this situation? Do I need the screwdriver? The wrench? The hammer?

A lot of people think that math is supposed to just make sense. In reality, we need to make sense of the math. You can apply triangulation, for example, to figure out how tall Mount Everest is. But if you don’t understand that application, if you aren’t given the opportunity to make sense of it, you miss the magic of math. And that’s when you believe you’re not a math person.

My parents are Indian immigrants who came to the U.S. in 1975. When I was growing up, the only subject they could help me with was math, because it’s the same in India as it is in America. It’s our one true universal language. And once you realize that, once you see the world through the lens of math, you see a different world.