Research & Discovery

Field station of dreams

For a quarter century, VCU Rice Rivers Center has been students’ portal to the natural world, playing host to research, restoration and life-changing experiential learning — all a half-hour’s drive from Richmond.

On a mercifully mild afternoon in late January, Ed Crawford, Ph.D. (M.S.’95), stands on the edge of the dock at the Rice Rivers Center, VCU’s 360-acre environmental research facility in Charles City County, Virginia.

“This is our front door!” he announces, arms outstretched before a wide, glittering ribbon of the James River, where a trio of bobbing bufflehead ducks takes little notice.

Crawford, a wetland ecologist with a boyish swoop of blond hair, is the assistant director of the Rice Rivers Center. He’s quick to point out that the name is a bit of a misnomer. “We do focus on rivers but also the watershed and the airshed,” he says. “Because what happens in the airshed is going to impact the watershed. And what happens in the watershed is going to impact the water.”

Translation: You’d be hard-pressed to find an inch of the Rice Rivers Center’s hardwood forests, tidal marshes, pine plantations, cypress swamps, airspace, and, yes, riverfront, that Crawford, his colleagues and their students haven’t inventoried, analyzed or measured.

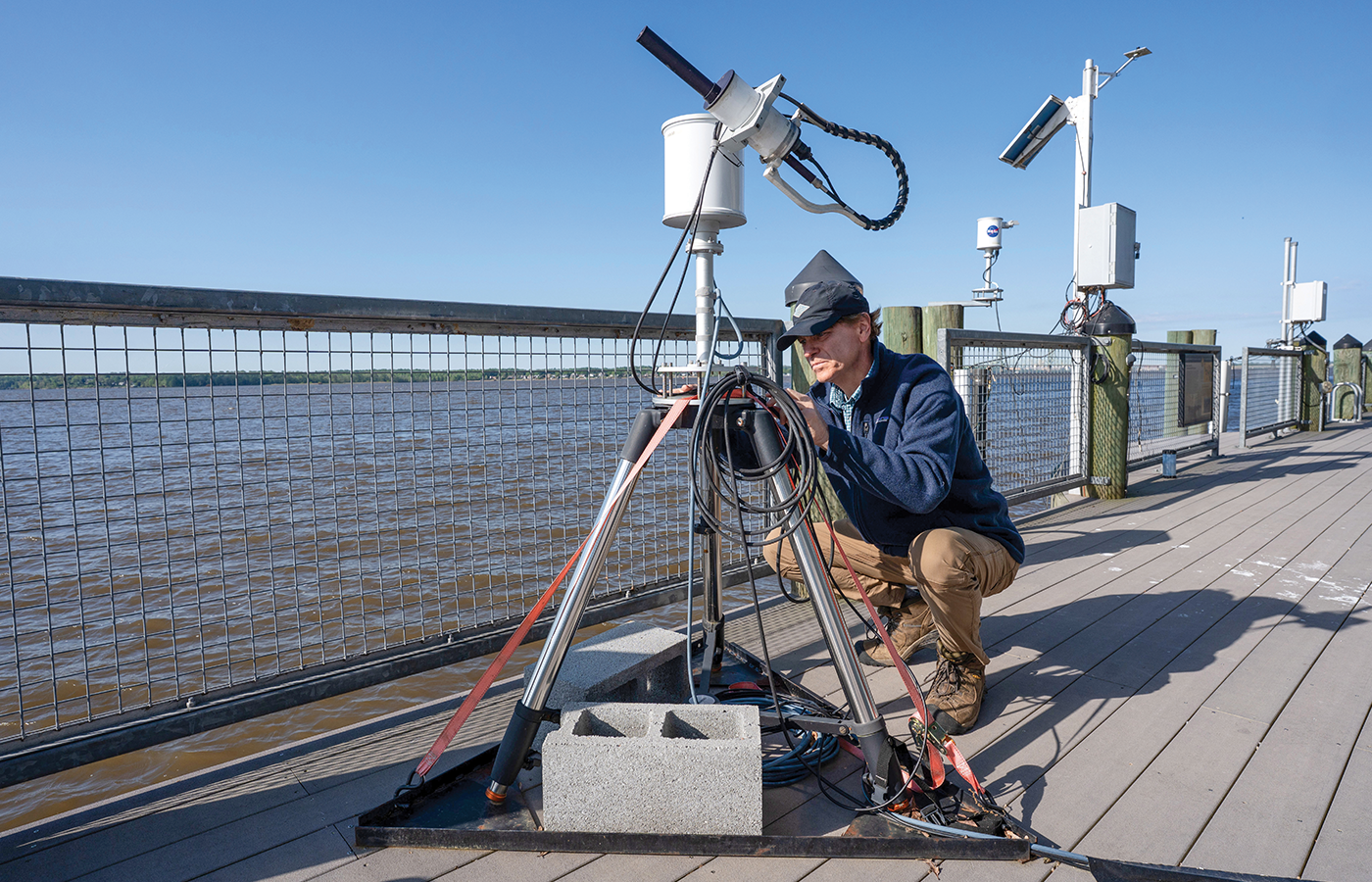

Take this very boat dock. To Crawford’s left, a device called an EXO Sonde is trained on the coffee-colored water, capturing data about its temperature, clarity, pH and dissolved oxygen levels every 15 minutes. To his right, a radar sensor in the shape of an antique telephone receiver is shooting a laser at the surface of the river 10 times a second, recording the water level with submillimeter accuracy. Behind Crawford, two spectrometers and a ceilometer are aimed at the heavens, measuring the ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and formaldehyde in the atmosphere.

All this data is transmitted just up the dock to the 14,000-square-foot Rice Rivers Center Research Facility, where professors, staff and students are working on projects whose focus runs the gamut from tiny warblers to global warming, from restoring wetlands to recovering of iconic species, partnering with agencies like NASA, the Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Geological Survey, to develop and disseminate world-changing science.

This year, the Rice Rivers Center marks a quarter century since philanthropist Inger Rice, courted by housing developers, opted instead to gift her riverfront land to VCU, providing the decidedly urban institution with a no-fooling field station — and its students the opportunity to immerse themselves in meaningful environmental research, just 23 miles from campus.

Life Sciences professor Greg Garman, Ph.D., the center’s executive director from 2016 to 2025, still remembers the Before Times.

“Back in the day, when I taught an ecology class, I’d have to go to Hollywood Cemetery because that was the closest place we could walk where there were trees,” he says, “So to have a place like this — it blew the doors off the possibilities.”

Here’s another thing Garman remembers: the Friday morning in 2000 when he and Leonard Smock, Ph.D., a fellow fisheries biologist who would become the inaugural director of the center, were summoned to VCU President Eugene P. Trani’s office.

“We were both pretty sure we were getting canned,” Garman remembers, sitting in the sunlit conference room of the center’s Walter L. Rice Education Building, the first LEED Platinum building in Virginia, where toilets flush with rainwater and native plants spill from the roof. “We were trying to figure out what we did.”

But instead of a dismissal, the biologists received a directive: Figure out what VCU would do with a field station — and do it fast.

He and Smock worked all weekend, Garman says, to develop a proposal; the following Monday they found themselves standing by Kimages Creek in rural Charles City County, touring a 342-acre parcel of land with the woman who wanted to give it to them.

A native of Denmark, Inger M. Rice had fallen in love with the James River in her adopted hometown of Richmond, where she and her husband, Walter, a former ambassador to Australia, built a home on one of the river’s islands. After Walter died in 1998, commercial developers began calling Rice about the couple’s other riverfront acreage downstream in Charles City County. At first, she was willing to hear them out.

“But when they said they would cut down all the trees, that’s when I said goodbye,” Rice recalls. She knew she wanted the land to be cared for and “to do something for the environment.” Apparently, whatever Garman and Smock wrote in their proposal assured Rice that would happen.

“On the way back to Richmond, she pulled out a yellow legal pad and a pencil and wrote out the terms and conditions of the gift right then and there,” Garman remembers, a hint of disbelief in his eyes 25 years later.

It would be a brand-new chapter for a landscape that has been home to centuries of human culture, conflict and even campfire s’mores.

Until 1618, when the Virginia Company of London showed up and claimed 3,000 acres of Tidewater Virginia, the land had long been used as a seasonal fishing and hunting outpost for the Weyanoke, a tribe in the Powhatan Chiefdom, which once stretched from the present-day capital to the coast. Over the next 2 1/2 centuries, the expanse was carved up for Colonial families, who sowed tobacco and cotton, relying on the labor of enslaved people to create a profitable plantation system. In the summer of 1862, Union Gen. George McClellan and some 100,000 troops set up camp on one of those plantations for six weeks, trampling, clearing and burning much of what is today Rice Rivers Center property. Harper’s Weekly described the scene as “a savage-looking hollow.”

By 1935, the land was teeming with a different kind of camper — YMCA summer campers. Camp Richmond, as it was originally called, was renamed Camp Weyanoke when Native artifacts were found scattered around the property, something Crawford says still happens all the time.

But for scientists like Crawford and Garman, the land’s most thrilling feature is the distinctive ecosystem it occupies — a tidal freshwater habitat. Technically, the center’s front door is not the James River but the James River estuary, the rare body of freshwater that experiences the twice-daily push and pull of the tides.

“In most systems, the tide stops in the salinity zone of the estuary,” explains Paul Zimba, Ph.D., a Rice Rivers Center researcher who focuses on water quality. “But the James is so big the tide actually extends much further.”

Other tidal freshwater systems occur along the Potomac, Delaware and Hudson rivers. Not only are they understudied, they’re also uniquely vulnerable to climate change, Crawford says, mainly because of rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion. An influx of water can drown delicate vegetation and destroy wildlife habitat; an influx of salt can prove deadly to species adapted to freshwater.

Mrs. Inger M. Rice A.M., with Rice Rivers Center faculty, staff and students. The "A.M." stands for the Order of Australia, which Rice received in 2015 in recognition of her work through the Inger Rice Foundation. The foundation helps fund Australian charities and nonprofits whose programs support young children and their families. (Courtesy of Rice Rivers Center)

Figuring out how these systems will fare — and how society will adapt — in a climate-changed future is a major avenue of research for scientists at the Rice Rivers Center, but they’re not taking a passive role in the land’s future. Many are actively spearheading restoration projects to strengthen the resilience of the ecosystem.

In 2010, working with partners American Rivers, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Nature Conservancy, center staff removed a portion of an earthen dam that had been built across the mouth of Kimages Creek, which had long ago turned 70 acres of tidal wetlands and swamp forest into a small, unnatural lake. Reconnected with the James River, today the wetlands are showing signs of rebirth: “tens of thousands of fish, all kinds of shorebirds,” Crawford says, admiring the scene (“my baby” he calls it) from the center’s kayak launch.

At the time of the dam's removal, it was “the largest tidal freshwater forested wetland restoration project in the mid-Atlantic” — Crawford recites it like a mantra.

Staff have also helped neighbors with their own restoration projects, partnering with both the Pamunkey Indian Tribe and Chickahominy Tribe to protect and preserve their ancestral lands. For the former, the center worked with the U.S. Geological Survey to identify critical water resources (as well as threats to them) on the tribe’s low-lying 1,200-acre reservation in King William County.

More recently, Will Shuart (B.S.’98, M.I.S.’01), a VCU Life Sciences assistant professor and geographer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, collaborated to train members of the Chickahominy Tribe to use drones, lidar and remote sensing to map, monitor and manage Mamanahunt, the 944-acre ancestral property the tribe recently reacquired from the state. “We want to show them what they have,” explains Shuart, “so they can create a baseline of data and monitor what is changing on their lands.”

Shuart says none of this could have happened without Inger Rice, now 95, who’s remained “involved and active in everything we do.” Since her initial donation, Rice has funded additional facilities at the center, including the Inger Rice Lodge, which can host up to 22 visitors conducting on-site research or fieldwork.

“Rice Rivers Center could have been a housing development with a golf course; it could have been a Kingsmill. Mrs. Rice had every right to do that,” Shuart says. “Instead she chose to enrich VCU and any student or faculty that visits.”

Cathy Viverette, Ph.D. (M.S.’04, Ph.D.’16), will never forget the first time she visited the Rice Rivers Center. Now its director of student engagement, back in 2001 she was a master’s student, interested in the ecology of the raptors she had become enamored with during a postcollege stint at a research station.

In the past two decades, from her post on the James River, Viverette has witnessed some bird species stage incredible comebacks.

“Today the Chesapeake Bay supports the largest population of osprey in the world,” Viverette says. The reason? “There’s plenty of fish in the sea here.” Rice Rivers Center staff also often see bald eagles ducking into coves and soaring on thermals. Once an endangered species, they, like osprey and others, are now thriving after the 1970s ban on the insecticide DDT.

But the biologist has also seen some bird species struggle. With associate professor of environmental studies Lesley Bulluck, Ph.D., Viverette runs the country’s longest-running study of the prothonotary warbler, a yolk-hued bird that nests in the center’s wetlands. (See “A bird call for wetland health,” VCU Magazine Summer 2024 for more on the pair’s work.) Since the project began in 1987, the bird’s population has declined by about 30%, as the marshy land it prefers continues to be paved over or bulldozed for housing developments.

It’s grim news, but with 38 years and 20,000 banded birds in the books, the project has provided “an incredible dataset,” for students who want to study avian ecology or get field experience working with birds, Bulluck says. “And it’s right here, just a short drive from campus.”

The project has also given students the chance to explore far-off places, with field trips to Panama to collaborate with Central American colleagues and observe the warblers on their wintering grounds.

“This little bird is connecting communities, cultures, countries, continents,” Crawford notes.

It was a big fish, meanwhile, that caught the imagination of Crawford’s former student Matt Balazik, Ph.D. (B.S.’05, M.S.’08, Ph.D.’12), and sent him on a journey even he finds improbable.

In 2004, U.S. Fish and Wildlife staff discovered Atlantic sturgeon, long thought to be extirpated from the James, just outside the center’s “front door.” They’re imposing, spiny creatures, growing up to 14 feet and living up to 60 years, and Crawford convinced Balazik, then an undergraduate biology major intent on studying sharks in Australia, to study “these dinosaurs” instead.

Twenty years later, Balazik, who grew up on the James River just upstream from the center, is a world expert in the prehistoric species, having tagged more than 2,000 sturgeon and establishing the largest fish-tracking setup on the East Coast. Last year he was recruited to help restore sturgeon in England, where the self-described “farm boy” met and talked fish with none other than Sir David Attenborough, the British naturalist beloved by millions for his catalog of nature documentaries.

Balazik says he’s come a long way since his early days of catching — or trying to catch — sturgeon in the James River.

“Back in 2007, we were using gear no one had used in decades, trying to figure out the nuance of the nets, the tides, how the fish moves,” he recalls. “It was comedic how bad we were. It was failure after failure. But we learned. And we got better. And we could do that because we had boats right there on the river.”

Accessible boats were just one advantage. Balazik explains that he and fellow researchers eventually found spawning adults just upstream and juveniles just downstream from the center. “If it was a book or a movie, you would think it was lazy writing.”

Without the center’s support and ideal location, “I wouldn’t be where I am now,” Balazik says, “and neither would sturgeon research.” So far, that research has revealed good news — the sturgeon population is recovering.

Another iconic Virginia species is also on the rise, thanks to work at the Rice Rivers Center.

Launched in 2013, the Virginia Oyster ShellRecycling Program has collected more than 100 million oyster shells from area restaurants and returned them to the Chesapeake Bay watershed in an effort to restore the species, provide new fish habitat and improve water quality. Per day, a single oyster shell can filter up to 50 gallons of water of the excess sediment and nutrients that cloud waterways. “They’re like Brita water filters,” Crawford says.

The “shell pile,” as it’s lovingly referred to at the center, is where millions of those oyster shells come to “cure” — losing all trace of the bacon, cheese and horseradish they were once garnished with — before volunteers and students bag and stack the bivalves, preparing them for their triumphant return to the bay. These so-called bucket brigades are another way for students to develop experience in the outdoors.

“A lot of our students are coming from urban or suburban homes and might not have had the opportunity to be in a place like the Rice Rivers Center,” Bulluck says. “This might be the first opportunity they’ve had to get in the mud, navigate the woods or pull on a pair of waders. It’s such an asset for that reason, a portal to so many good things.”

Despite the backward-facing nature of a milestone anniversary, the future is top of mind for staff and students at the Rice Rivers Center, whether they’re tracking climate change, planning for careers in science or both.

Ph.D. student and faculty research associate Ronaldo Lopez (M.S.’17) is focusing on remote sensing to help solve a nearby climate change conundrum: harmful algae blooms in the Shenandoah River, which have closed the waterway to swimming and fishing several summers in a row.

Working with his adviser, Paul Zimba, Ph.D., Lopez developed a method for using drone imagery to accurately measure how much cyanobacteria (microscopic organisms that can produce toxins) is in the water and developing algorithms that remove interference from confounding elements like chlorophyll.

“The models are 15% to 20% better than what are currently used,” Zimba says.

During his years at the Rice Rivers Center, Lopez has also studied sea-level rise and dabbled in environmental filmmaking, winning the grand prize at the 2018 RVA Environmental Film Festival for his film about oyster restoration, inspired by the efforts of the Virginia Oyster Shell Recycling Program.

“This place has been a platform for me to branch off and try a bunch of different things,” he says.

His fellow doctoral students are working on their own platform, quite literally. In 2016, the Rice Rivers Center became the home of a “flux tower,” a 20-foot-tall aluminum structure that measures greenhouse gas sequestration and emissions with astounding accuracy, providing researchers with a cache of granular data. Part of the Ameriflux system, it is the first installed in a restored freshwater tidal wetland — the same one Ed Crawford affectionately refers to as his baby.

“We want to know: Will this restored wetland function in the same way as a much older wetland?” explains biology professor Chris Gough, Ph.D., who leads the project. Gough says the answer is complicated, but one thing is for sure: “It will take hundreds of years to get back to the old [ecological] system.”

“Rice Rivers Center could have been a housing development with a golf course; it could have been a Kingsmill. Mrs. Rice had every right to do that. Instead she chose to enrich VCU and any student or faculty that visits.”

— Will Shuart (B.S.’98, M.I.S.’01)

Some of the scientists who will monitor that transformation are students in Gough’s lab. “It’s a big deal,” he says, for them to have access to cutting-edge instruments and high-quality data.

“It’s one thing to have the field station and the amazing ecosystems; it’s another to have the world-class infrastructure,” says Gough, also the center’s current executive director. “It makes a quantifiable difference in career trajectories.”

For Eric Bouma (B.S.’22), it was a tree inventory that changed his career path. In the fall of 2022, he was an undergraduate intern for the Army Corps of Engineers, charged with determining how the forest canopy might interact with satellite signals. To find out, Bouma got up close and personal with the Rice Rivers Center arboreal population.

“I inventoried 5,887 trees, collecting their species, circumference and GPS location,” he says. “I did a lot of tree hugging.” All that time in the woods revealed an interest in forestry and land management that Bouma didn’t know he had.

“Rice has been a place that has opened my eyes to so many avenues I never would have thought I’d venture down,” says Bouma, now a graduate student in environmental studies at VCU.

It’s these, center staff will tell you, the life-altering surprises that reveal themselves in the woods, water or lab that make the Rice Rivers Center such a treasure — not just for research faculty or future scientists but for every student who visits, whether they pilot a tricked-out drone, band a warbler’s twiggy leg or simply stand on the dock to admire the James River’s bountiful expanse.

“College should just be magic sometimes,” says Viverette, looking out on the river she’s come to know so well. “You don’t have to become an ornithologist. Maybe you’ll be an engineer or doctor. But there should be moments in college that are so memorable they either change your trajectory or make your life better. That is what this place has given to all of us.”