Politics & Government

Behind closed doors: Virginia’s eviction epidemic

After a landmark study shined a light on the breadth of eviction proceedings across parts of the country — and turned the nation’s eyes to Virginia — VCU’s RVA Eviction Lab has become crucial to defining the problem and trying to fix it.

The headline, in April 2018, arrived above the fold on the front page of the Sunday New York Times, with a Richmond dateline. Locally, the news might as well have been fired out of a cannon.

“Everybody was shocked,” says Christie Marra, the director of housing advocacy at the Virginia Poverty Law Center.

Well, almost everybody.

The article outlined a first-of-its-kind analysis by researchers at Princeton University that measured eviction in the U.S. from 2000 to 2016 through court filings and judgments, and the findings were not good — particularly in Virginia.

Among the large cities included in the Princeton study of 83 million court records, half of the top 10 for judgments granting an eviction were in Virginia, with Richmond, Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk and Chesapeake holding positions 2, 3, 4, 6 and 10. Virginia also had an unfortunately strong showing among midsize cities, with Petersburg, Hopewell and Portsmouth at Nos. 2, 4 and 5.

In Richmond, the 2016 eviction judgment rate of 9.1% (a revised estimate, down from the 11.4% the lab originally reported) meant that 1 in 11 renter households had faced imminent, court-sanctioned eviction. That was more than twice the statewide rate (4.1%) and nearly five times the national average (1.9%). Worse still: 2016 wasn’t just a bad year. The data had been similar, or worse, for years.

Across Virginia, where around one-third of the state’s 3 million housing units were occupied by renters, more than 90,000 renter households faced the formal threat of eviction in 2016, some of them multiple times, with 144,000 eviction filings made in court seeking to remove them.

But, Marra says, the state’s statistics were no surprise to attorneys like her and others working at legal aid and housing advocacy groups. The reality was “you’re going to see at least one client coming in with an eviction case a week, maybe a day, maybe an hour, depending on where you are,” she says.

One revelation, though, did deliver a jolt: “We knew it was bad,” she says. “We just didn’t know that we were so much worse than everywhere else.”

Shortly after the news broke, Marra and others from advocacy and aid organizations gathered at a Southside Richmond brewery. “We gotta do something. What are we going to do?” she recalls as the tenor of the meeting — but not as it related to fighting evictions directly; that much they all were doing already. The question was how to “capitalize on this publicity, and get people — legislators, city council, whoever — to do something.”

Data had been powerful enough to breach the public consciousness, and would prove crucial going forward. Not long after the meeting, Ben Teresa, Ph.D., and Kathryn Howell, Ph.D., professors in VCU’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, began helping Marra and the others parse the Princeton findings. By late summer 2018, Teresa and Howell realized there was an appetite for a more formal structure that could bring in grants, partnerships and student researchers.

Six years after their RVA Eviction Lab took shape and set off into the chasm blown open by Princeton, the lab’s research and analysis now feeds the discussion in state government and street-level organizations. It has become both a telescope and a magnifying glass through which eviction’s reach across the state is understood, from the spread of its vines to the knots they form.

The lab has shown, for instance, that the Richmond neighborhoods with the highest average eviction judgment rates from 2000 to 2016 — including an area in Northside near Battery Park that in 2016 had a rate of 76% — are not actually the most impoverished parts of the city. It turns out that one of the most significant predictors of eviction in Richmond is, more than income or property value, the racial makeup of a neighborhood. As the Black population increases, so does eviction.

As an increasingly detailed picture has emerged of who faces eviction and why, and how to possibly alleviate its causes and effects, the lab more recently has turned its attention to the other side of the equation: Who is doing the evicting?

Ben Teresa, Ph.D., cofounded the RVA Eviction Lab in 2018. It since has become both a telescope and a magnifying glass through which eviction’s reach across Virginia is understood. (Jud Froelich)

“This is the question,” Teresa says when the question surfaces half an hour into a conversation this past summer.

As journalists’ questions go, it’s a pretty basic one: “Could we take a minute to just define ‘eviction?’” The thing is, scratching the surface even a little reveals there’s more to this than a pile of personal effects on the curb.

“A lot of people don’t see this issue, and they don’t understand the depths of the issue,” says Howell, who is now director of the University of Maryland’s National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education and remains affiliated with the RVA Eviction Lab. “I think anybody involved in this work has had [the conversation] with their family at some point, or their friends, or somebody at the bar who’s like, ‘Oh, you do eviction work. Well, people should just pay their rent.’”

“Well, sometimes they do,” she tells them. “But there’s a larger conversation to be had here.”

That narrow understanding makes some sense given the relative lack of data before the Princeton findings were released. There was no comprehensive tracking of the issue, by the government or otherwise; in 2003, the authors of a scholarly article in the journal Housing Policy Debate referred to eviction as a “vast, hidden housing problem,” and 15 years later that was still the case. The person behind the Princeton effort, sociologist and MacArthur “genius” grantee Matthew Desmond, Ph.D., had primed the nation’s interest in 2016 with his bestselling book, “Evicted,” a close-up look at the issue in Milwaukee that won a Pulitzer Prize the following year. Speaking in 2019 to VCU students who’d read the book for the university’s Common Book program, Desmond described his team’s work as “literally taking an invisible problem and trying to put it on the map.”

In that way, Howell says, the eviction issue invites a parallel to the foreclosure crisis of a decade-and-a-half ago: a raging storm the nation tried to understand only after it was already engulfed by it.

At its core, eviction is a civil legal process, most often set in motion over nonpayment of rent. In Virginia, a landlord first gives a written warning; if the payment isn’t made within a legally set time frame (typically five days), the landlord can file for eviction in court. The tenant receives what’s called a summons for unlawful detainer and a court date. In 2023, this happened around 146,500 times.

Of the tenants who go to court, few have the benefit of an attorney as only criminal defendants have a right to counsel in Virginia. From October through December 2023, the most recent quarterly RVA Eviction Lab analysis shows the median percentage of tenants with legal representation (in jurisdictions with 20 or more filings for the quarter) was 0.2%. In all of 2022, that figure was 1.6% for Virginia tenants and 71% for landlords, according to the congressionally created and funded Legal Services Corp., which operates independently and is the entity from which the eviction lab pulls much of its raw data.

And the court proceedings can move swiftly. In 2021, after observing about 550 cases in courtrooms in Richmond, Newport News and Alexandria, the lab found that 86% of the hearings were finished in less than five minutes; more than 40% lasted fewer than 60 seconds.

In part that’s because many tenants don’t show up, despite the opportunity to mount a defense or to be connected with aid groups that might help broker a deal with their landlord. Sometimes, Howell says, defendants don’t realize they need to attend, or they might not want to miss work, especially if an eviction seems inevitable. As a result, statewide last fall, 67% of all court victories for landlords were won by default.

Last year the right to evict was granted in about 55,400 cases, more than a third of all cases filed. When that happens, short of a successful appeal, the landlord then decides whether and when to set the eviction process into motion. When they do, the local sheriff’s office schedules a date for people and belongings to be removed from the property.

Often, though, eviction judgments don’t reach such a high-visibility ending of someone’s possessions strewn in a yard and might not even result in an actual eviction. The Richmond City Sheriff’s Office says that in 2023 it carried out nearly 58% of the almost 4,900 evictions it had scheduled; the rest were canceled. Sometimes the tenant can catch up on payments and halt the process, or the parties reach another agreement. Other times they don’t, but the tenant clears out ahead of the sheriff’s arrival.

“Most families aren’t interested in that kind of humiliation,” Howell says. Belongings are liable to be damaged or lost outside, and “you can imagine what that [experience] is for your kids, for yourself, for your job, your standing in the community.”

Still, the court and sheriff statistics capture only part of the picture. Households evicted through the legal process are the readily countable ones, Teresa says, and he estimates they’re a “fraction of a larger universe of forced moves.” That might include people squeezed out by double-digit rent increases; landlords deciding not to renew a lease, or even unlawfully changing the locks; or tenants figuring they’re headed for an eviction and leaving to avoid interaction with the justice system.

Those moves can carry similar downstream effects. “Losing your home is incredibly destabilizing for health, for finances, for children,” Teresa says. “It destabilizes not only the household, but the wider neighborhood and community.”

And many tenants then land in more challenging circumstances, Howell says. “It could be that they’re doubling up with family, they’re living in their cars, they’re in some cases obviously moving into a shelter or onto the street, or moving into a much poorer-quality apartment that is not so particular about eviction filings.”

“WE MIGHT THINK OF THE CAUSE OF AN EVICTION — THIS UNPAID [RENTAL] DEBT — AS A PRIVATE DEBT. BUT REALLY WHAT HAPPENS IN AN EVICTION IS THAT SO-CALLED PRIVATE DEBT REALLY TURNS INTO A CASCADE OF PUBLIC EXPENSES.”

That leniency was relevant because, until recently, eviction filings could linger for years on Virginia court records — and therefore possibly in the background checks of potential renters — even if the landlord ultimately lost or dropped their lawsuit.

That has changed in recent years, and now tenants can — after a month if an eviction case is dismissed by the judge, or six months if it is dropped by the plaintiff — submit a form to the state Supreme Court to have a hollow eviction filing wiped from their record.

It was part of a three-year burst of legislative resolve after The New York Times article, which resulted in more than two dozen new state laws that began to recalibrate a system that Martin Wegbreit, the recently retired litigation director at the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society, called “an unforgiving rush to judgment” in a 2023 article digesting the revisions in the Richmond Public Interest Law Review.

Among other changes, lawmakers: required that leases be put in writing; established a cap on late fees; extended the window for a tenant to catch up on payments to halt an eviction, which now can be done until 48 hours before the sheriff’s arrival; tightened the time frame to six months (down from a year) in which a landlord could initiate an eviction after receiving the go-ahead from a court; required landlords to provide tenants a state-issued list of their rights and responsibilities that must be signed by all parties in order for the landlord to be able bring a lawsuit later; and created stiff fines for landlords who carry out extrajudicial, DIY evictions. During the thick of the pandemic, landlords were required to use Virginia’s COVID-19 rent relief program before filing for eviction over unpaid rent, and owners of five or more rental units had to offer catch-up payment plans in an effort to keep people housed.

“Virginia made some really important decisions after 2018” in the General Assembly and at agencies like the Department of Housing and Community Development, Howell says, which, in turn, allowed the state to move quickly against housing pressures that arose during COVID. “I can’t imagine how many more families would’ve been unhoused or otherwise housing-unstable throughout COVID but for the work that they did to get money out the door.”

Still, Marra, of the Virginia Poverty Law Center, says, “I think we have a hell of a lot of work to do.”

Tenants and advocates continue to push for laws that would, for instance, limit rent increases; block landlords from evicting people from homes that aren’t up to code; and give tenants 14 days to make a late payment before an eviction is filed, rather than the typical five-day period. “Having those extra nine days means you get another paycheck,” Marra says. “Who gets paid every five days?”

Expanding the right-to-counsel guarantee to eviction cases is also a top priority. As an attorney, Marra says she imagines the court experience for a tenant representing themselves “would be like me walking into an operating room and being expected to help with the procedure.”

In March, the RVA Eviction Lab released an analysis of the potential costs — those spent and saved — of providing the service in Richmond, even if on a limited scale. It estimates that every dollar spent to provide an attorney would result in at least $2 saved.

“We might think of the cause of an eviction — this unpaid [rental] debt — as a private debt,” Teresa says. “But really what happens in an eviction is that so-called private debt really turns into a cascade of public expenses,” from the costs of emergency shelter and foster care to hospital visits and downstream law-enforcement costs.

VCU history alum Jamesa Parker (B.A.’15), now an attorney with the Legal Aid Society of Eastern Virginia, says she finds that people facing eviction or hoping to fight one often aren’t fully aware of their rights. (Jud Froelich)

Jamesa Parker (B.A.’15), an attorney with the Legal Aid Society of Eastern Virginia, sets up weekly at a public library to see walk-ins seeking legal help. She shows up at public meetings. She knocks on doors at apartment complexes, using data compiled by the eviction lab as a guide.

Often what she finds is that people who might be facing eviction, or who are hoping to fight one, aren’t fully aware of their rights or the intricacies of the rules. “You literally have to either know something [about it] or know enough to contact us … so we can provide you with that knowledge and help you through that process,” she says.

Parker has been with the organization for five years. Over the past year or so, through a fellowship with Equal Justice Works, she’s tightened her focus to housing issues, and particularly subsidized housing, in the East End of Newport News and an adjacent area of Hampton, near the tip of the peninsula where the James River meets the Chesapeake Bay.

At one of the buildings she canvasses, Parker has seen and heard about issues with mold, gaps at the foot of doors that let in “snakes and mice and all types of things,” gas stoves that have caused fires or with starters that click even when not in use, and water leaks. At one apartment, it was “basically raining in their bathroom from their upstairs neighbor flushing their toilet and doing their laundry.”

When tenants call their landlord to request a repair and nothing happens, they sometimes dig in with what seems like their only ace: withholding rent. But that just exposes them to a possible eviction. “It can be difficult, because you feel for the tenants,” Parker says. “I don’t want you living in these conditions. It’s not right that you’re living like this, or subjected to this treatment.” But she says the law is clear: Tenants cannot withhold rent in Virginia. And if they abruptly move instead, they could be held liable for breaking their lease.

There are only two legal paths to pursue a fix, and both begin exclusively with making a request in writing. If repairs aren’t made, one option — available only to tenants who are current on their rent — is to sue the landlord, in which case the tenant still pays rent but it’s held temporarily by the court. (However, tenants won less than 15% of the 1,750 such cases they brought to court statewide from 2017 through 2019, according to the RVA Eviction Lab.)

In 2020, a second path was created: After 14 days, tenants can hire a licensed contractor to make repairs of up to $1,500 or one month’s rent, whichever is greater, that can be deducted from the rent with an itemized receipt, even if the work was done for free. Typically, though, Parker says, “our clients don’t have that type of money sitting around.”

Even renters more familiar with the law can get caught up in an eviction and its aftermath.

“I generally describe my role as the bridge between the legal community and the residential community,” says Omari Al-Qadaffi (B.S.’06), a housing organizer in Richmond for the Legal Aid Justice Center. He has been at the organization since 2019, and in that time he’s been a fiery and effective advocate whose work has been recognized nationally by the National Housing Law Project.

He’s also, at times, been on shaky footing with his own housing, stemming from an eviction in 2017.

Al-Qadaffi’s VCU degree is in computer science, and he was working in software programming until 2012, when he found himself feeling disconnected, “like I wasn’t contributing to making the world a better place, and wasn’t more in touch with my family and my children.” He left that job and, around 2015, began to lean toward advocacy. At the time, he was renting in a building in Richmond’s East End, a “legal nerd, even back then,” living in what he describes as an “eviction mill.”

“I just could see that my neighbors didn’t know their rights, so I just started canvassing the neighborhood and doing a lot of work there,” including pushing back against an effort to remove a bus stop outside the building.

Then, he says, he got into a dispute with the building’s management over a penalty for a late payment, which triggered not just a late fee but effectively a rent increase, nullifying a deal of lower rent in exchange for signing a longer, 18-month lease. It was something he’d seen happen with other tenants, Al-Qadaffi says. When he refused to pay the higher rent, the landlord filed for eviction; this happened three times, Al-Qadaffi says. Each time, appearing in court without representation, he would lose the case and then appeal; each time the landlord dropped the suit. Al-Qadaffi isn’t sure why.

“But they ended up winning in the end,” he says. A fourth eviction suit was filed and Al-Qadaffi says he called the court and “told them I was running a little late, and they said ‘OK,’” but then issued a judgment in favor of the landlord. This time, Al-Qadaffi didn’t appeal.

At a few points over the next 3½ years, he dealt with some degree of housing instability — a mouse-filled rooming house in a gentrifying neighborhood, which the landlord wanted to sell shortly after the pandemic started; a roommate situation that didn’t work out; a week without a home at all, during which he stayed on a family member’s couch — before he found his current home in the summer of 2021.

“It was damn near a miracle that I got into this place,” Al-Qadaffi says, “because I know my credit wasn’t that great, and I had the eviction on my record.”

The notion that he was a well-regarded housing advocate without stable housing was a painful irony and a reflection of a wider reality. And since the pandemic subsided, Al-Qadaffi says he’s noticed that tenants seem more hesitant to raise issues with landlords.

“They don’t want to ruffle the feathers right now because of the housing market. [Landlords] could easily put them out and charge somebody else a couple hundred dollars more in rent,” he says. “I work with lawyers and I help people fight for their rights every day, and when my mother says, ‘Well, I’ve got a good deal over here with my rent, so I don’t want to press [the landlord] too bad about the leaking roof … because I don’t want her to raise my rent,’ I’m thinking in my head, That’s valid. I can’t do anything for you, because they really could.”

Omari Al-Qadaffi (B.S.’06), a housing organizer in Richmond for the Legal Aid Justice Center. “I generally describe my role as the bridge between the legal community and the residential community.” (Jud Froelich)

Where legislative efforts leave off, data may be providing tenants some defense.

The RVA Eviction Lab’s most useful tool over the past year and a half is perhaps one that takes a piece of the tenant-landlord power dynamic and “turns it on its head,” Teresa says. If landlords can check whether a prospective tenant has wrestled with eviction, then tenants might be interested to see how much evicting a landlord has attempted.

“We would routinely get asked from our [community] partners … ‘Can you tell me about this owner? What are their eviction patterns like? Do they own other properties?’” Teresa says. So in late 2022, the lab, along with The Equity Center at the University of Virginia, launched the Virginia Evictors Catalog, a digital aggregation of eviction filing and judgment statistics that’s searchable and sortable by plaintiff — in this case, the management company or owner — by defendant’s ZIP code (but not by name), court jurisdiction, month or year and other details.

“Landlords talk a lot about the risks that they have to rent to somebody who’s got an eviction on their record,” Howell says. “We don’t talk about the risks that tenants have of renting from a landlord with a long history of high rates of eviction. … It doesn’t make sense from a public policy perspective or from a family perspective to place somebody in a building where 40% of the tenants get evicted every year.”

The data is publicly available through the state court system, though some say not in a user-friendly form. “The way that the records are presented [when searching a landlord], you don’t get a total count, you can’t really filter or sort the data, even by something as simple as date,” says Kathryn Dooley, a community organizing research associate with civic advocacy group New Virginia Majority. “So you’re just kind of stepping into a sea of information. … There needed to be some way of taking that data and making it usable, and that’s what the eviction lab data does really well.”

At the Chesapeake-based regional housing nonprofit ForKids, Jordan Crouthamel says the lab’s database “has been totally crucial to us.”

Crouthamel manages the organization’s eviction intervention program that was created with funding from the state’s Virginia Eviction Reduction Pilot program. “We can’t just expect folks to find us,” he says, so the apartment-building-level data has allowed the group to jump that barrier. The Evictors Catalog has been “probably the best community resource for figuring out how we can target assistance. So we really focus in on using that data to figure out who needs our program … but also where are the [apartment] complexes that probably would be open to having some assistance, because those numbers come back on them as well.”

He has found openness among some building managers to having ForKids help resolve a brewing eviction with financial assistance or even a promissory note. “We’re trying to make both sides whole,” Crouthamel says. “As a landlord, as a property owner, you have financial realities that you have to face. Those mortgage payments still come [due].”

The program is now starting to get calls not just from tenants wanting to keep their apartments, he says, but also from landlords wanting to keep their tenants.

That’s the goal of most landlords, says Patrick McCloud, who helms the Virginia Apartment Management Association, which advocates for the state’s rental housing industry. The eviction process can mean a minimum of two to three months of lost revenue, he says. “The absolute last resort is an eviction.”

But he says the Evictors Catalog seems to exist solely to “shame landlords.”

“I don’t see the public service in pointing a finger [at], ‘Oh, this landlord did what they needed to do to ensure the contractual obligations were met.’”

Eviction is a necessary tool, he says. “As much as you don’t want to use it, it is something that allows you to take chances.” The harder the law makes it to evict, and the longer that timeline becomes, McCloud says, “less and less chances are going to be provided to people.” McCloud instead has called for long-term solutions to provide affordable housing and urged the state government to create rent relief and voucher programs to ease the strain on renters.

Those are solutions Teresa and Howell are agitating for, as well. But, Teresa says, “the question isn’t so much ‘What works?’ … it’s much more like: How do we develop the political will? How do we develop community capacity and advocacy and voice to bring that power to bear on city councils, state legislatures and so forth?

“LANDLORDS TALK A LOT ABOUT THE RISKS THAT THEY HAVE TO RENT TO SOMEBODY WHO’S GOT AN EVICTION ON THEIR RECORD. WE DON’T TALK ABOUT THE RISKS THAT TENANTS HAVE OF RENTING FROM A LANDLORD WITH A LONG HISTORY OF HIGH RATE S OF EVICTION.”

So the effort to illuminate and understand the current situation continues. And it’s moving into the role of larger companies.

Recently the RVA Eviction Lab added a column to the Virginia Evictors Catalog that counts serial filings — instances of a landlord filing for eviction against the same tenant more than once in a year. In Virginia, Teresa says the data suggests this happens on average to about 30% of the households that face eviction filings. Researchers elsewhere, he says, have found serial filings are most common among large corporate owners, for which business processes might be automated and the costs of filing for eviction — already comparatively low in Virginia — are more easily absorbed than for smaller landlords.

The idea, he says, isn’t actually to evict the tenant but to use the court case as a “debt-enforcement mechanism.”

The lab hasn’t yet studied the serial filing data across the catalog, but it has looked at serial filings in Richmond, Chesterfield County and Henrico County and found that from 2015 to 2019, 86% of the region’s more than 65,000 serial filings came from apartment buildings with 25 or more units.

These larger buildings accounted for about 69% of the region’s rental stock, and roughly similar percentages of its total eviction filings and judgments. But when lab researchers knit together the hundreds of smaller companies owned by larger parent companies, they found that two dozen companies were responsible for half of the more than 134,000 eviction filings against tenants in the region’s apartment complexes, and nine companies generated one-third of the eviction judgments.

Looking for those deeper levels of ownership is slow going — a mix of rooting through property records, state business filings and “old-fashioned Googling,” Teresa says — and it sometimes leads to a dead end. But the lab is writing a handbook to help groups that have asked how to do this kind of corporate genealogy. Teresa imagines a future version of the Evictors Catalog that would embed the data in a map; clicking on a building would show the eviction activity there, plus the other buildings under the same ownership. That might be a few years away, but already the team has built an early version of the portion that covers the city of Richmond and Chesterfield and Henrico counties.

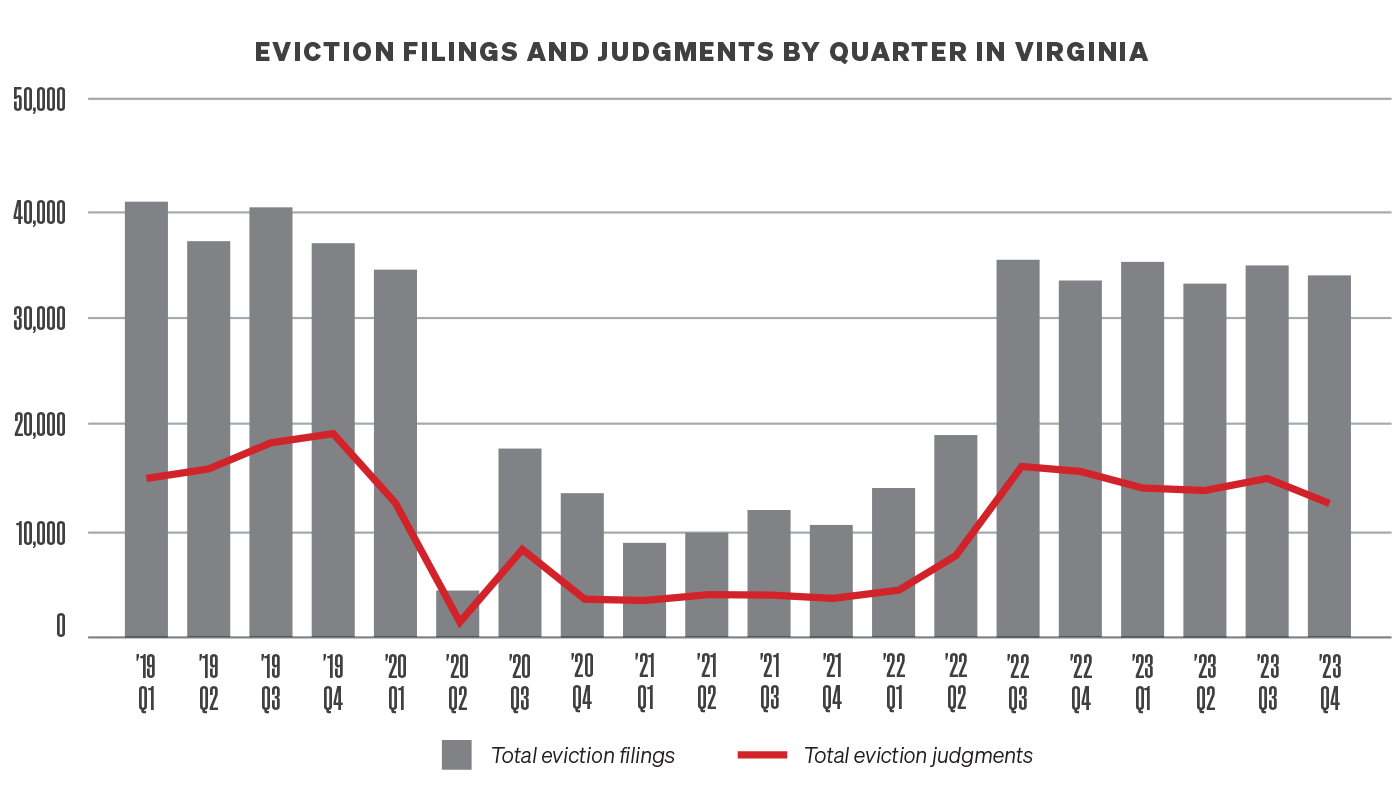

Statewide, eviction filings and judgments consistently hover below their 2019, pre-COVID benchmarks, although individual jurisdictions have breached their thresholds. For eviction filings, the state as a whole has remained at around 85-90% of its 2019 levels in each of the past six quarterly analyses from the RVA Eviction Lab, from mid-2022 through 2023.

In the meantime, the mounting data gives some contour to the present and a modicum of hopefulness, even if the horizon remains inscrutable.

Statewide, in total, eviction filings and judgments consistently hover below their 2019, pre-COVID benchmarks, although individual jurisdictions have breached their thresholds. For eviction filings, the state as a whole has remained at around 85-90% of its 2019 levels in each of the past six quarterly analyses from the RVA Eviction Lab, from mid-2022 through 2023.

Teresa also points to Princeton’s running tally — which stacks the past 12 months’ eviction-filing data for 10 states and nearly three dozen cities against their pre-COVID averages — that shows some locales tracking lower, including Virginia and Richmond, while others are higher.

In the moment, he wonders whether the state programs, the policy changes and the years of media and scholarly scrutiny may have eased the swelling, if only slightly. It’s too soon to know which forces are pulling down the numbers, or whether the trend will hold. Still, it’s reason enough for Teresa to wonder whether Virginia is no longer the outlier it once was.