Arts & Culture

Alexandra Mitchell’s bespoke profession

The arts alum made her name styling indie musicians boygenius and Father John Misty, designing layered looks with layered meanings — all while creating her own career that combines sourcing and styling: vintage fashion consultant. In this story and Q&A, Mitchell explains how.

I’m with vintage-fashion stylist Alexandra Mitchell (B.A.’16), watching a 2023 YouTube interview with an eccentric Canadian DJ.

“What you have on now is amazing. Could you explain what’s going on here?” he says to the members of supergroup boygenius, waving the microphone in front of rockers Julien Baker, Phoebe Bridgers and Richmond’s own Lucy Dacus, each wearing a black bomber jacket customized with sewn- and pinned-on patches.

The mic finds Dacus.

“I have a friend from high school, Alexandra Mitchell, who has always been like this,” she says. “Always decorating her walls with a bunch of stuff, cutting stuff out of magazines and collecting things.”

For 30 seconds in this 34-minute interview, Dacus talks about the jackets and patches. They’re Mitchell’s idea. She sourced each patch, scouring the internet, boutiques and thrift stores to find images that represent each singer-songwriter’s lyrical contributions to the band’s Grammy-winning 2023 album, “The Record.”

“[She said it] with my full government name,” Mitchell says with a burst of laughter as we sit outside a cafe near her Shockoe Bottom [Richmond] apartment on a gray fall day. “And I was like, ‘No! Don’t call me your friend! Call me the very professional, real adult who has a job!’”

It’s actually more of a lifestyle.

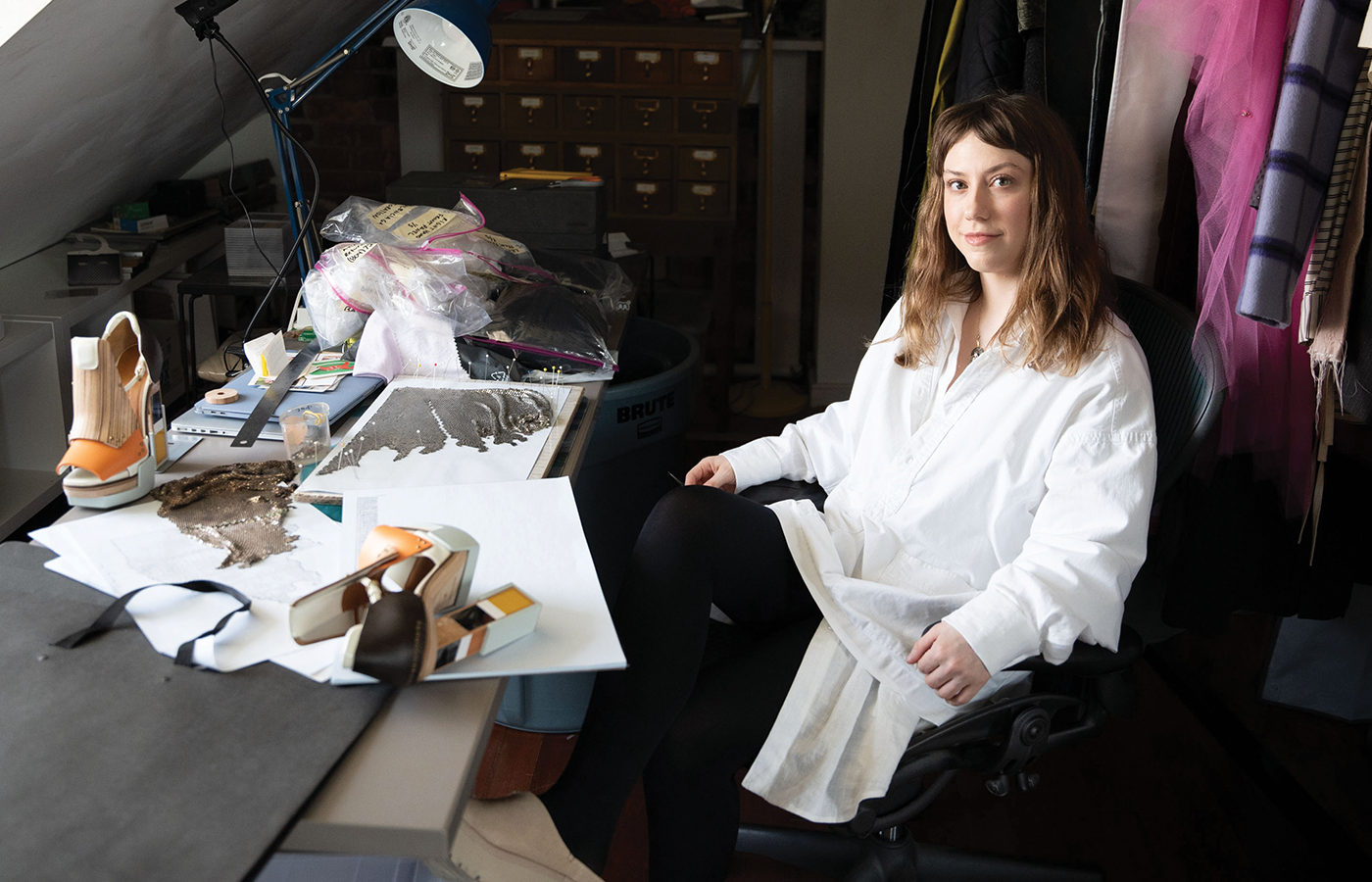

Alexandra Mitchell at her desk in her Shockoe Bottom apartment. (Jud Froelich)

Mitchell has been telling visual stories from her earliest days. As a 5-year-old, she asked her mom to sew clothes for her Barbies, and now she’s showing me the range of vintage fashion pieces that make up the mood boards she creates for artists and brands. Her full job title is probably something like freelance vintage styling consultant and historian. And it’s a profession she is, more or less, trying to create.

“A little bit,” Mitchell says. “I’ve done some traditional styling work, but the jobs I’ve been most excited [about] are more collaborative, where I’m working with a stylist and saying, ‘Here’s how to bring more interesting designs into your concept, and I can get them for you.’ The thing that’s difficult — in addition to knowing what you want — is vintage-on-demand is not a thing. If someone wants a really specific Comme des Garçons piece or Yohji Yamamoto or whatever, good luck going out and making it just appear. [You need to have] relationships with many, many, many vintage dealers all over the world and knowing who would have this or who would know where to get this, and kind of liaising behind the scenes to source.”

Initially self-taught, Mitchell developed her “literacy of design” by consuming a lot of images in fashion magazines, contemporary and past, and through Pinterest and Tumblr. She’s spent years assembling on a budget a 200-piece collection of vintage Balenciaga, a seminal luxury fashion line founded in Paris in 1919 and renowned for its quality and timelessness.

Mitchell specializes in finding “ultimate grail vintage pieces,” a skill honed professionally at the small vintage fashion company Byronesque in New York, where she worked after college, then at The RealReal, the biggest online platform for authenticated luxury and designer resale, where she learned to authenticate and price vintage clothing and accessories.

Mitchell got her first professional break in 2014 when designer Christian Francis Roth followed a Pinterest board she made of his work (those Pinterest boards can be considered a forerunner to the mood and vision boards Mitchell uses today to communicate with clients). Sensing an opportunity, Mitchell messaged him. After some back and forth, Roth hired Mitchell to help him digitize his archives — press clippings, film slides, VHS tapes — and run a blog featuring those archives.

“I was very avidly using Pinterest at that time to organize and store fashion images,” Mitchell says. “I made a big board of his designs, and he messaged me, like, ‘Oh, my God, this is amazing,’ and so then I started interning for him and digitizing his archives and stuff. He actually got in his car and drove down all these boxes of all of his clippings and slides of all of his runway shows.”

Mitchell shows pieces from her extensive collection of vintage Balenciaga clothing. (Jud Froelich)

In 2020, Mitchell started styling her longtime friend Dacus for magazine shoots at DIY, GoldFlakePaint, Teeth, The Forty-Five and W and then her appearances on “The Tonight Show” and “Jimmy Kimmel Live!”

“It was a really particular moment that it all started happening because I was between jobs,” Mitchell says, “and she started getting all this press and she needed the help. At the time, there was no budget, and it was, ‘We’re both doing it because we’re both benefiting from working together.’”

Mitchell, who worked on a Disney/Marvel-McDonald’s collaboration to promote season 2 of “Loki,” has gone on to serve as an eye for style behind some of the biggest acts in indie rock today: Father John Misty (on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert”), Caroline Polachek and, of course, boygenius.

She does it by sourcing any item that could be a nod to the past or serve as a wink to fans, like those bomber jacket patches, which have become a thing among boygenius devotees. A week after our cafe interview, Mitchell texted me that she had just walked out of an October 2023 boygenius show in New York to find a group of fans wearing their own patch jackets.

“It’s a shorthand. It’s almost like an elevator pitch for someone who’s first coming into contact with the music and the band, right?” Mitchell says. “It’s like, ‘How do we communicate what we’re about?’ I think that’s true of anyone [and] how they get dressed. It’s like, ‘How do you capture people’s attention and communicate a lot very quickly?’

“I want to create very layered images. It’s so easy to scroll past everything and just” — Mitchell snaps her fingers — “consume it in an instant. And I think it’s really special to create images that you can come back to and just look at for a long time.”

Eight months or so before boygenius played that New York show (the band sold out Madison Square Garden), they made the cover of Rolling Stone, styled in black suits that call back to Nirvana’s 1994 cover of the same magazine. The interior shots channel the grunge band’s gender-bending 1993 shoot with the now-defunct Mademoiselle magazine.

Those looks were Mitchell’s idea, too.

“When boygenius started working together, I shared an idea with Lucy of, ‘What if you guys were Nirvana?’” Mitchell says. “She was like, ‘Oh my God, we love that. That’s so funny.’ We didn’t talk about it for a long time. [About six months later], she reached out, saying that Rolling Stone was happening, and she said they wanted to use my idea.

“I loved boygenius’ original [2018] EP, and the cover was a reference to Crosby, Stills & Nash. I already had that in my brain — placing these women among the ranks of the male greats of the music world. It just felt right. I liked the idea of this band of men, who were known for drab grunge, to be dressed in a very colorful and feminine way. To put those looks on boygenius [a band of queer women] felt like a very natural extension of the same idea, that the femininity contrasted just as naturally as it did with Nirvana, despite boygenius being a band of women, not men.”

As the idea took shape, Mitchell suggested using some of the pieces that Nirvana wore during the Mademoiselle shoot.

“I did end up being able to get in contact with the designer who made those super colorful scarves that the band was wearing as skirts — Gene Meyer, who lives in Morocco now,” Mitchell says. “He sent some of the original scarves. He only produced them for a couple of years in the ’90s in Japan, so they’re pretty difficult to find.”

In this Q&A, assembled from multiple conversations over several months and edited for length and clarity, Mitchell explains her created profession, her fashion philosophy and how the past becomes real.

In February 2023, boygenius made the cover of Rolling Stone. In a callback, Alexandra Mitchell helped style the trio as Nirvana, referencing the grunge band’s cover look from a 1994 issue of the magazine. (Jud Froelich)

Define “vintage,” please.

Alexandra Mitchell: Colloquially, people say vintage is 20 years or older. It’s archival designs, it’s rare fashion that you can no longer just walk into a store and buy. Fashion comes out seasonally. The spring 2024 collections are in stores right now, but by next season those clothes will only exist in people’s private closets and collections and the secondary market, which is where I source everything. So, yeah, I’m a vintage specialist, which is kind of a catchall for sourcing, authenticating, pricing.

Thank you. Describe your profession.

AM: It’s complicated, because a lot of the consulting jobs I’ve been doing, I’ve been doing something that doesn’t really exist. I’m kind of trying to make it a thing, which is consulting for stylists. There are so many amazing stylists who have such a great visual eye and understand what’s going to look good on camera, how to make it look good, and they have these amazing relationships with contemporary brands and are able to work with them to pull the clothes. But because vintage is so big now, I think there’s more of an interest in that literacy I’ve been talking about that isn’t as intuitive or prevalent within styling.

I think stylists, historically, are really focused on what’s current and what’s really cutting-edge. They’re really versed in current trends, but I’m someone who can say, “I see the direction you’re headed. I see what style you’re trying to do. Here’s a way to make that more layered and interesting.” Like, if someone wanted to do a contemporary shoot that was really minimal and striking, and they wanted to feature designs from contemporary designers, they could break that up and add interest by maybe bringing in some vintage Geoffrey Beene designs from the ’80s or something, but this isn’t necessarily something the stylist knows or has access to.

So you don’t want to be a traditional stylist?

AM: I don’t want to be a traditional stylist. It’s a very particular job that exists and there’s a certain way you do it, and it’s a lot of liaising with brands and not a lot of — I don’t know, it’s just different when vintage is involved. The good stylists are pulling vintage from other rental archives in addition to pulling from brands, but they don’t necessarily have someone to have conversation with and figure out what direction they should go within vintage.

They can hire me so I can be like, “Oh, don’t do the Vivienne Westwood corset. Everybody’s worn the Vivienne Westwood corset already. Let’s do, like, wouldn’t it be so cool if you did Romeo Gigli instead?” Because nobody’s doing that yet — you know, help them evolve the direction they’re going, in an informed way.

How did you get this knowledge and these skills?

AM: Out of necessity, I guess I would say. I was very into fashion from a young age, and up through college my relationship with designer fashion was only through the internet and just looking at pictures and getting magazine back issues from thrift stores or eBay or whatever and looking at these older designs. And it wasn’t that they were old. What was interesting to me was just exploring the breadth of design that happens to go backwards in time as well as what’s currently out there. It’s a literacy, just like anything else.

But even if I went to vintage stores or designer consignment stores [in Richmond], I wasn’t likely to see the clothing that excited me from these old fashion [magazine photos], and I didn’t have the income to start playing around with buying vintage, so I got into eBay and all of the associated websites. So the necessity was: I have limited funds. I love fashion. I’ve spent all these years looking at these now-iconic-to-me images from, you know, back issues of Vogue. And being able to scour the internet and find them for not very much money became a game before it became more intentional and a job — eBay, Poshmark, Depop, The RealReal, Japanese auction sites.

What’s it like when you track down a piece?

AM: It feels like these are artifacts from these images. With Balenciaga, I got very excited when I first got to interact with the pieces because I could see what they are beyond [being vintage]. I got to actually see the fit and the cut and the design and the details, but the initial attraction was that they were artifacts from these images of constructed moments in time that never actually happened, because they’re completely synthetic, right? It’s weird when you think about it.

Like Kate Moss shot by Steven Meisel for Vogue Italia 1995 or whatever — it was like it happened, but also it didn’t happen. And also, it wasn’t necessarily exactly what people were wearing at the time. It was an idealized version — a designer’s spring 1995 collection was their proposal for what the modern woman should wear. It wasn’t necessarily a reflection of what people were wearing on the street.

These images are not a candid moment captured in time that feels authentic to what actually happened. There are these highly constructed moments designed to evoke strong emotions in people — to encourage them to buy — and they feel very powerful to me, and I’m very drawn to finding these artifacts from this depicted world. Like, wanting that world to be real. It feels more real and better than what’s actually real. It feels like a more authentic way to interact with something that is, or was, totally superficial.

How so?

AM: For me, I feel that things feel more legitimate or more real if they’re old. Have you noticed that maybe things that you didn’t like when you were younger have grown on you now that time has passed? Whether it’s music or movies or whatever — things that came out at that time and felt not legitimate, so there’s this nostalgia element. But I always think of it as there’s this primordial goo-soup of the past, and the things I liked and the things I didn’t like all become the same soup. Like, right now, I could be, “I hate that car. That’s an ugly car,” but in the future, I’ll be like, “I miss those cars,” and they’ll kind of exist alongside the cars I did like at the time in my mind. In some ways, I think time reveals what design has staying power and what doesn’t. But I think everything looks a little bit nicer after 20 years.

If I’m looking at an old fashion image, and I’m diving deeper into it, everything becomes more real. Like, I found that exact jacket that that model wore, and then touching it and seeing it and seeing the construction and the lining and the beautiful design, it becomes more real the closer I get to it.

How does this compare to your experience with everyday, regular clothes?

AM: With fast fashion, the closer I get to those clothes, the less real they feel. You can get a jacket that looks like a knockoff of something, and then the pockets don’t really work, and the proportions are off, and you open it up and there’s no lining, and it’s like something that looks like a jacket and isn’t a jacket. It’s like “essence of jacket.”

People used to make their own clothes. So much of design now is based on vintage and older than vintage. Fast fashion is like a poor replica. If I went to H&M and bought a bomber jacket that was supposed to look like an MA-1 [classic model from the 1950s], there would be all of these elements that were off. They were trying to signal details that once had function or meaning, and now don’t have any utility at all and aren’t replicated correctly. The inverse of that is these hyper-real designs that I hunt down from designers who make runway fashion.

Alexandra Mitchell sits in a 1970s Italian leather chair in her Shockoe Bottom house, under a print from a Balenciaga series by M/M Paris. The design duo created many of Balenciaga’s most iconic ad campaigns from the early 2000s. (Jud Froelich)

What about your personal style?

AM: I think the best thing I could do for myself is to stop buying things, clothes.

I wasn’t expecting that.

AM: I don’t know. I just feel like it destroys creativity. I want to stop buying clothes. I know how it sounds — I can’t do it. I love them too much. But I’m like, I want to. I feel like style is way more interesting when people spend more time with the clothes they have and work with those.

So you want a more limited palette?

AM: Yes, because, I mean, that’s when I got into collecting. I had limited funds. I had limited access. It was like manipulating what I was able to get, not that I have a ton of access now or anything. I feel like at least when it comes to how I’m dressing myself personally, there’s always this search for: What’s next? Not because I need something new, but because I think when it comes to personal style, you’re looking for yourself, if that makes sense. It’s like I’m trying to find my purest form of self-expression, and I keep thinking it’s going to be in a new object that I don’t have yet. It’s trying to grasp for this continual improvement and self-expression, but I feel like the worst thing I could do is to continue to do that for my personal style, because it’s not true. It’s really about how you wear what you have, and that becoming the more true essence of your style.

How do you know when you have what you need?

AM: I think we just have to stop at some point. People are just more creative and unique when they’re working with what they have, in all contexts. And maybe that’s true on a bigger scale, too, with vintage. I don’t know how sad I would be if people stopped making new clothes. I feel like we have enough, and every crayon I could need in my box of crayons exists already.

Culturally, why do you think vintage is so appealing?

AM: I feel like there’s just a really intense, overall dissatisfaction with the present for everybody. I think that’s part of what fuels interest in things from the past. It’s “Everything must have been so much better before because things are so terrible now.”

But it’s complicated, because in some ways, like with fashion, things were literally better. Like, clothing was made better. But there’s also that draw: I feel closer to a different world. If I have these objects and I dress this way — this is so corny, but it feels like it’s meditative. It’s like positioning yourself in a certain way, putting on certain clothes, and it’s like willing yourself to be in a different reality, kind of. It sounds so pretentious.

Why do you say that?

AM: I don’t want people to think I’m trying to justify an interest, because I will willingly say, “I think this stuff is pretty, and I like it because it’s pretty.” But at the same time, there is this deeper motivation. I see a lot of people trying to justify their interest in fashion and intellectualizing it or comparing it to art or whatever because they’re embarrassed to be into clothes. So I never want to come off that way. It’s something that’s inherently superficial, right? It’s literally a facade, like the facade of a building, but on your body. So it’s interesting to try to convince people that there’s substance and merit there.

It’s very American to be extremely into self-presentation and how you look — I feel like we all are — and it’s very American to deny having any interest or concern with any of that. I grew up [in Richmond] going to punk shows with my friend’s older brother and trying to be cool and being so into music, and it felt like I was revealing something about myself if I made it about fashion. It took a while to really say, “No, this is what I want to do, and I’m just going to go in head-first.” I felt exposed by revealing to myself and others that I wanted to work in fashion.

One of the things with fashion in music is that, for so long, it’s been so many people who are trying so hard to make it look effortless. It’s not. I feel like I’m finally committing to the fact that I will never be irreverent. I’ve become very adamant about trying. It’s cool to try. It’s cool to put forth effort, and for that effort to be visible. It’s cool to care.