Arts & Culture

Hot Cocoa

Farah “Cocoa” Brown (B.S.’95) spent a decade learning to be a stand-up comic, but it took real life to teach her how to be funny. Here, the alumna and veteran entertainer — she’s worked with Tyler Perry and has recurring roles on Fox’s “9-1-1” and Netflix’s “Never Have I Ever” — talks about the state of stand-up, her comedic voice and how she embraced Farah to find Cocoa.

If you’re at all transcendentally predisposed, or if you’ve just had a certain amount to drink in this particular comedy club, you can probably see Cocoa Brown’s comic nimbus.

Right now, Brown is absolutely inhabiting the stage, holding forth with charm and dominance at the Comedy Loft, a Washington, D.C., venue that sits under an older hotel an easy walk from the Dupont Circle fountain. Brown (B.S.’95) is partway through the first of two hourlong sets this January night and rollin’ like warm butter on Thanksgiving.

“Is my eyelashes coming off?” she says to the crowd. They say/ shout “Yes!” like they know her, and Brown, as if it were part of the show, just pulls off the lashes, sprinkles them on the stage and continues with a bit that ends with an invocation of Queen Latifah. It’s very funny. We know this because not only is the crowd laughing in a way that makes you think the club’s one bathroom isn’t enough, but also because the guy in the leather jacket and gold chain a table over just said so devotedly, loudly and with such emphasis, he could be speaking in italics. He can see her nimbus, too.

Farah “Cocoa” Brown, who studied mass communications at VCU and now lives in Atlanta after growing up in Newport News, Virginia, has been a stand-up comic for more than 20 years, releasing two comedy albums, 2015’s “One Funny Momma” and 2022’s “Famous Enough.” But, she says, she only really figured it out in the past eight or nine. In between all this growing and honing her act, Brown cultivated a well-rounded showbiz career, notably starring in Tyler Perry’s “The Single Moms Club” and “For Better or Worse,” Ryan Murphy’s “9-1-1” and Mindy Kaling’s “Never Have I Ever.” In total, she has more than 100 film and TV credits.

But as is clear in this dark, wood-paneled club, stand-up is where her heart glows — where she transforms most fully from Farah to Cocoa. Here, Brown ruminates on the art of comedy, the current era of stand-up and how she found her style through herself.

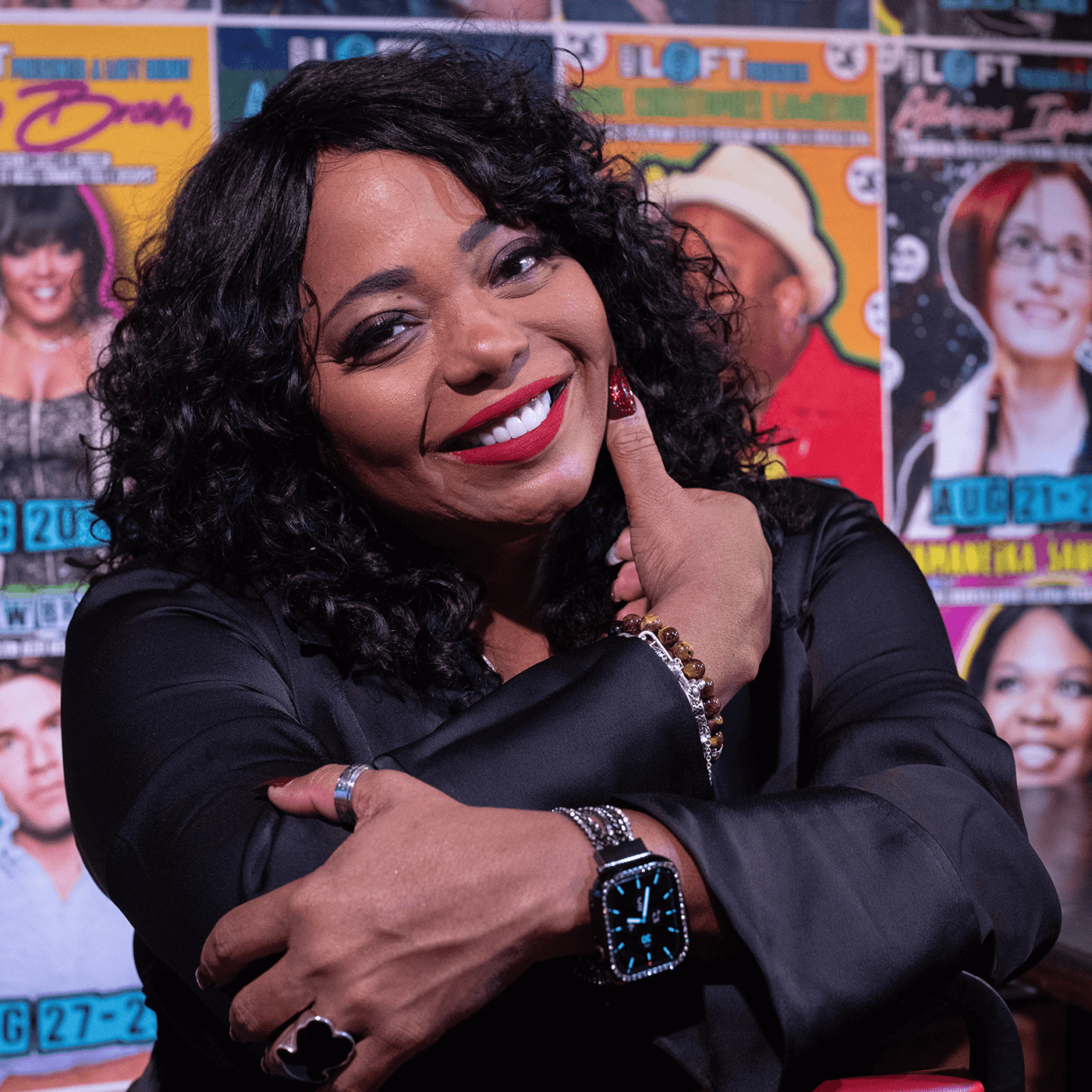

Cocoa Brown enjoys a lighter moment before a show.

I DID A SHOW in north Dallas a few months before my divorce was final. It was late 2013, early 2014, and I was doing an hour headliner set at the Addison Improv. At the time, a lot of my material, typically about being married or trying every fad diet to lose the baby weight, had more and more to do with the divorce.

When I came off the stage after that set, which, in my mind, went well, my opening comedian came up to me and said, “I’m gonna need you to go somewhere and heal.” I asked him what he was talking about and he said, “You were so angry. Man, like, you scared people into laughing.”

This is a joke I told back then:

When you’re so fed up with your husband you grab a glass of wine and unplug his sleep apnea machine in the middle of the night and sit back waiting to see what happens.

He had a point.

It took some thought and reflection, but after a little while it dawned on me that I was dealing with all my hurt, my pain, my disappointment and my feelings about my marriage failing through my jokes.

When I started stand-up, my mentor, the late and legendary godfather of D.C. comedy Darcel “Fat Doctor” Blagmon, told me that great comedians mastered the art of taking their pain to the stage and using it to make an audience laugh. When we first started working together in 1997, Doc — who mentored Roseanne Barr, Andrew “Dice” Clay, Sam Kinison, Martin Lawrence, among others — told me a real comedian does not find their real voice till about year No. 9, year No. 10.

I thought he was nuts. It don’t take that damn long to find your voice. I know who I am! As God as my witness, year No. 10 is when that happened. It was me venting all those emotions from my marriage ending and realizing I’m about to be everything I said I never wanted to be. I’m going to be a single mother — a baby mama. It went from me talking about other people’s mess to me talking about my own mess, and I realized I’d made it to another level of creativity. My pain became the setup and how I overcame it became the punchline.

I look back on that time and I thank God I had stand-up comedy to do that because I probably would have spent a trillion dollars in therapy. I had to feel so many emotions and feel my reactions to them, all so I could find myself on stage and find myself in life. I was able to go up there every weekend and purge my everlasting soul, and I think during that time is when I realized that you don’t have to be anybody but your damn self on this stage.

Brown performs stand-up during the first of two hourlong sets from a show in Washington, D.C.

When I first got in the business, I had a “pick me” mentality. Let me have the best joke. Let me have the best set and, hopefully, somebody in this audience will pick me or will take me and make my career just blow up, jump-start. My material was a melting pot of what I thought the audience wanted.

I’m now in the position where I feel like I’ve already been picked. I work. I do films. I do television. I do stand-up. I write. I produce. When I go on stage, yes, I want to make you laugh. That’s my goal. But I’m going to get some stuff off my chest, too, and it took that period of me using that stage as my therapy to figure out that balance, that comedic recipe. Before that, even if I wasn’t totally aware of it, I was still learning just how to be on stage — and it had nothing to do with being funny.

There are so many things you have to think about before you get to “funny” when you’re a stand-up comedian. You’ve got to have rhythm, cadence, inflection, presence. You’ve got to think about where you stand on the stage, how you stand, what your face does, what your hands do, what your body does, even where you look and how you look there. Art is not spontaneous. Art is practice and work. It’s style and soul, and if you do all that and you have enough talent, it’ll look spontaneous. The Fat Doctor taught me that.

I met him after my third time on stage. I was performing at the now-long-gone Comedy Spot in New Carrollton, Maryland, just east of D.C., doing my best to escape the boredom I felt working in corporate America. I was working as an advertising account executive at Ringling Bros., and when I started bombing that night — I was only getting stares — I panicked and started talking about how I literally worked for the circus. At the time, I really thought I knew what I was doing on stage. I’d been performing my whole life — in plays, in musicals, for my parents and just about anyone who would pay attention, but I learned that night that the audience knows when you’re faking it.

When I started talking about my circus job out of desperation, the audience warmed to me because I wasn’t lying to them or myself.

After that set is when Doc, who died in 2020 in his mid-60s (or so we think; Doc never revealed his age), approached me. He told me that I had great stage presence, but I needed to learn how to structure my set and learn how to write a joke. I had great ideas, but I didn’t know how to put them out there, yet. And Doc told me that even though I was green, that night I learned something it takes a lot of comics years to learn: Real is funny.

“When I first got in the business, I had a ‘pick me’ mentality,” Brown says. “Let me have the best joke. Let me have the best set and, hopefully, somebody in this audience will pick me or will take me and make my career just blow up, jump-start. My material was a melting pot of what I thought the audience wanted.”

I still have my notes from my first session with Doc. They’re in a black-and-white, old-school composition notebook. It’s got all the early jokes and bits that Doc helped me turn into material. It’s also got what I learned about the ABCs of stand-up. He told me what a bait-and-switch was, what a callback was, and he also told me about booking my own gigs, what should go on the tape you send to promoters and club-bookers, and what to charge based on your experience and film and TV credits. He broke down everything about stand-up from the art of it to the business, and maybe most importantly, he gave me an equation that I still use to this day whenever I write a joke: Simplification times exaggeration equals funny.

Doc always said joke-writing isn’t brain science, but it takes a certain skill. You need to know how to make the setup simple enough for the dumbest person in the room, give it a little flavor with something that conveys “it sounds crazy, but …” and deliver the punchline using every part of you — verbal, physical and spiritual.

One of my first signature jokes is about being a plus-size woman trying to buy lingerie at Victoria’s Secret. I wrote it in 1998. It’s really simple but it still gets a big laugh. It goes like this:

Us bigger women like to get sexy, too, but where can we go to get lingerie (which I purposely mispronounced “ling-ger-ee”)? It sure ain’t Victoria’s Secret, because I know what the secret is … ain’t nothin’ in there can fit me!

You can see Doc’s joke equation in it. There’s a simple setup (bigger women like to get sexy, too) and then the exaggeration (nothing in there fits me). Doc stressed structure and smart writing. He stressed the fundamentals. When you look at the cats that came up in the 1980s and the ’90s, maybe even the 2000s, we were probably the last generation that was meticulous about structure, and I may just be old and cranky and yelling about kids on my nice Atlanta lawn, but it seems like structure is a dying art — or at least an underappreciated one.

This is nothing against the new comics because they’re making their way and making their voice heard, too. But back in the day, you couldn’t just call yourself a comedian.

Today, if you do a funny skit, get 500,000 likes on social media, you can call yourself a comedian and get work in comedy clubs overnight, thanks to your follower-count and self-promotion. (Bookers and club owners, not surprisingly, like acts with established fans.) We didn’t have social media when I started. Hell, if you just had a cellphone, you were making money.

A lot of the younger comics coming up, their jokes aren’t as structured. Those comics can be funny, but they’re all over the place because they were never taught the game. They didn’t have a Fat Doctor. They’ve never had to touch a stage and learn how to read and hold a room, how to scramble if your material’s not working — and I doubt any of them ever worked at the circus.

Twenty-five years ago, you had to be a good writer. You couldn’t be on stage faking it. The audience didn’t play with the funny. They would know if you were up there not knowing what the hell you were doing. Audiences demanded to be entertained. They didn’t care who you were, how many TV shows or movies you had done. If you weren’t funny, if you didn’t make them laugh, you were getting booed off the stage.

I understand comedians’ frustration with the state of stand-up because I’m frustrated with it, too. I respect the hustle of some of these newer comics who have the gumption to flip the game in their favor. They take it seriously, do their act in a way that works for them and on stage, but I’ve seen a lot more who think they can turn one 10-minute YouTube skit into a set, while we work tirelessly on our craft and then watch someone who doesn’t have any material or training skip over us.

I started during “Def Comedy Jam,” the landmark 1990s HBO stand-up comedy series that launched the careers of Lawrence, Dave Chappelle, Bernie Mac, Steve Harvey, Sheryl Underwood, JB Smoove, Cedric the Entertainer, D.L. Hughley, Chris Tucker.

“Def Comedy Jam” was the thermometer. It was the judge and jury. If you made it there, you were set for life. There are people who killed it on Def Jam in the ’90s who are still working and getting top dollar because the audience that follows them understands that they’re going to see a true, well-structured comedic set.

This new generation, they don’t always know what that looks like. Being able to write a funny tweet or make a funny YouTube or TikTok video is a talent, but it’s not the same talent as being able to own a room for five, 10, 20 minutes or an hour. Five minutes is a really, really long time when nobody laughs. I know. That’s why I had to talk about the !@#$%^& circus.

Brown, center, has more than 100 film and TV credits, including a starring role in the 2014 movie “The Single Mom's Club,” directed by Tyler Perry. (Courtesy of Cocoa Brown)

Some of it’s a generational divide, too. Social media comics may not take the structure and skill of writing and delivering a joke so seriously because they don’t have to.

In the past, the material changed stand-up. The format and execution stayed the same. Comedians pushed at taboos, crossed lines. Urban comedy is an example. Once deemed too blue for mainstream, it’s now crossing over and basically controlling mainstream. Today the venue’s changing, too, moving from the stage to the internet, and that’s messing with comedy’s fundamentals and, more generally, tastes and norms.

There was a time when comedy was truly the definition of freedom of speech. The 1970s through the 1990s is considered a stand-up golden age, thanks to the proliferation of clubs as well as the creation of cable television, which offered a level of exposure clubs and albums couldn’t — and society didn’t seem so hell bent on being politically correct. People came to see comedians say what they were thinking, and it was welcomed and appreciated. But now so many groups want to take everything to task and be offended by everything, even when it doesn’t concern them, and stand-up has sort of become like playing Russian roulette on stage. People are more sensitive, and they don’t just get offended and move on. They now have to create this whole platform of You offended me. I want everyone to know you offended me. I want everyone to be offended with me, and I want them to hate you and cancel you, too. It’s kind of made comedy not as free and not as fun.

I find myself asking people their opinion of a joke I write before I tell it, just to be safe. I’ve also chosen to avoid certain subjects because of that. When I first got into comedy, it was so freeing to me. Coming from a traditional Southern household, I just didn’t say certain things out loud. Stand-up allowed me to let it all out and express myself in ways that maybe I wouldn’t have done if I wasn’t a comedian — cursing, talking openly about sex and sexuality, social issues, politics, etc.

Now, could a comedian push the button and overstep? Yeah. But there are some comedians — that’s their schtick. Their whole job when they step on stage is to push buttons. George Carlin, right now, would probably be canceled because he spoke so much truth.

It just kind of sucks because it seems like there’s so much negativity and bad going on. Let humor and comedy be what it is. Stop looking for a reason to be offended. Let it go. Instead, they’re looking for something to pick apart.

“The minute I figured out how to go full transparency is the minute I stopped hearing comparisons,” Brown says. “That is when I realized I had truly found my voice.”

It doesn’t affect me as much as other comics, though, because there are topics I will not touch on. I’m not a big political comedian because I don’t want to divide the room. I want my laughter to be collective. I might say something here and there, which I know is just going to get a laugh and it’s not really going to have people squirming in their seats. I don’t really talk about religion too much. Once again, it’s a room-divider.

My style is your favorite friend keeping it real with you in a conversational way. I also read my rooms and I edit jokes to fit. Fat Doctor taught me to write your jokes clean, then you can “season” them up for more mature audiences or outlets, but nobody’s out there trying to offend you, honey. Last time I checked, the average stand-up is not going on stage to piss people off. They’re going on stage to make you laugh and to make you think.

I never understood people who come into a comedy club pissed off and with no desire to laugh. Why are you here? It makes it even harder for someone to find their voice on stage when no one’s operating in good faith. Authenticity is the most important thing, from the crowd and from the comic, and when I realized that is when my act took off.

It went from people going, “Oh I like her, she’s funny” to “Oh my God, I want to hang with her,” hitting me up on my inbox like we’re homies, asking for advice about their marriage. I went from being Cocoa Brown to Cocoa Oprah.

It garnered a different kind of respect from my audience and from my peers, because one of the biggest things I noticed is that for maybe the first 10 years of my career, I was always compared to other people. “Oh, you remind me of Mo’Nique. Oh, you remind me of Sommore. Oh, you remind me of Adele Givens.” In the beginning, I was flattered, as these ladies are legendary, but then it bothered me because I wanted to be me. I wanted to be seen as Cocoa Brown.

The minute I figured out how to go full transparency is the minute I stopped hearing comparisons and heard, “Yo, I saw this comic the other day and she was like a baby Cocoa Brown.” That is when I realized I had truly found my voice — and Fat Doctor told me that. It took me going through what I went through for me to stop getting the comparisons.

Thanks to comedy, I have healed from a lot of traumatic experiences: my divorce, the deaths of my parents in 2021 and 2022, becoming a Type 2 diabetic while carrying my son. I’ve been fortunate that my audiences love me enough to take this ride with me. But I have built a fan base that comes to see me, and they know not only are they going to laugh, they’re going to feel and they’re going to think.

For me when I first started stand-up, the energy was Who are you? You better make me laugh. Now for me the energy is Oh my God, it’s her! Oh and she’s funny, too! Or I have so many people come to me and say they didn’t know I was a stand-up comic because they only know me from “9-1-1” or Tyler Perry. They have no idea that I was a stand-up comic for many, many years before I ever got my first TV or movie role.

Now I know that people who come to see Cocoa Brown are coming to see authentic, true stand-up comedy. I’m not up there with that pick-me, Donkey-from-“Shrek” mentality. Whether I get a standing ovation or not, I walk off stage knowing I was authentically and genuinely, completely myself and I gave them Farah and Cocoa. I gave them ME.