Health & Medicine

A miracle cure for sickle cell disease?

Gene therapy can change lives. It’s also costly and onerous. Three experts discuss its future.

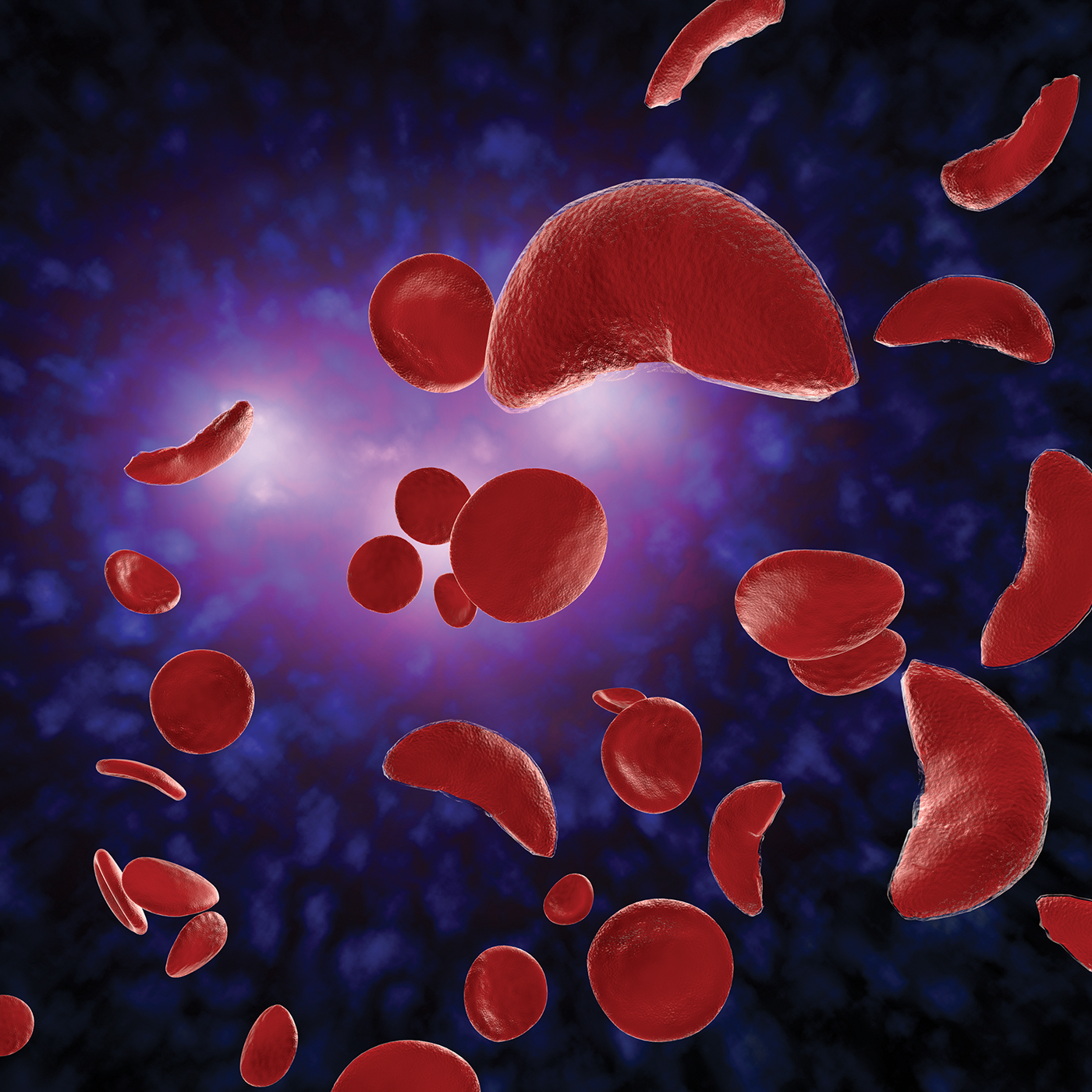

In December, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved two gene therapies for sickle cell disease, a life-shortening blood disorder caused by a single mutated gene.

The therapies have all the symptoms of miracle cures. They halt the mutation that deforms red blood cells, which results in inflammation and organ damage. They eliminate the need for daily medications. They bypass a hurdle of bone marrow transplants, which require hard-to-find donor matches.

“This is a dream come true,” says Martin Safo, Ph.D., a professor at the VCU School of Pharmacy who has researched sickle cell disease for three decades. “When I started, my mentor and I, this is all we talked about — that one day there’s going to be a gene therapy to treat this disease.

“But the question is the impact. Will this help millions of sickle cell patients all over the world? And my answer is: The impact is going to be minimal for the foreseeable future.”

The new therapies — Casgevy (which uses CRISPR, a gene editing tool, to alter DNA) and Lyfgenia (which adds a good hemoglobin gene to a patient’s DNA) — offer hope for the 100,000 Americans living with sickle cell disease. But for most, hope is all they currently offer.

These marvels of medical science cost millions and are procedurally arduous. Only a few dozen medical centers are authorized to provide them.

“It’s a transformative therapy,” says Wally Smith, M.D., director of VCU’s adult sickle cell program. “But we will have to screen 1,200 adults to get, I’m guessing, 15 to 20 patients who get it.”

The therapies work by extracting blood stem cells — the cells from which all others “stem” — out of bone marrow, then engineering around the sickle cell mutation. The stem cells are reimplanted after the patient undergoes chemotherapy, which destroys the diseased blood cells and allows the rehabbed stem cells to produce healthy cells in their place.

The few centers that can do this (including VCU, which is a Lyfgenia trial site) will only be able to treat a handful of patients to start, Smith says. The monthslong procedures require extended hospital stays. They don’t repair the organ damage or chronic pain a patient might already have.

“For some, I think the hard reality would be ‘I already have such bad organ damage, and I’m 50. Is it worth risking my life urgently with chemo in order to try to stop the damage from progressing? Or should I live out the rest of my years, use [daily medication] and do the best I can?’” Smith says.

“I think if I were in that situation, I’d think long and hard before I said yes.”

But back to that hope. Even though the new therapies are out of reach for many, it might not always be that way.

The aforementioned bone marrow transplant also involves collecting and infusing stem cells. It was a mid-20th century creation that won its performing physician a Nobel Prize. Today, more than 9,000 such transplants are performed in the U.S. annually, according to data from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration.

The patient pool will also undoubtedly increase, says Beth Krieger, M.D. (H.S.’20), who specializes in cellular therapies at Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU. The FDA estimates 20,000 Americans — those who are 12 and older and experience repeated pain — are currently eligible for the therapies. But they are also being tested in younger children.

With early treatment, they could be spared sickle cell’s worst effects, Kreiger says. U.S. patients typically live only to their early 50s, and more than half are insured through Medicaid, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Those with private insurance spend an average of $1.7 million in their lifetimes on medications, according to the American Society of Hematology.

We spoke with Krieger, Safo and Smith about these dream treatments, their possibilities and limitations. Their quotes have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Living disease-free

Beth Kreiger, M.D., pediatric hematologist-oncologist

I absolutely think gene editing or gene addition is going to change the way we treat sickle cell. I treat patients when they’re young, and my hope is that, moving forward, we can cure their sickle cell before their bodies develop many of the complications that come with the disease — especially to the kidneys, lungs and other organs.

There are advantages and disadvantages to a pill you take daily, especially when you’re talking about treating for a whole lifetime. It manages your symptoms and keeps you living. But how much does it cost? How does it make you feel? Many adults would take a pill every day without issues, but we know that young adults and teens have a hard time taking daily pills.

A big hurdle we’ll have to get over is how to offer gene therapy to as many patients as we can. How will insurance, and particularly Medicaid, help us offer this? And right now we’re using the same medical requirements as the clinical trials, so patients with milder sickle cell, patients under 12 and patients who have had strokes are locked out. I think we’ll be able to change some of those guidelines.

There will always be patients who choose not to partake in this therapy, so we definitely need to offer other therapies, too. And not every medical center that treats sickle cell patients has an active gene therapy or cellular therapy program, so figuring out how to connect to existing systems — or develop their own — is something medical centers are going to have to work through.

‘It’s not going to be accessible’

Martin Safo, Ph.D., professor and sickle cell researcher

The most important roadblock for gene therapy is it’s not going to be accessible to millions of people — in Africa, for instance. You have about 20 million people worldwide suffering from this disease. Most cannot afford a $2 [million] to $3 million cure. I mean, it’s not going to work. It’s very good for industrial countries, like the U.S. and in the European Union. But even then, there are many patients who might not want it.

Beyond gene therapy and transplants, there are five approved drugs to treat sickle cell disease. All have a modest impact on the disease process, and patients still suffer from severe complications. That’s one reason why our focus has been to seek an affordable “functional cure.” Our drug, ILX-002, is currently in preclinical studies; we’re planning early human trials in 2025.

The drug targets the primary disease process by blocking the aggregation of the sickle hemoglobin. Once you block that, you prevent the downstream effects — anemia, loss of hemoglobin, inflammation, organ damage. You end up with a very benign disease.

This is going to be a once-daily pill. And it’s going to be relatively cheap; the compound is easy to make. We believe it will be the holy grail for sickle cell disease. Gene therapy is very expensive. It’s going to be difficult to make it cheaper. And you’re talking about a lot of very poor people.

A boost in awareness

Wally Smith, M.D., director, VCU adult sickle cell program

I have a lot more enthusiasm for the masses getting a disease-modifier therapy like what Martin is working on. But I am not against gene therapy for those who can afford it. And I would fight for it for my own daughter or son, absolutely.

So we have to work hard now to get these new therapies to patients. And I don’t believe we’re going to be able to get it to more than five people in the state, maybe 10, in the next year. And if we get 10, I’ll be doing backflips because the infrastructure to treat one patient is extraordinary. I think that’s the problem of scale that will remain with us for the near future.

The uninformed citizen views this as a headline: A disease for which there was no cure now has a cure. The truth is we need to bring along both disease modifiers and transformative therapies. My fear is that somebody will come along and say, “We don’t need to do any more. We have a cure. Job done. Next.”

Finding something for those who can’t get gene therapy is important. This news wakes people up. That is actually the thing I’m most enthusiastic about: the awareness this has raised in patients. Now they come see us and say, “I want gene therapy.” And you go, “It’s not that easy. But wait, I have six other treatments I’d like to talk to you about — other drugs, bone marrow transplantation, major clinical trials. Here are all the other things that can still make your life better.”