.png)

Health & Medicine

A spoonful of history helps the willow bark go down

An annotated tour of artifacts and curiosities at the School of Pharmacy Heritage Trail

Since 2021, visitors to VCU’s Robert Blackwell Smith Building have been greeted by a museum-like array of display cases, timelines, artifacts and documents from the 19th and 20th centuries. They’re part of the School of Pharmacy Heritage Trail and help unspool the history of the profession in Virginia and VCU’s place in it.

With help from university archivist Jodi Koste (one of the trail’s advisers) and donor and pharmacy school alum Al Schalow’s (B.S.’61) narration of the project’s online video series, we took an annotated journey through the Heritage Trail’s primary display case: an exhibit of objects, records and everyday tools and medicines that help explain pharmacy’s history — from the illustrious and charming to the curious and sometimes infamous.

Green power

Plants ruled in the generations before modern chemistry, and some present-day medicines and supplements can trace their beginnings to something in the ground. For example, “various concoctions were made from willow bark,” Schalow says, and people chewed its twigs to relieve pain. The plant’s active ingredient, salicin, was isolated in 1820 and led to the synthesis of aspirin. The Ephedra sinica plant, meanwhile, helped scientists create medicines to treat asthma, allergies and nasal congestion, including those red pseudoephedrine pills helping you conquer your latest head cold.

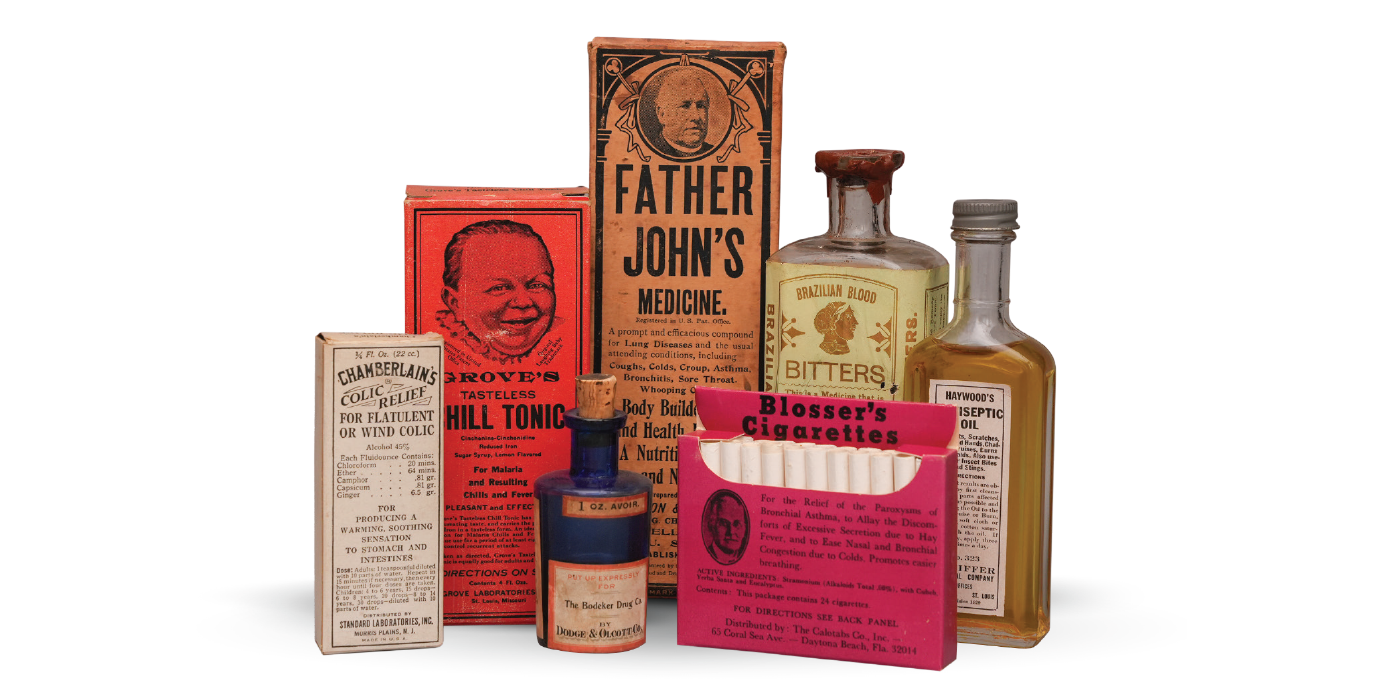

The frauds and their potions

The second half of the 19th century was the wild era of American pharmacy and medicine, and many now-notorious “patent medicines” of the time weren’t U.S. Patent Office-approved; they were simply proprietary. Often called tonics or elixirs, they were of questionable effectiveness (and wildly profitable, thanks to bogus and largely unregulated advertising). Some included toxic or addictive ingredients like cocaine, morphine or opium. “In many areas of the country, medical help was scarce or unavailable [and] charlatans took advantage of people,” Schalow says. The 1906 passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act (part of a wave of early 20th-century progressive reforms) finally forced manufacturers to put a list of ingredients on products and allowed for legal action against misleading advertising, ending the worst of the quackery.

Pharmacy’s stethoscope

The tools that foretell modern pharmacy: pill rollers to form and cut pills, cork squeezers to size stoppers for bottles, and the mortar and pestle to grind and combine powdered medicines (also to make a mean mojito). The most ubiquitous of pharmacy symbols — “just like the stethoscope became a symbol of medicine,” Koste says — mortars and pestles are still sometimes used today in pharmacies that do a lot of compounding by hand. VCU has more than 300 in display cases throughout the Smith Building, including on the fifth floor outside the pharmacy school’s compounding laboratory.

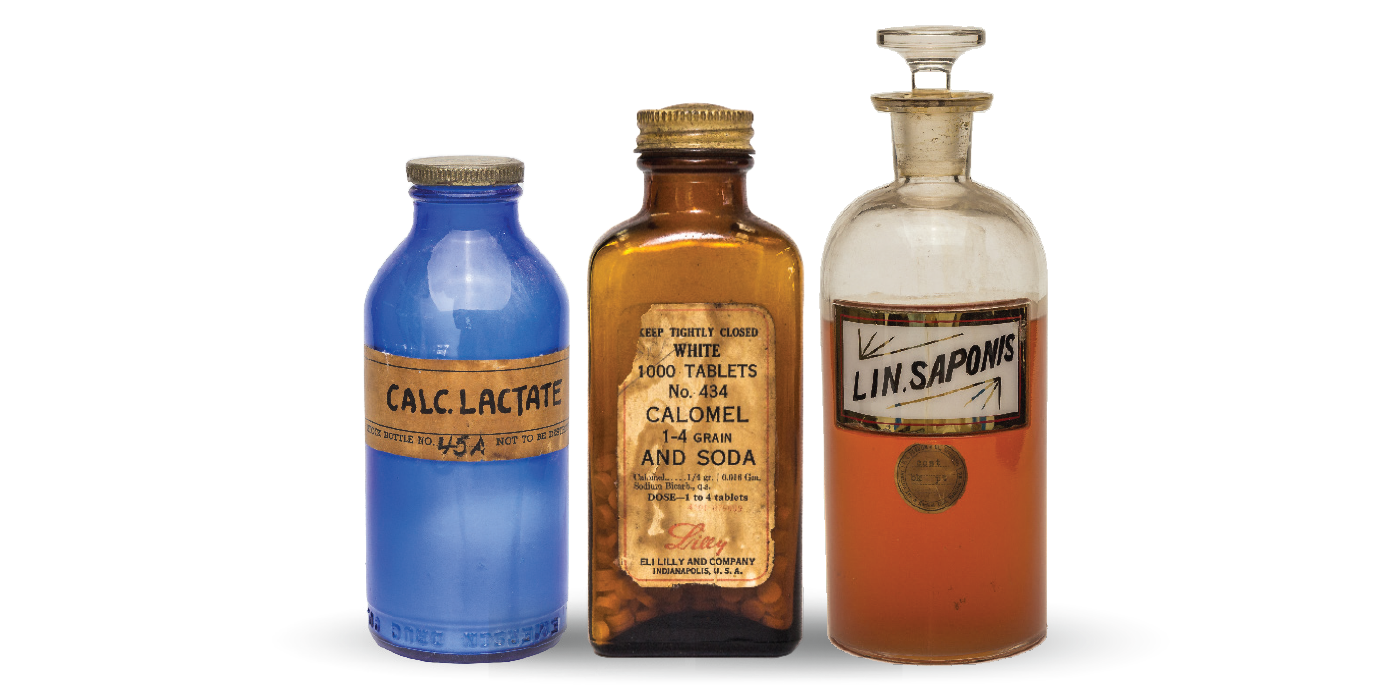

Apothecary bottles: Made for substance — and style

These bottles, especially the blue ones, are among the first items you notice when you enter the Smith Building lobby. Their colors and designs are mostly for function: Amber or blue bottles were for light-sensitive medicines (amber is still used today in plastic medicine bottles and beer bottles), and pharmacists used textured and/or green bottles to label poisonous products. Pharmacists in the late 1800s and early 1900s sometimes added a little flourish to their bottle-labeling by using “label under glass” bottles. The eponymous feature was written in Latin and embossed with gold foil.

‘Think of it as their filing cabinet’

Avert your eyes, spreadsheet buffs. This is not an ancient tome. It’s a stack of prescription files from an Appomattox, Virginia, druggist, circa 1920. And this is how late 19th- and early 20th-century pharmacists organized what they filled and sold to patients. While you give your left brain a moment to recover, here’s Koste again: “Whenever a physician wrote a prescription, they would give [the patient] a piece of paper, and the patient would go to the pharmacy. When the pharmacist filled it, his filing system was to smash it on that wire, and he would keep going until the wire filled up. And then some of them would hang in the ceiling of the pharmacy because they kept them for a while in case they needed to refer back to them. Think of it as their filing cabinet. It’s my favorite piece from the display. It almost looks like a wasp nest. We have a few old prescriptions [in the university archives], and they have a center hole in them, so we know they spent part of their life on the old stick.”

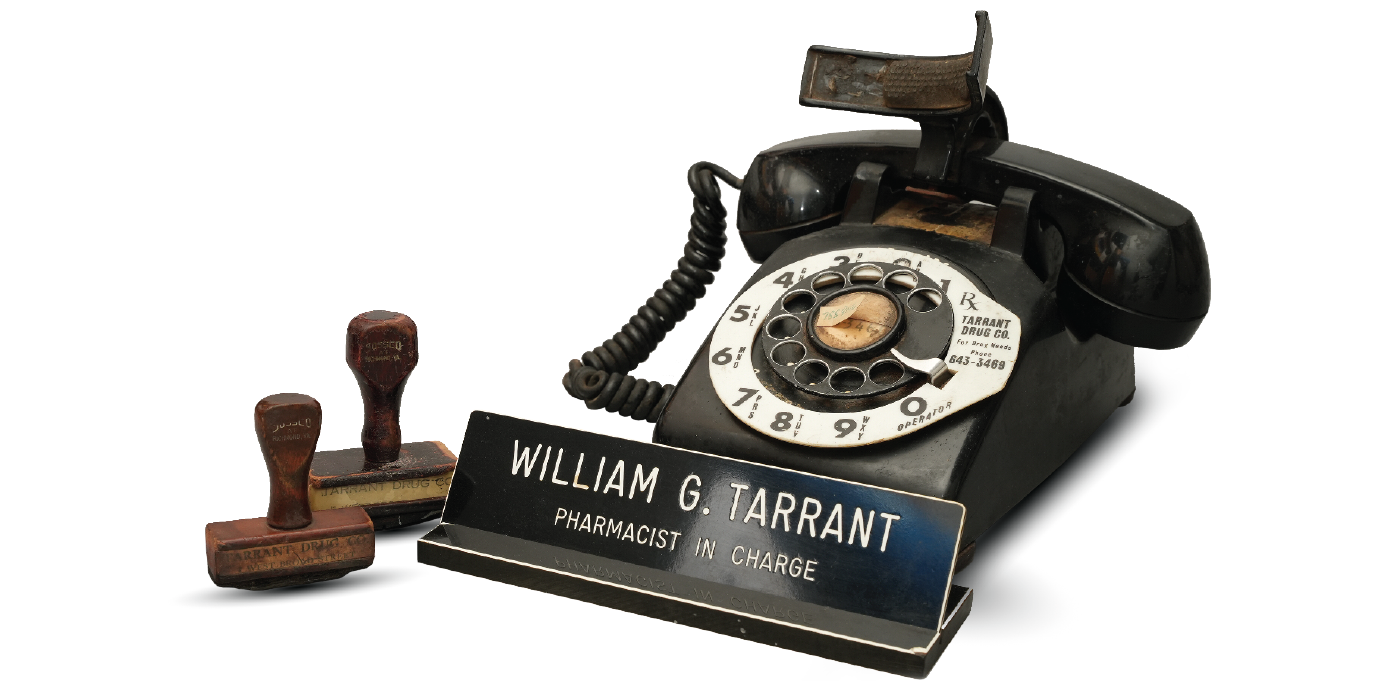

History down the street

Today, with CVS and Walgreens owning huge swaths of the prescription drug market, it’s easy not to realize that for most of the past two centuries, running a pharmacy meant running a small business. One of Richmond’s more famous pharmacies was Tarrant’s in Monroe Ward. Opened by William G. Tarrant in 1905 and operated by Tarrant and later his son, William G. Tarrant Jr. (B.S.’32), the drugstore occupied the ground floor of 1 W. Broad St. for more than 80 years. Its yellow “Tarrant Drug Co.” decals are still on the windows, historical nods from Tarrant’s Cafe, the 150-year-old building’s occupant since 2006.