Health & Medicine

The start of LGBTQ+ medicine

Merle McCann, an alum and HIV/AIDS activist who spent 35 years as a hospital psychiatrist, considers a morbid paradox.

In 1986, Merle McCann, M.D. (M.D.’81), had a first date with a lovely man named John Stuban.

They met at a happy hour in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, hit it off and went dancing. At some point, McCann admitted that he had never seen a sunrise. Stuban just replied, “We’ll have to change that.”

What a smoothy.

They stayed up all night and watched the sun come up over the ocean. There was, of course, a second date. That’s when Stuban told McCann he had HIV.

It didn’t totally surprise McCann, then at the start of his 35-year career as an inpatient psychiatrist in Baltimore. He had met Stuban in the earlier years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has killed an estimated 330,000 gay men since the 1980s.

At the time, the immune system-eating virus had come to be known, pejoratively, as the “gay plague” or more pseudo-scientifically, “gay-related immune deficiency,” and would, by the worst of the crisis in 1995, infect 1 in 9 gay men in the United States.

What did surprise McCann, though, was his therapist’s response when he effused about his new crush.

“I revealed that I was beginning to see someone who was HIV-positive,” McCann says. “And his reaction was, ‘Well, why would you choose to do that when there are other options available?’ It was kind of like denigrating my choice and the fact that this might be a very interesting person to know — and it proved to be quite the case that he was.”

While McCann assumed his therapist would be reasonably enlightened (after all, he was counseling an openly gay patient), the therapist’s reply wouldn’t have been considered nearly as insulting as it would be today, when LGBTQ+ culture has become pop culture.

In a morbid paradox, McCann says, that’s in part because of HIV and AIDS.

“I think everything goes back to HIV,” says McCann, who retired in 2020 after 25 years at Sheppard Pratt hospital, where he specialized in treating patients with mood disorders. “That was what really pushed things, and I think that was important on a lot of different levels — societal, etc. — as far as putting a face on homosexuality in America.”

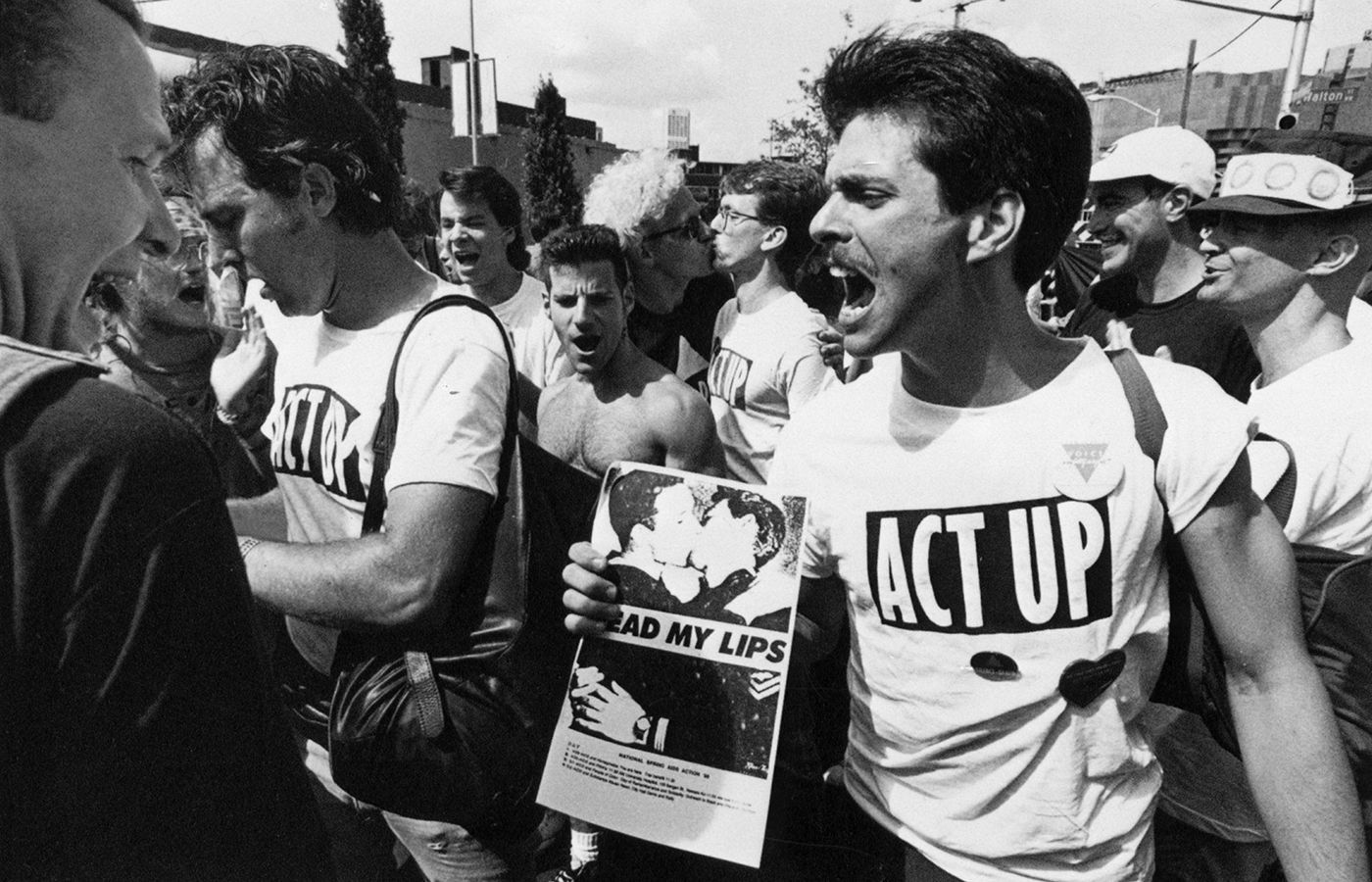

McCann and Stuban were a part of that. Together, they co-founded the Baltimore chapter of ACT UP. Stuban, whom the Baltimore Sun described as “outspoken, uncompromising and unrelenting,” had a reputation for imaginative interpretations of civil disobedience. He picketed the mayor’s home, chained himself to government health buildings and once delivered a coffin to City Hall.

“He was so important in my life,” McCann says of Stuban, who died in 1994 at age 38. The two men were together for eight years. McCann still calls him “my John.” “He kind of propelled me to where I am now.”

John Stuban (right) leads an ACT UP protest. Stuban and Merle McCann co-founded the Baltimore chapter of ACT UP in 1990. (National Library of Medicine)

In the mid-1990s, while abetting Stuban’s creativity (which included a “die-in” outside the Bush family compound in Kennebunkport, Maine), McCann served as the board president of Chase Brexton. Now a five-location chain of nonprofit outpatient clinics in Maryland, it started in 1978 as a men’s sexually transmitted disease clinic, part of the demimonde of ad hoc volunteer-run clinics, shelters and hospices meant to fill in where popular medicine of the era shorted and/or looked askance at gay men’s health.

Hospitals eventually devoted whole wards to HIV patients, but it took more than a decade, and the U.S. government’s response was infamously nonexistent. President Ronald Reagan didn’t mention HIV or AIDS until 1985, and his press secretary Larry Speakes openly mocked the crisis during media Q&As.

“A typical scenario, for example,” McCann says, “was that a gay guy had to go in the hospital with pneumonia, which at that point was basically a death penalty because the illness was so advanced.

“Eventually, the parents would be contacted, and it became like a dual process. The family not only had to deal with the HIV, but oftentimes it was the first time that people from, say, rural areas, the Midwest or wherever, with their sons having moved to bigger cities [for greater social acceptance], learned that their son was gay. The medical staff really wasn’t prepared to deal with that sensitive process.”

Back then, McCann started his days by reading obituaries.

“I was, what, in my 30s, and I was losing more friends than my parents. They were in their 50s or 60s,” McCann says. “I was very accustomed to friends dying. … I called it the AIDS war. That’s what it was really like. It became so much more important to know a person’s sexual history, and I think, up to that point, that was not something that was stressed in medical school.”

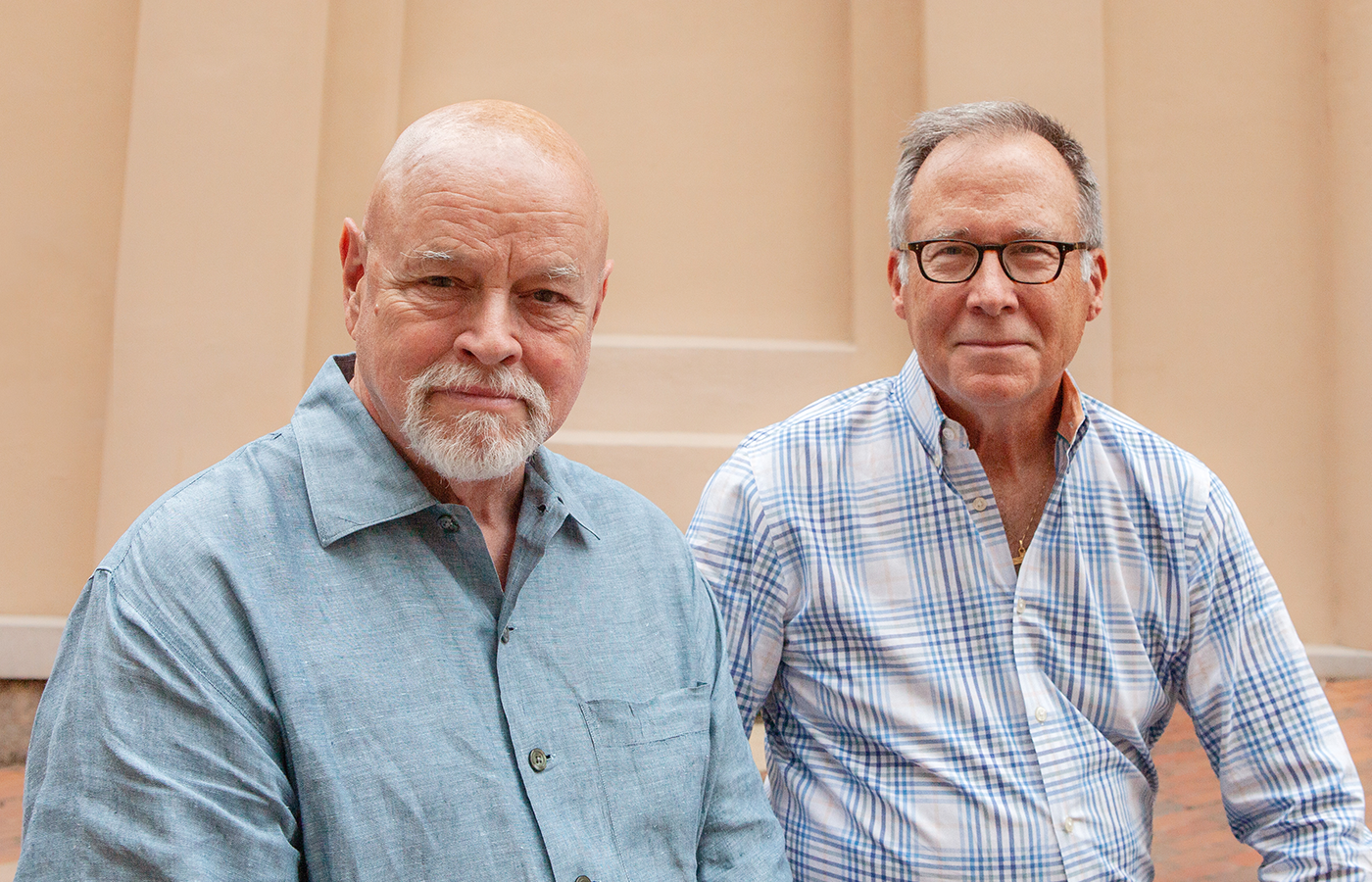

Jared Christopher (left) and Merle McCann. (Penelope Carrington)

Decades later, scholarships focused on LGBTQ+ issues are offered at schools nationwide, including at VCU. This past summer, McCann and his husband, Jared Christopher, established the Merle C. McCann, M.D., and Jared Christopher, RN, Scholarship, a first-of-its-kind scholarship in the School of Medicine for students interested in pursuing careers in LGBTQ+ medicine.

“We’ve moved on to the point where the scholarship — it doesn’t seem weird at all, not now,” says Christopher, who met McCann in 1994. They married in 2009 and now live by the beach in Lewes, Delaware.

Christopher became a registered nurse in 1990 after spending the 1980s volunteering at men’s clinics in rural North Carolina and Virginia, a part of that great filling-in necessitated by the mainstream indifference to HIV and the people it hurt most.

“We had to do that,” Christopher says. “I mean, the government didn’t care. The powers that be — the churches and all that — they didn’t care. They didn’t really care a whole lot until Rock Hudson died.” The gay actor, who was closeted in public life, died of AIDS-related complications in 1985. “Then there was some kind of recognition. You know, as crude as it sounds, we used to say we’re kind of going to need a few hundred thousand white babies to die before anybody’s going to care about us.”

Until 1973, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders classified homosexuality as a pathology. LGBTQ+ mental health professionals, like those who formed the Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists in the late 1960s, fought to correct that. One gay psychiatrist, John Fryer, anticipating retaliation, famously testified about it with a voice-altering device and a mask at a 1972 American Psychiatric Association conference.

“I mean, the government didn’t care. The powers that be — the churches and all that — they didn’t care. They didn’t really care a whole lot until Rock Hudson died.”

— Jared Christopher

McCann says that during his residency in the early 1980s, officials discouraged gay psychiatrists from treating gay patients because of a widely held view in the profession that gay psychiatrists had “too many issues themselves to be effective.”

Coming out could cost someone their career — and not coming out could cost them more.

“How do you reconcile living a gay lifestyle socially and personally but then go to work and not be able to discuss that?” McCann says. “That’s a terrible secret that people felt they had to maintain. And it’s kind of a lie — a lie about themselves and who they are. And people even transpose things.

“I knew people who, say that if they were living with someone, they would talk about their girlfriend or their wife when they actually were with another man, which even takes it further and hits on the idea of internalized homophobia.”

Again, that morbid paradox.

HIV and AIDS forced gay life out of its underworld and into the public — and political power came with it. In 1995, nearly 40,000 gay men in America died of HIV- and AIDS-related illnesses. Only nine years later, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage.

The advances in LGTBQ+-specific medical treatment since the 1980s have little to do with eureka-moment research or laboratory bravura. They came from humanizing a group of people once demeaned as aberrant. In treatment, this meant rejecting heterosexuality as a default as well as considering someone’s unique sexual history or just asking the name someone wants to be called.

“Look at America and how it changed its opinion on same-sex marriage within a generation,” McCann says. “I think that was putting the face on gays and lesbians. You have a next-door neighbor, you have a son, you have an uncle or an aunt who’s gay — that effected major changes and allayed some of the fears of ‘the other.’ I think the political act of daily living your life without lying was a part of the transition.”