Arts & Culture

Master of Light

Artist and alum Willie Anne Wright found the dreamy world of pinhole photography by chance — or did she?

Decades ago, artist Willie Anne Wright (M.F.A.’64) was standing by her mailbox when, she suspects, one of her muses spoke from the mystic ether around Richmond’s West End.

“I got a message when I lived on Baldwin Road,” Wright says, with that old Richmond accent you don’t hear much anymore. “I heard a voice say, just as clear as anything, ‘Cultivate your garden.’ And I thought: What does that mean?”

Sixty-some years later in the Fan, Wright, 100 and delightfully prone to wiseassery, is sitting on the couch in her Strawberry Street house, where she and her late husband (and occasional model), Jack, moved in 1972. She’s laughing as she explains the obviously cosmological reasons that, after decades as a painter and a printmaker, she took up pinhole photography, a medium as niche then as it is now.

“It seemed like somebody was guiding me,” Wright says, pausing for effect and then making a spooky “Ahhhhh” sound that in more traditional usages might accompany crystal ball revelations or the ghost of your least favorite grandma. “I was fairly successful with my paintings, and they were being accepted in shows outside of Virginia and all that kind of stuff, so I didn’t need to start something new. But it came into my life.”

Wright now probably is better known as a photographer than a painter, though she continued painting throughout her career. Her work is in permanent collections at museums throughout the East Coast as well as the southeastern and southwestern U.S.

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 1944, eight years after it opened, first showed Wright’s art when it included two of her watercolors in an exhibition of Virginia college artists. Still an undergraduate at the time, Wright majored in psychology at William & Mary (because it was new, she says, and she hadn’t studied it in high school) and only audited art classes.

The VMFA has regularly exhibited Wright’s work since, including a 1970 show that featured her alongside Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko, and has about 250 pieces of hers in its collection. From October to June, the VMFA hosted “Artist & Alchemist,” the first full retrospective on the Richmond artist.

“She’s sort of been part of the museum’s DNA,” says Sarah Kennel, Ph.D., who curated the “Artist & Alchemist” show, the planning for which started in December 2022. “Part of that title, ‘Artist & Alchemist,’ I didn’t really feel like ‘photographer’ described how she sees herself and encompasses her work. I mean, she makes a lot of great photographs, but the idea of ‘alchemist’ — she loved to play with things.

“Particularly the last 20 years of her photography, she moved back into this creating mode — more with her hands. She’s still making images with a camera, or photograms, but she’s using cutouts, she’s scanning things, she’s flipping them. It’s very much bringing painting, collage, printmaking all into what ends up being a photographic image, or she’s just trying stuff and seeing what happens. And you have to be really willing to let go of the outcome when you use pinhole anyway, because you don’t know — because there’s so much you can’t control.”

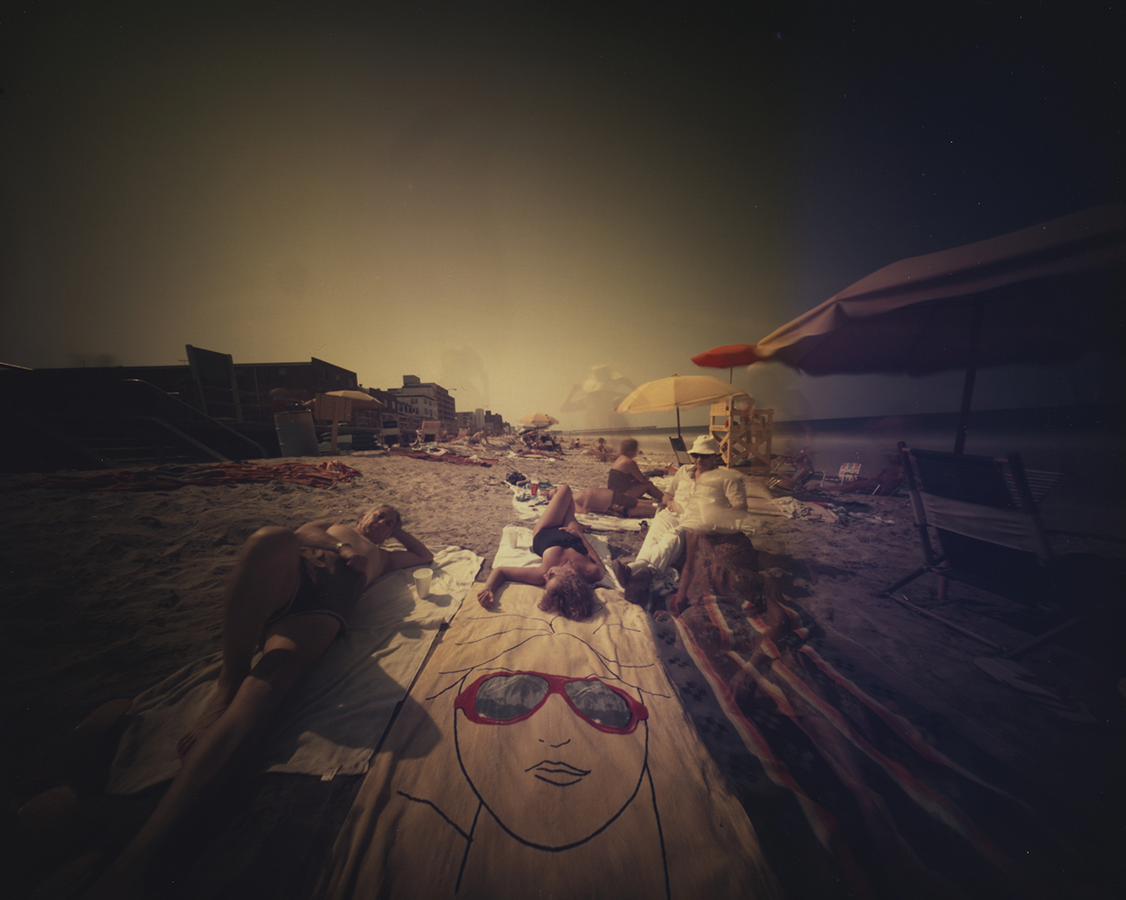

“Virginia Beach — Bernie, Marsha, Jack — Sunglasses, Towel, Labor Day” (1980)

The tale of Wright’s pinhole photography conversion is almost lore at this point.

In 1972, Wright, a compulsive matriculator, took a photography class at VCU so she could learn to take better pictures of her paintings. The professor, the late Department of Photography and Film chair George Nan, started the group on the fundamentals and had them build pinhole cameras, the principles of which were first observed about 2,500 years ago, well before the camera’s Victorian heyday.

“I had some kind of empathy with it,” Wright says. “It was like I was supposed to do it, and it was bringing out stuff in me that I hadn’t had the chance to get to before. It opened up a world and it opened up the history of photography. I never even thought about photography except that Jack would take pictures of my paintings. That was about as far as I got before this.”

A pinhole camera is simple. It’s just a box, sealed completely from light except for the titular pinhole. No lens required. Inside the box, opposite the pinhole, is photosensitive paper. Basic camera film would work. It’s all very DIY-able.

The pinhole aims a thin-but-concentrated ray of sunlight onto the paper and makes an image that, regardless of what’s photographed, will have the feel of a dreamt memory. The light’s intensity and the type of photosensitive paper dictate the exposure time. Figuring that out, though, is more feel and experience than science and technology.

“You control the exposure by guessing. You look at the sun,” Kennel says. “But, really, I think for her, it’s not a perfectionism. It’s really more about the process and seeing what happens.”

“I had some kind of empathy with it. It was like I was supposed to do it, and it was bringing out stuff in me that I hadn’t had the chance to get to before.”

Among Wright’s pinhole innovations is experimenting with photosensitive papers intended for direct sunlight exposure, notably Cibachrome. Developed in the 1960s, it’s known for its full, buttery colors. Killed off in part by digital photography, it hasn’t been manufactured since 2011.

Used in a pinhole camera in intense sunlight, Cibachrome requires a two- to three-minute exposure. It also needs color filters, made of glass or plastic and placed over the pinhole, to match the shifting colors of sunlight (Mr. ROY G BIV at work) to the fixed color sensitivity of the paper. Cibachrome veers blue.

“It is designed to be used in conjunction with slide photography, or transparencies, which is a positive — like the world is a positive [as opposed to a photo negative],” says Gordon Stettinius, founder of Richmond’s Candela Books + Gallery and Wright’s longtime friend and art dealer. “And she was like, ‘Well, reality’s positive. Maybe if I just put this directly into a camera and make an exposure, something good will happen or it’ll make sense.’ And it did. … She understood pinhole photography very well, but the [Cibachrome] was designed for darkroom exposure, so it wasn’t calibrated for daylight, so she wound up having to figure out how to filter that light. And she just pushed and pushed until she became very expert in this very niche practice.

“I saw a show in Santa Fe, [New Mexico] probably 10 years ago of a spectrum of pinhole photography — like a huge survey — and I did see one or two examples of people who sort of glanced up against this, but nobody who did this for 12 or 14 years, just learning it inside and out. I mean, I think that’s how she got somewhere eventually. She just doggedly pursued this.”

Wright saw the pinhole-Cibachrome pairing as a larger bed in her muse’s garden and mainlined her influences into it: psychology, pop culture, feminism, art history and Victorian photography, specifically the haunting works of Julia Margaret Cameron and Roger Fenton. Another influence is the turn-of-the-20th-century mystic Pamela Colman Smith, known today for illustrating the cards for the still widely used Rider-Waite 1909 tarot deck.

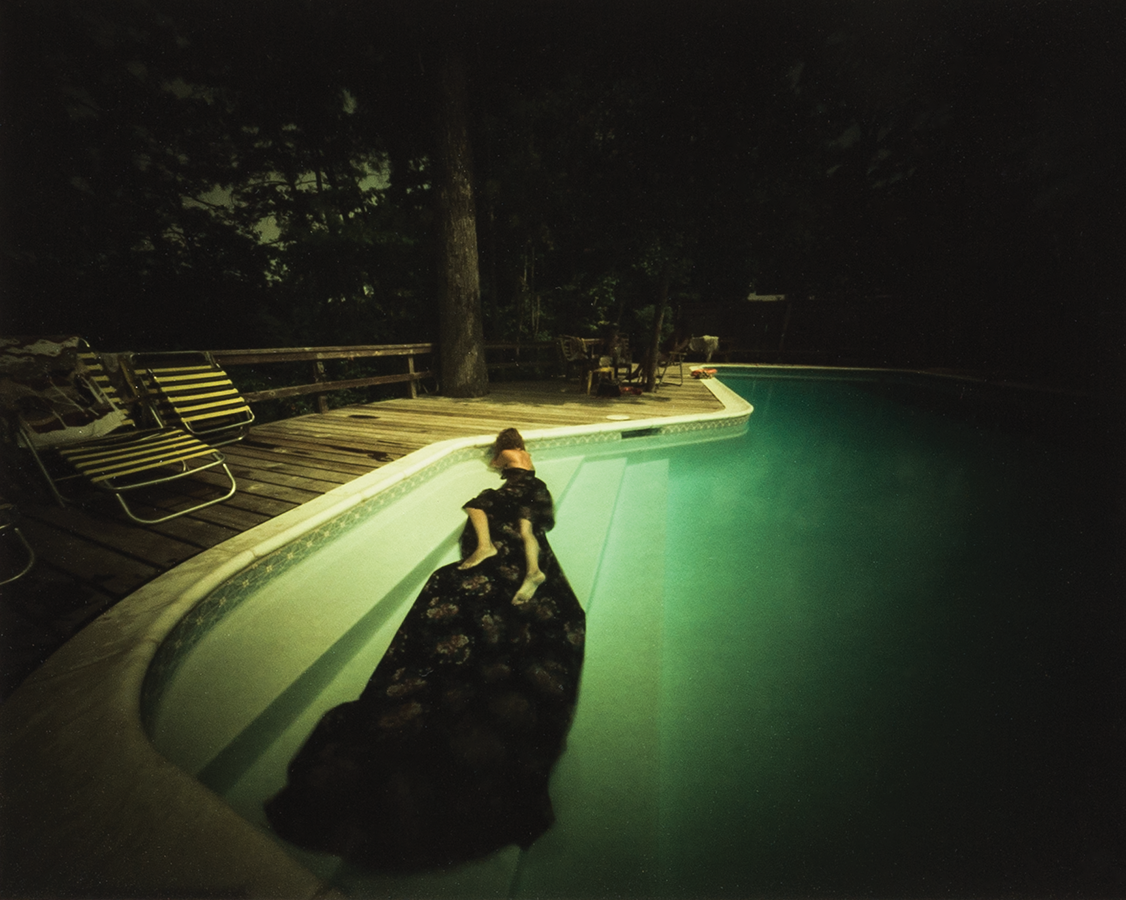

“It’s a long exposure,” Wright says, “and it had to have intense sunlight” — that’s to get sufficient light through the pinhole — “so that meant, OK, what could I take pictures of that would meet that requirement? Well, swimming pools! OK, summertime! You can have girls in bathing suits. You can have people sitting around the pool, having a drink. It just opened up a whole world I hadn’t even thought about photographing, because I liked the way the photographs looked. Many trips to Virginia Beach. You got your subjects lying out on the beach and your setup and then strangers come up and want to know what the hell you’re doing.” They often walked through the shot. “Sometimes it didn’t matter or sometimes it’d make an interesting blob.”

Wright also set up classic still lifes in rural vistas, sequestered gardens and even Maymont Park. One striking-as-it-is-eerie pinhole photograph from 1981, “Still Life With Richard’s Road,” shows a table in a forest-rimmed field in front of a gravel path west of Richmond. The table’s set with a white cloth, a bread loaf and a fruit spread that looks like someone sacrificed Carmen Miranda’s hat to Bacchus.

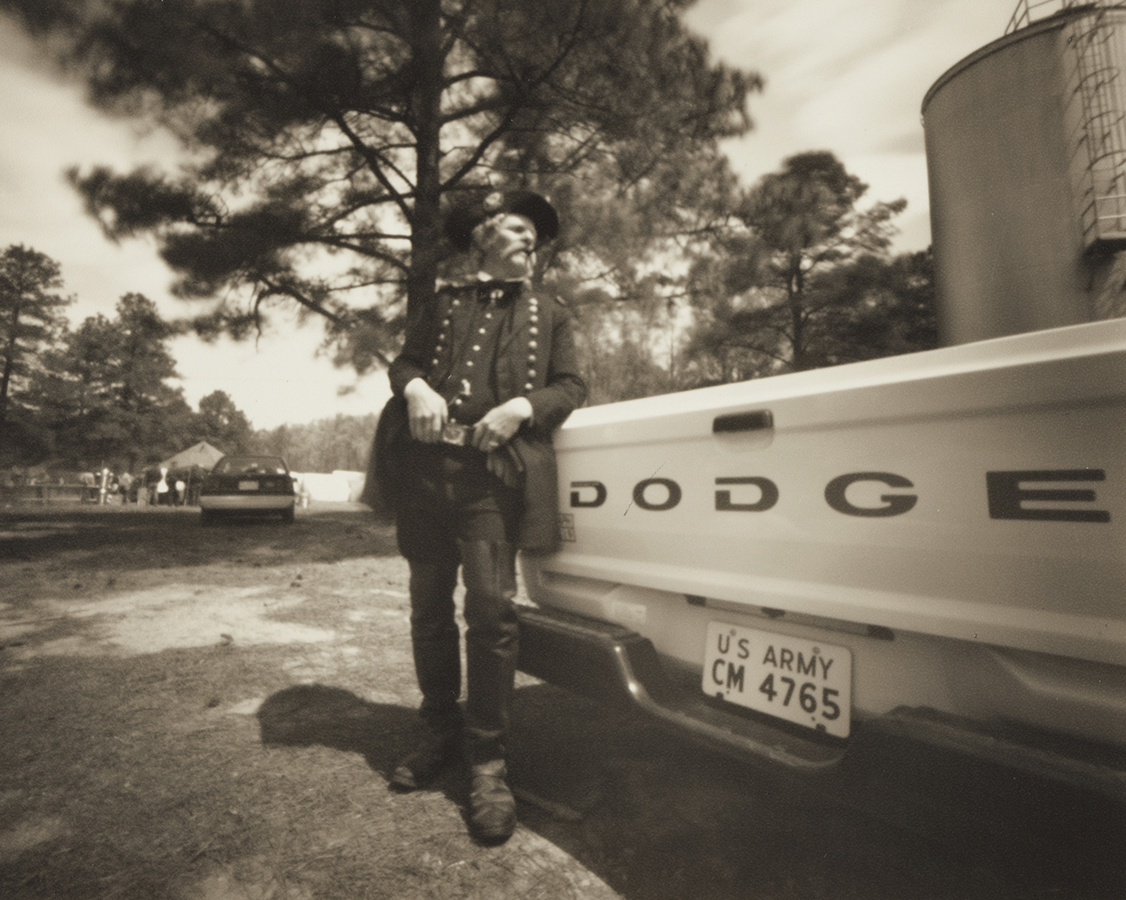

Other favorite subjects for Wright include amusement parks, old houses, cemeteries, pregnant women, general mundanity and Civil War reenactments.

“Another thing that really distinguishes her, I think it’s just a real irreverent sense of humor,” Kennel says. “She’s delighted by the weirdness of contemporary life as well as history, and it’s finding those points where they converge or diverge. In her ‘Civil War Redux’ pictures, for example, she’s not just trying to get at this practice of reconstructing a Civil War battlefield. She’s trying to get into the psychology of the people who do it — the strangeness and their own intense investment with recreating the past. So she homes in on the Civil War doctor and the [wax] amputated leg, and that macabre aspect of it, of course, for her, is very funny.”

Often photography trips demanded hotel rooms, but not because these were multiday trips (even though they often were). Wright needed windowless bathrooms so she could change the film in her pinhole cameras, another wrinkle in a rumpled process.

“It was always like it was almost going to go south, and I wouldn’t get anything,” Wright says. “And then, all of a sudden, I’d go home and process the thing, and, yeah, I had this really nice piece — where did that come from?”

Wright says that pinhole duds were rare and that she could see something in any picture she took. Tucked against the high arm of the Strawberry Street couch, Wright laughs.

“That led me to trying things without cameras — just directly placing the photosensitive material in the sunlight and making lumen prints,” Wright says. “I must say. I think lovingly of photography.”