Research & Discovery

A royal statement

For the first time, a sitting British monarch acknowledged a link between the royal family and the slave trade. VCU professor Brooke Newman’s research is one reason why.

Brooke Newman, Ph.D., has spent the past year collecting the pieces of her blown mind after her research, in investigative tandem with London’s Guardian newspaper, pried from the British monarchy an unprecedented acknowledgment of its nearly 300-year role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Perhaps the most damning evidence the VCU associate professor of history found in the United Kingdom’s National Archives is a 1689 manuscript that records King William III accepting a thousand shares of stock in an enslaving company.

“The Guardian submitted select aspects of my research on the monarchy's links to slavery [to Buckingham Palace for a comment] but also the manuscript picture,” says Newman, who for nearly a decade has researched the monarchy’s central ties to the buying, shipping and selling of African people. “And they were like, ‘Wow, we can’t really refute this.’”

On April 6, 2023, King Charles III ended 70 years of royal hedging on the matter. Through a spokesperson, Charles said he supports research into the monarchy’s links to the slave trade, which begin with a broke Queen Elizabeth I trying to undermine Spanish geopolitical dominance of 16th-century Europe.

Under Charles’ mother, Elizabeth II, the palace line was something akin to “We regret the error” — but less assertive and undergirded by the immortal terror of being sued.

“Since the 19th century, they’ve been making ‘statements of regret,’ and that is the official phraseology for what they’ve been doing,” Newman says. “They’ve been saying, ‘It’s too bad this happened, and it was an atrocity, and it shouldn’t have happened, so we’re regretful but we’re not sorry,’ because ‘sorry’ suggests that you did something wrong, and we need to have a conversation about restitution and what that might entail.”

This surprising mote of thin candor is a very large deal.

“You have a family that is essentially a corporation,” Newman says of the British monarchy. “They have so much money. They have so much land. They have their hands in pies all over the world, and they have an opportunity to address something that no one has talked about, that Elizabeth II didn’t want to talk about, that, essentially, hasn’t been taught in schools, that wasn’t taught to people who were affected by this.”

Brooke Newman, Ph.D. “The monarchy is about appearing timeless, and the only way that they change is if there’s overwhelming societal pressure,” she says. (Jud Froelich)

The Windsors’ net worth is hard to calculate because it includes so much stuff (art, artifacts, jewels, real estate), but estimates put it at more than $34 billion.

“The Guardian told me that, in the past, whenever they shared forthcoming stories with the palace when Elizabeth was queen, there was never any comment, especially about past atrocities that made them look bad, particularly related to slavery or racial injustice,” Newman continues. “But Charles, through Buckingham Palace, did respond, and I think it’s because he was finally king and he felt the time was right to say something.”

The time is also why Newman’s once-niche research has gone mainstream. It’s another consequence of summer 2020, she theorizes, when outrage flared around the world over centuries of state-sponsored racial and wealth inequity and the many efforts not made to make amends.

In England, protesters tore down a statue of slave trader Edward Colston (1632-1721) and heaved it into a river. Colston’s the guy who gave King William III those thousand shares in 1689. A member of Parliament and a prolific philanthropist, Colston had been considered a national hero.

In Africa, the Caribbean and South Asia, the movement aimed its fury at the hangover of colonialism, in addition to slavery, both perpetrated in venal excess by the British Empire and to the benefit of the monarchy. For example, in South Africa, a former British colony, poverty is largely delineated by race, and much of the wealth still is controlled by British descendants.

The records Newman dredged from archives in England, including those at Windsor Castle, have always been there. It’s just that the few historians who read them viewed the documents as the boring accounting records they were meant to be. Slavery was a business venture and was documented as such.

“At least I can say, genuinely, that I think that I was one of the first historians to actually say: What was the monarchy’s role?” Newman says. “And how did it change over time? And why does it matter? And I think the question of why it matters has become really clear now.”

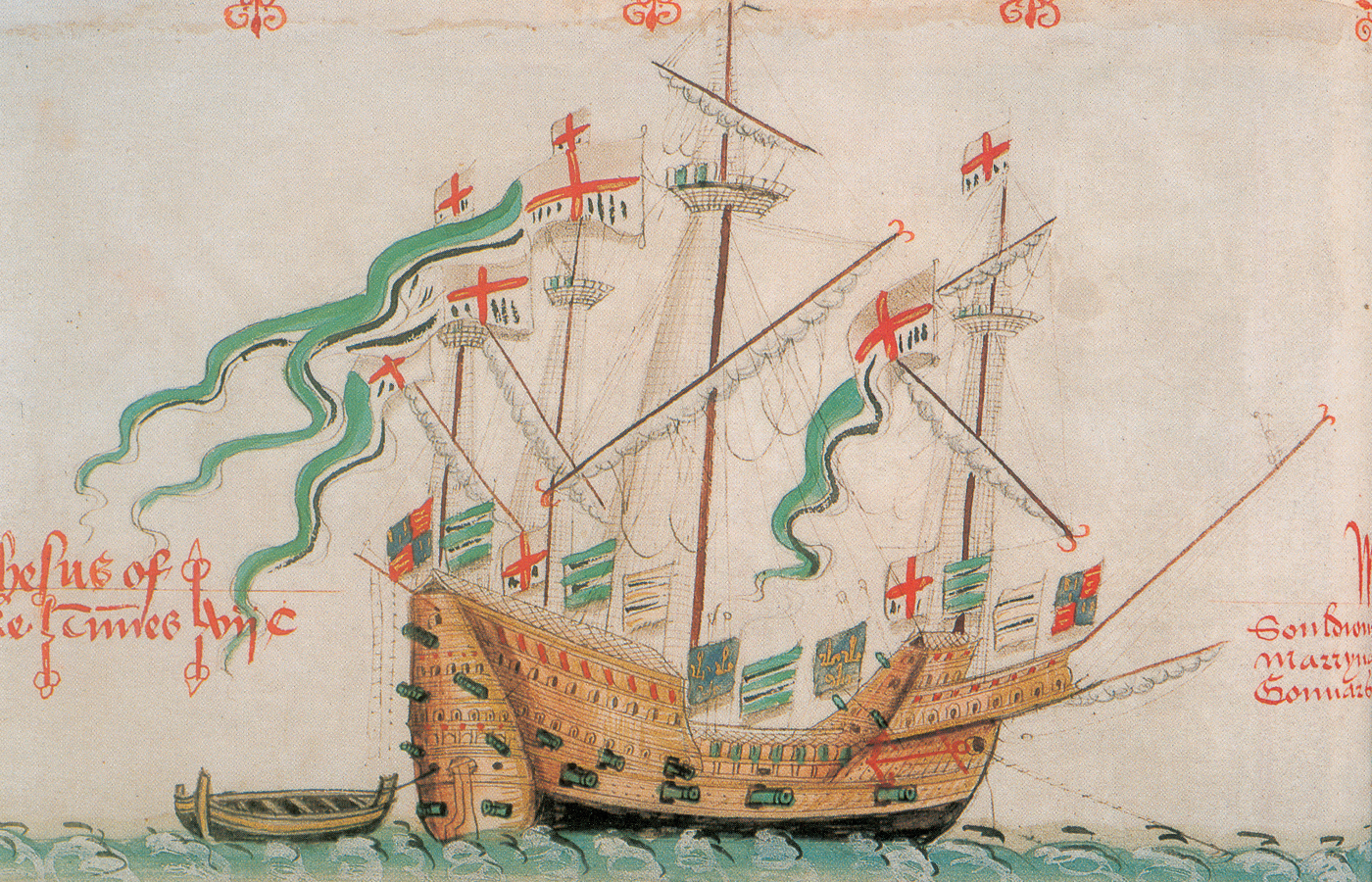

This 16th-century illustration depicts the Jesus of Lubeck, a ship used by Englishman John Hawkins to transport slaves in the mid-1500s.

The monarchy’s involvement in the slave trade dates to Elizabeth I and her 1560s sotto voce blessing of merchant and slaver John Hawkins, another former English hero facing a second opinion.

King Charles II formalized royal involvement about a hundred years later with charters for the Company of Royal Adventurers Into Africa and its successor, the Royal African Company, for which Colston served as deputy governor. Charles II’s younger brother, the future King James II, was the RAC’s governor and largest shareholder.

It is estimated that the Royal African Company shipped more African people to the Americas than did any other entity during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. England banned the slave trade in 1807 and slavery in 1833.

“At the time,” Newman says, “when I was trying to get funding for my book on the monarchy’s historical links to slavery, some scholars didn’t think it mattered. They were like, ‘It’s state involvement that mattered, not the role of the crown or members of the royal family.’ Because the constitutional role of the monarchy has shifted over time, many people see the British monarch now as just a figurehead, but they weren’t always so powerless. Monarchs were incredibly influential.”

Newman has liked the “idea” of England since before her brain remembered time — the style, the tea, the understatement and the affectations, the Jane Austen. As the Houston native got older, though, her lifelong Anglophilia matured.

In college, she started looking at what the British Empire had done to the world. That led her to study race in 17th- and 18th-century Jamaica, then a major British colony, and based on that research, she wrote “A Dark Inheritance: Blood, Race and Sex in Colonial Jamaica” (Yale University Press, 2018).

Currently, Newman’s writing “The Queen’s Silence: The Hidden History of the British Monarchy and Slavery,” which will be published by Mariner Books in 2025. It features the rest of the research that got Charles III to speak up.

“The monarchy is about appearing timeless, and the only way that they change is if there’s overwhelming societal pressure,” Newman says. “Their whole shtick is, ‘We’re timeless. We represent continuity, and everything else around us is chaos, but we’re the pillar of continuity and national identity and pride.’

“[Corporations are] never going to be at the vanguard of anything, and neither is the monarchy. The monarchy has a team of people who do polling, just like a political party, and they assess ‘How do you feel about X?’ So Charles knows that a huge percentage of the public is not supportive of him apologizing for slavery — but then another section is. And then there’s also a sense where he has to decide: What does he think the right thing to do is? And what does he want his legacy to be?

“He’s not going to be monarch for very long.” Charles is 75. “Let’s say he dies in 10 years. He will have only been monarch for 11 years or so, and if he’s just there as this transitional figure and he’s got nothing that historians can look back and say, ‘This is what Charles did,’ I think that’s going to weigh on him. I think that’s why he’s hoping, potentially, to address this.”