Arts & Culture

Turn back the dial

An ode to old-time radio

In The Recommendation, a member of the VCU community shares something they love so that you might love it, too. Here, Christopher Irving (B.F.A.’99), an assistant professor in the Department of Communications Arts, a doctoral student in the Media, Art and Text program and author of “Cliffhanger! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials (1941-1952),” recommends old-time radio.

When I began teaching in communication arts, I made darn sure to include old-time radio — original story programs from the 1930s through 1950s — alongside film, comic books, video games and television. I think of OTR as the “lost art,” and one that gets overshadowed by television and film, but is actually in the DNA of both.

Radio helped develop the genres and storytelling we experience today through TV and, yes, even newer podcasts. It’s also where the comic book superhero developed beyond the shorter-form stories of their native medium and into serialized storytelling.

Two years after he debuted in the pages of “Action Comics” No. 1, Superman hit the airwaves in serialized chapters in 1940. The waning days of World War II saw Kellogg’s sponsorship push the Man of Steel in a new direction, one that tried to make up for the racism of earlier episodes before and during the war. As a result, Superman became more than just a champion of the oppressed but a fighter of intolerance, fighting for “truth, jus- tice and the American way” — a rallying cry to fight bigotry, xenophobia and racism in all forms. Superman took on, famously, a stand-in for the Ku Klux Klan in “The Clan of the Fiery Cross” and argued for civil rights and fair treatment of all, no matter the color of their skin or the church they went to.

In short, Superman was aware, preaching and practicing progressive ideals on the airwaves up to five days a week.

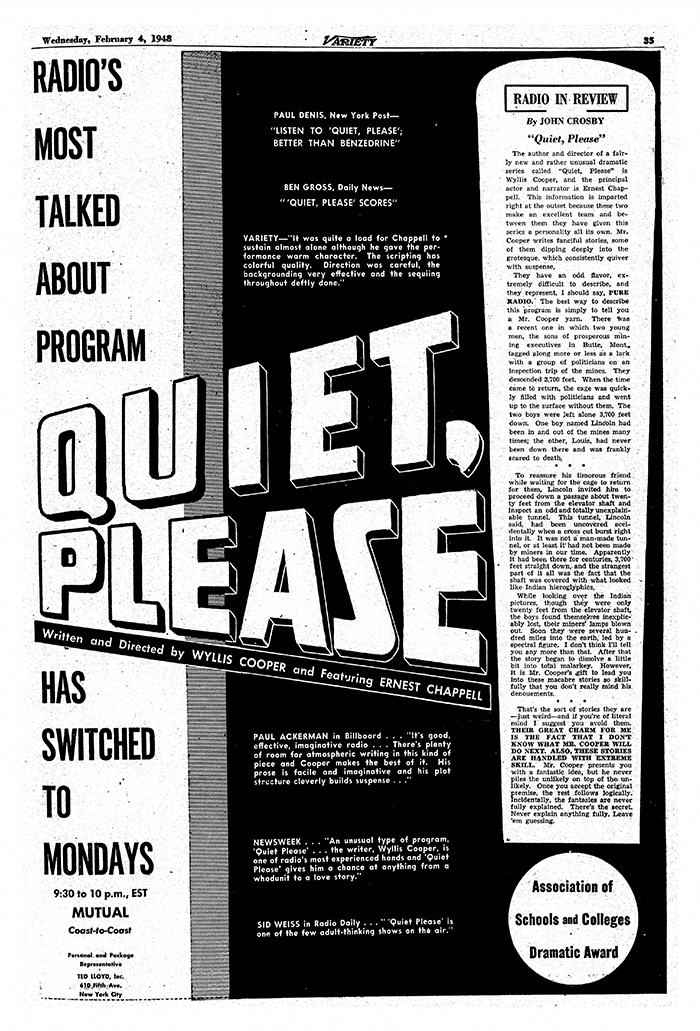

This ad for the radio anthology suspense series, “Quiet, Please,” ran in Variety magazine Feb. 4, 1948.

Radio also thrived in presenting crime and horror stories, from the outright campy, like “Inner Sanctum,” to the utterly terrifying, with “Lights Out” and “Quiet, Please.”

“Lights Out” was a horror anthology show created by writ- er Wyllis Cooper in 1934 and taken over by Arch Obeler from 1936 to 1947 (with a hiatus from 1938 to 1942). Every episode opened with a warning urging the listener “calmly, but sincere- ly” to turn off the radio before the episode started if they wished to “avoid the excitement and tension.” It was a great gag.

A staple in my Horror in Media class is an episode of Cooper’s anthology show “Quiet, Please,” which is an exercise in minimalism that ran from 1947 to 1949, narrated by and starring actor Ernest Chappell.

The episode “The Thing on the Fourble Board” is visceral, from the strains of the quiet piano theme through Chappell’s chilling narration. It tells the story of a man who works an oil rig and, one night, discovers something ... not quite right scrambling on the fourble board, a platform high above an oil derrick. It isn’t what this thing from the subterranean depths is that’s so shocking, but it’s how Chappell’s character deals with it.

There’s so much more I could suggest: “Nightbeat,” where Frank Lovejoy played Chicago Star reporter Randy Stone is my favorite, a cross between Damon Runyon and Raymond Chandler; Jack Benny’s comedy show was iconic and trendsetting; “Escape!” and “Suspense” feature a who’s who of talent behind the mic.

And the best part? Almost all of this is free and accessible online, through archive.org, YouTube or a simple Google search. Many also are available on Spotify and Apple Music.

My advice is to pick a quiet night when it’s just you, dim the lights (or cut them out completely), sit back in your favorite chair and listen with not only your ears, but also your mind.