Archives

Beyond the scope

A short history of a ubiquitous medical device

The stethoscope has become the unofficial symbol of medicine. A simplified plastic version shows up in every preschooler’s doctor kit, and a metal stethoscope draped around the neck signifies the wearer has survived many years of schooling.

Before the stethoscope, physicians would place their ear against a patient’s chest to listen to the heart and lungs. In 1816, while visiting a young woman, French physician René Laënnec felt uncomfortable getting that close to his patient. Some historians say his wife would have gotten angry; others say it was difficult for him to hear her heart because of her larger size.

Laënnec considered his options. Inspired by children he had seen sending signals to each other using a long, hollow piece of wood, Laënnec tightly rolled up a quire of paper (about 25 sheets) and put one end to the patient’s chest, his ear to the other. He could hear her heart beat!

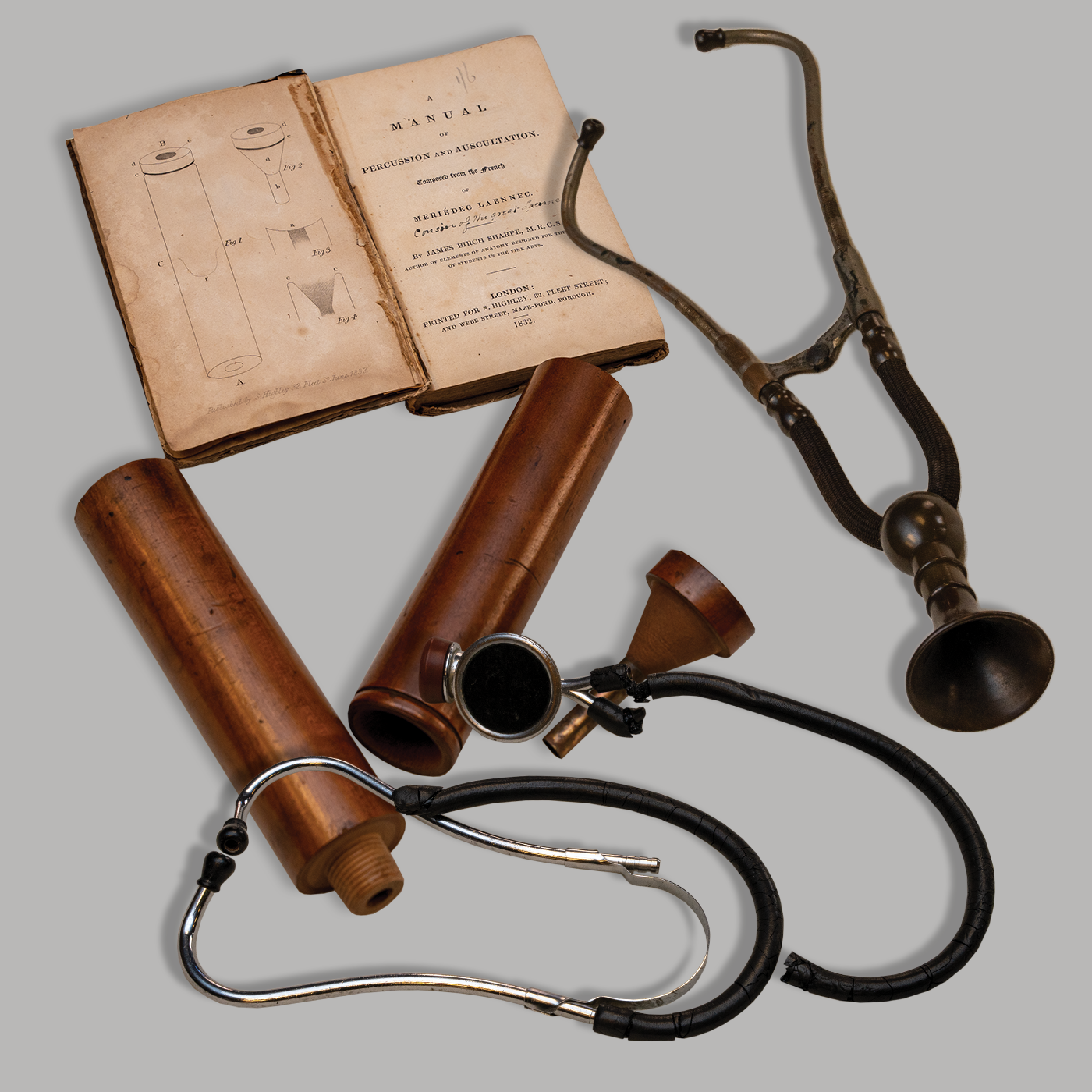

Today’s stethoscope bears little resemblance to Laënnec’s rudimentary device, but the concept endures. Several stethoscopes in the Health Sciences Library’s collection — chosen with help from Margaret Turman Kidd, VCU Libraries’ senior curator for the health sciences — reveal the instrument’s trajectory from paper tube to the Y-shaped device we recognize today.

“Le cylindre”

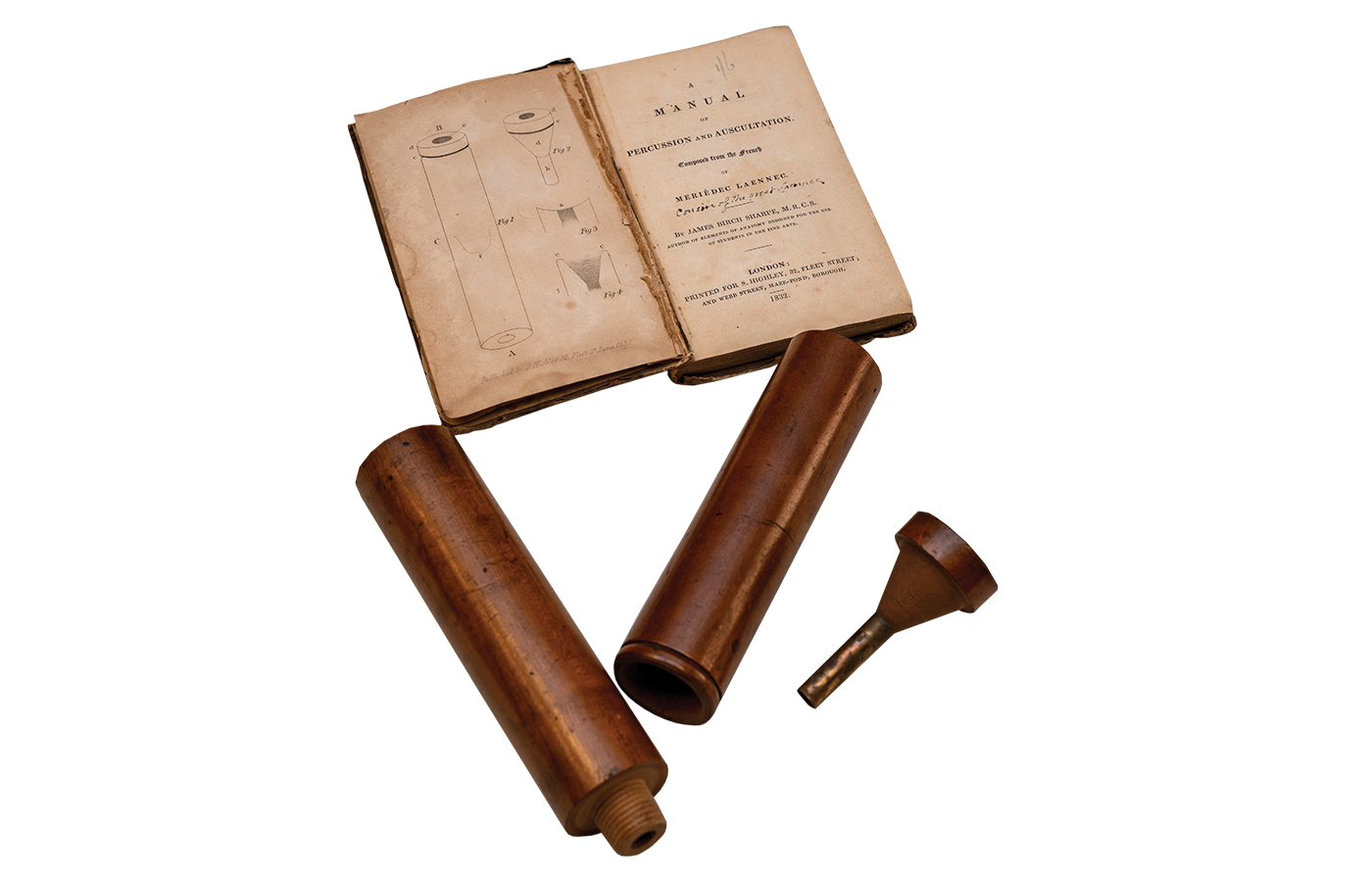

For several years after visiting the patient, Laënnec experimented with more sophisticated designs. He settled on a wooden tube he called “le cylindre.” The tube could be separated into three pieces for easy storage and portability.

In 1819, Laënnec published a treatise that encouraged doctors to use the stethoscope. As with most inventions, there were early adopters and detractors. Seven years later, Laënnec died of tuberculosis, a disease he had tried to better understand through his invention.

An American in Paris

George P. Cammann, an American physician who studied in Paris, was not the first to develop a binaural stethoscope that allowed a doctor to listen with both ears; that was Irish physician Alfred Learard in 1851. Cammann was, however, the first to design a commercially available binaural stethoscope the next year. Ear tips made of guttapercha (Malaysian rubber, which had recently become available) rest on steel tubes that connect at a hinge. Cloth-covered tubes lead to the listening bell. Binaural stethoscopes like Cammann’s enhanced sound, but monaural models remained in use for several more decades.

A long listen

Jean Harris, M.D. (M.D.’55, H.S.’57), the first Black student admitted to the School of Medicine at the Medical College of Virginia, used this stethoscope for 20 years. Unlike earlier binaural stethoscopes, this one has two chest piece options: a bell, which transmits lower frequency sounds from the heart, and a diaphragm, which transmits higher frequency sounds from the lungs. Harris’ stethoscope hasn’t held up well, in part because she used it for so long but also because modern materials are less durable than those used for earlier models, Kidd speculates.