Arts & Culture

The Delight Is in the Details

David Ashton (B.F.A.’62) founded two creative agencies, rescued a 19th-century farmhouse from ruin and helped make baseball parks timeless again. Here, he explains why simple is beautiful (though never easy) and the importance of trusting your first idea.

“I don’t want this article to be just about Camden Yards,” David Ashton (B.F.A.’62) politely requests as we sip tea in the lobby of the Quirk Hotel in Richmond. He and I — and Ashton’s daughter, Paris Ashton (B.F.A.’85) — are occupying a trio of upholstered chairs and couches in a front corner of Quirk’s spacious foyer on a drab January Wednesday.

For the past 90 minutes, Ashton and I have been chatting about his nearly six-decade career in graphic design, his philosophy as an artist and the painstakingly and lovingly restored 19th-century southern Pennsylvania farmhouse he shares with his wife, botanical artist Meg Page. And yes, his work on Oriole Park at Camden Yards, the Baltimore Orioles baseball park that revolutionized American stadium construction and whose details Ashton designed in a six-month sprint just before it opened in April 1992.

Now the interview is returning to that topic, and Ashton cautions me: We can talk about Camden Yards, but he doesn’t want it to swallow the story. The ballpark has been written about before. It’s a gentle reminder.

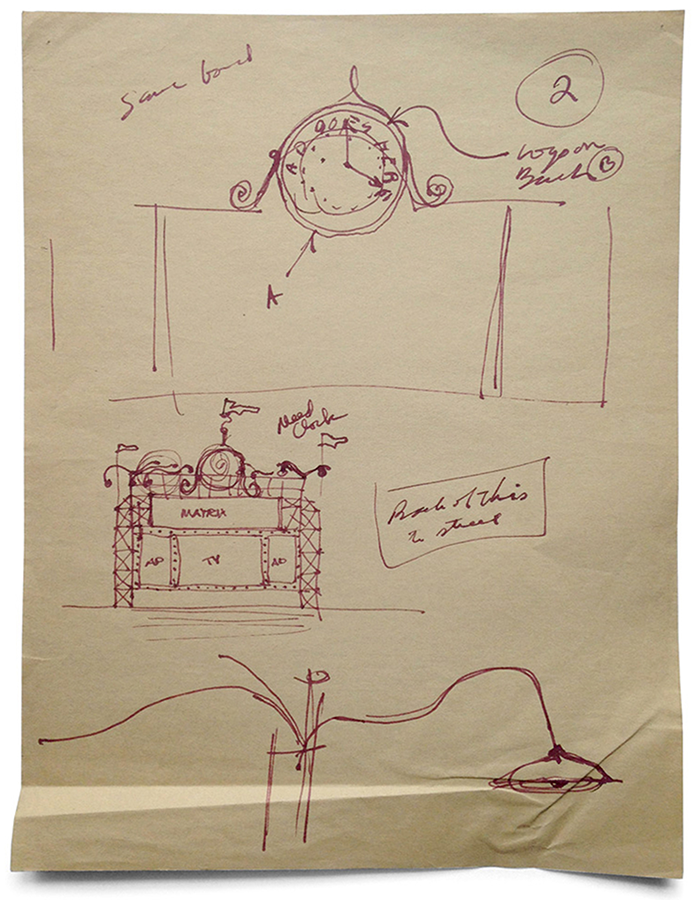

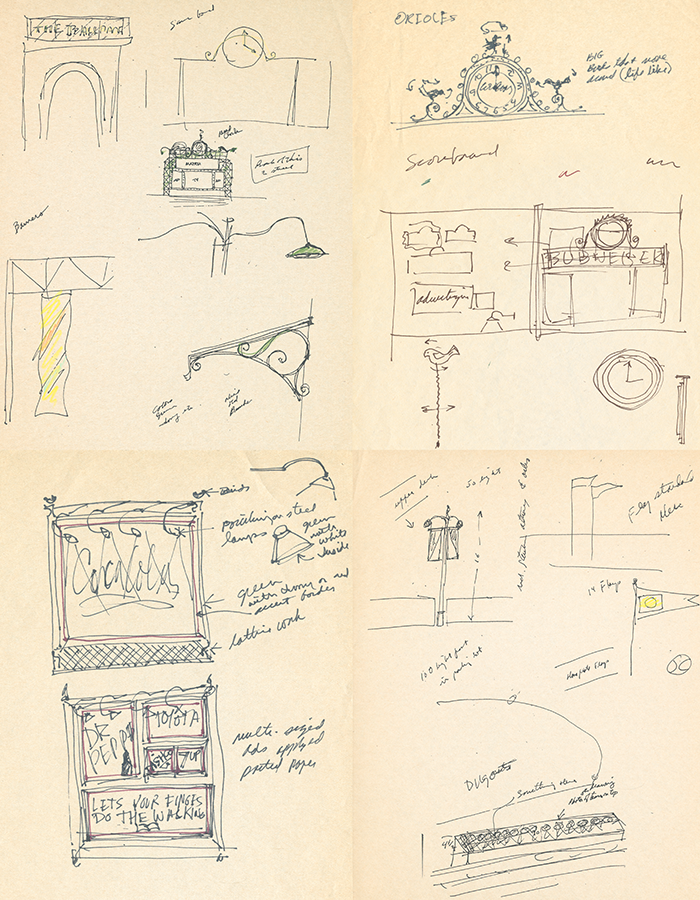

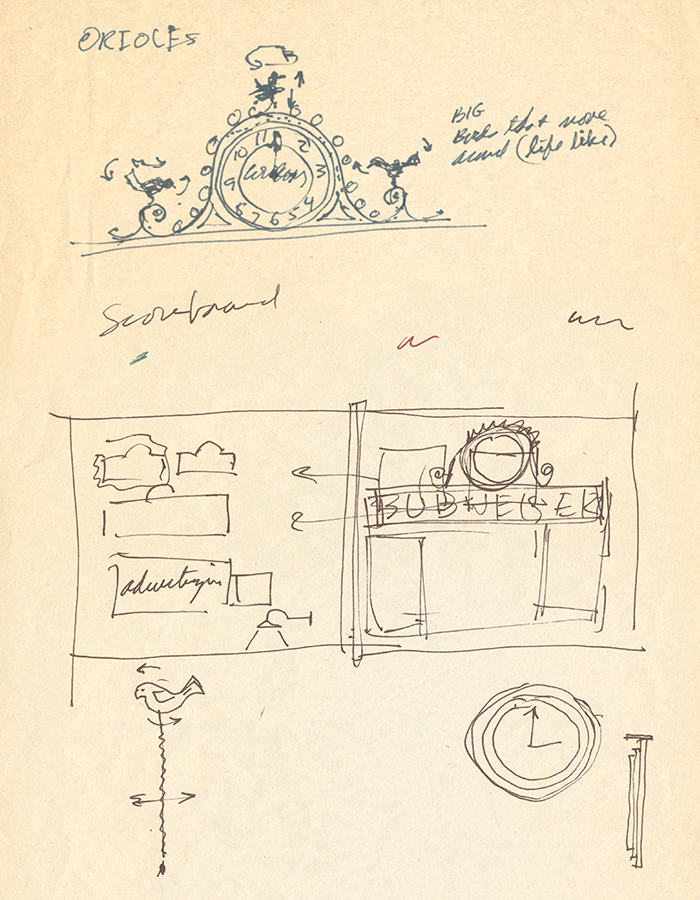

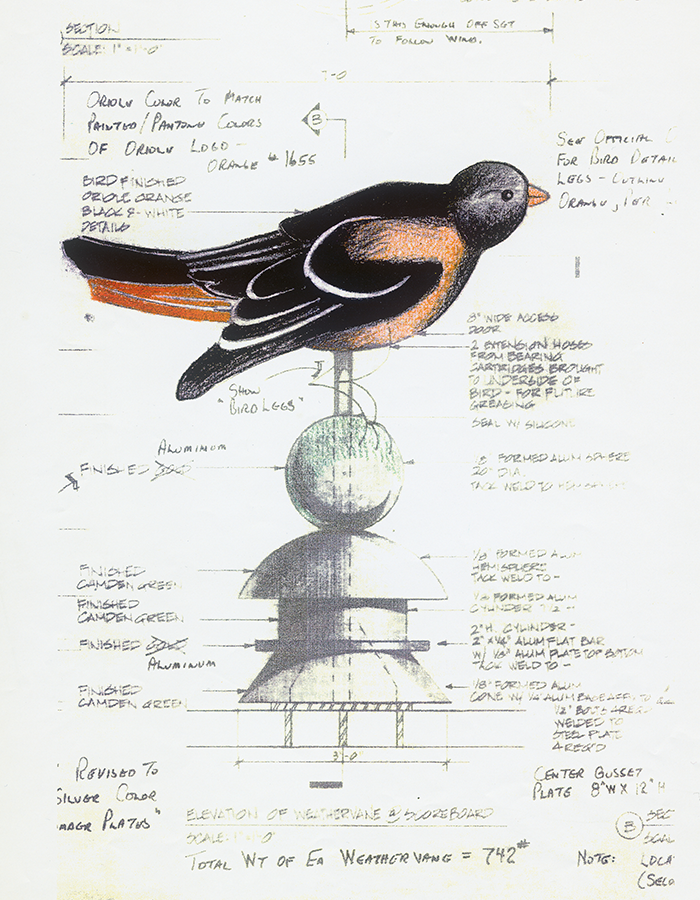

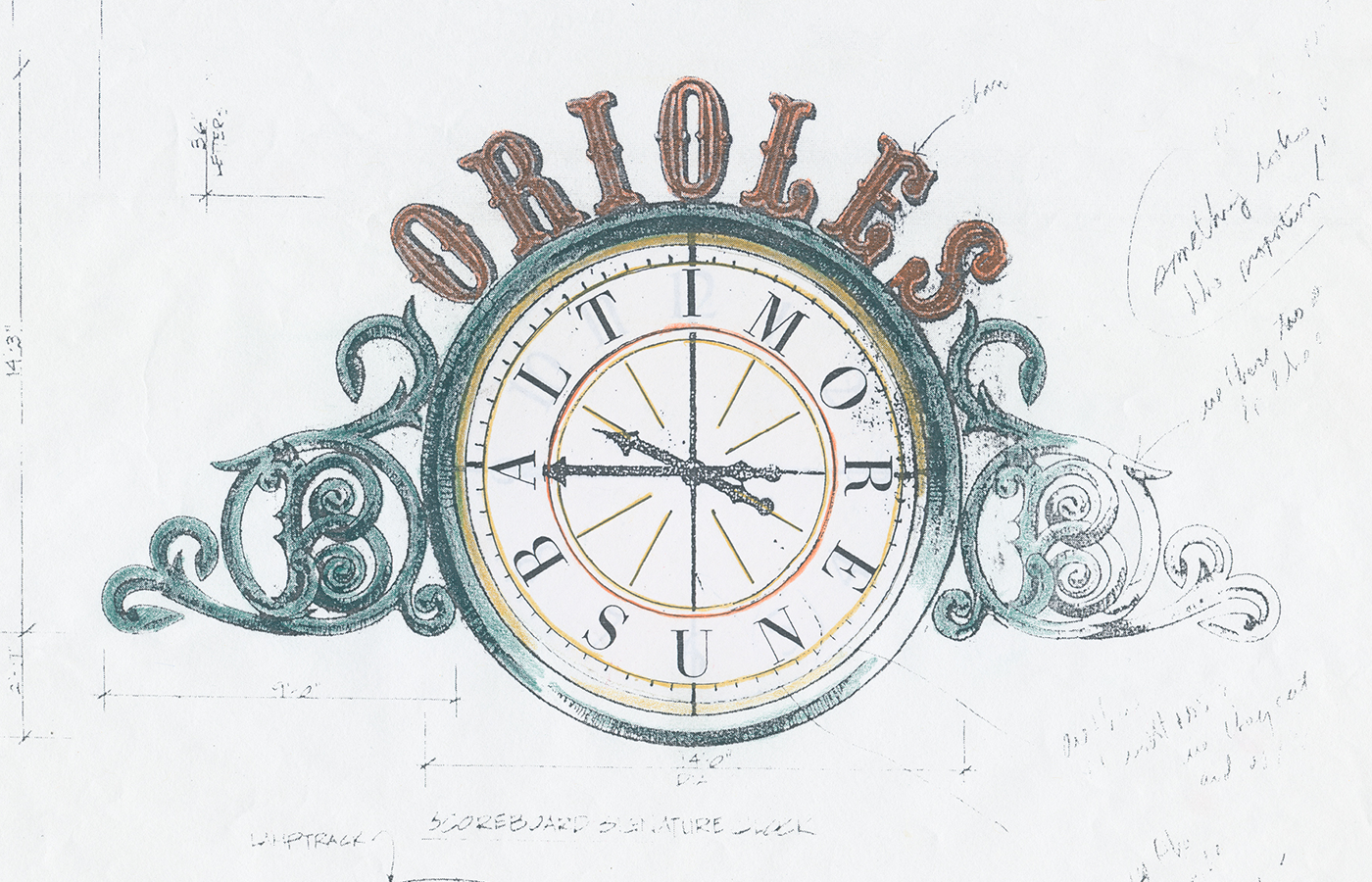

But before we move on, some context for the non-sports crowd: Made of brick and steel and built blocks from Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, Camden Yards emulated baseball’s quaint early-1900s jewel box ballparks, rejecting (and almost overnight making obsolete) the multisport concrete bowls that dominated stadium construction in the second half of the 20th century. It also was the largest project of David Ashton’s career, an example of his love of detail and old-time aesthetics, and a validation of his instincts. Many iconic characteristics in Camden Yards — from a set of oriole-shaped weathervanes to an antique-style scoreboard clock — were brought to life from drawings Ashton sketched with a Montblanc pen while on his first tour of the unfinished ballpark the autumn before it opened.

That’s the Cliffs Notes on Camden Yards. And though there will be more, it’s a supporting actor in this film. The protagonist is David Ashton.

Raised in a Quaker family, Ashton grew up in small towns in northeast Maryland. His mother, Betty, was a stay-at-home parent. His father, Bob, managed a hardware store and lumberyard and was, not incidentally, a master craftsman. “He could chop out a doorway with a hatchet and it looked like he had done it with a handsaw,” Ashton says. Betty and Bob Ashton’s oldest of three children created things from a young age, sewing clothes for his toys, assembling scrapbooks, building car engines and sketching graphics for school plays. After attending Richmond Professional Institute (a VCU precursor), Ashton settled in Baltimore, beginning a 58-year career, the last 35 as head of Ashton Design, now the city’s oldest design agency.

At 33, Ashton was featured in Communication Arts magazine, his field’s most prestigious trade journal. He designed the popular “flock of geese” sculpture at Baltimore-Washington International Airport, published books with Dutch photographer Robert de Gast and worked alongside artist Milton Glaser (he of “I ♥ New York” fame). He founded two companies and reinvented himself over and over again in an industry that has morphed from Mad Men-era drafting tables to Adobe Photoshop and TikTok.

His philosophy as an artist has rarely, if ever, wavered: Keep it simple, keep it appropriate, think about how everything fits together, and trust your first idea. Now 83, Ashton today lives on Gentle Farm, on 13 acres outside Shrewsbury, Pennsylvania, where you can usually find him tending to the horses and the chickens. His firm is in the hands of two longtime employees who purchased it in 2020. The Camden Yards sketches? They’re in Cooperstown, New York, donated by Ashton to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Among Ashton’s more visible designs: the 150 steel geese, fabricated by blacksmith Tom Moore, that greet travelers at Baltimore-Washington International Airport.

Stories about Ashton’s role in creating Camden Yards (and his diligent in-period restoration of Gentle Farm) are available to anyone with an internet browser. Other anecdotes are less known. One of Ashton’s favorites is the story of how he got into college. He was working as a gas station attendant in Aberdeen, Maryland, in 1958, about a year after graduating from high school, when his girlfriend, a student at Mary Baldwin College (now Mary Baldwin University), suggested he apply to RPI.

“She said she heard that RPI had a new head of the [art] department and that things were really happening there,” he told me by phone in November. “So I mailed samples of things I had done in high school. And then I started getting things back from RPI: ‘As a freshman here’s the things you should bring. Here’s a date.’

“My parents and I got in our ’57 Chevrolet, drove to Richmond. And I went to the administration desk and they said, ‘Sir, we don’t have any idea who you are.’ They sent me to John Hilton, he’s head of the art department. He was in his office, smoking his pipe, and my parents were with me and they were confused. And [Hilton] said, ‘Oh, I think I have your package right here.’ He hadn’t opened it. So he opened it right there in front of us, and he said, ‘OK, I think you’ll do fine.’ And that’s how I got in.

“They didn’t have any place for me to sleep because all the rooms were gone. They put me in the infirmary. I was fortunate nobody got sick and I had the whole place to myself.

“Can you imagine that happening today? A lot of things don’t happen today that used to happen and turned out kind of cool.”

“How long did you stay there?” I ask two months later as we settle into our floral-patterned hotel chairs.

“A whole semester,” he says. “I used a lot of the beds for my work spaces.”

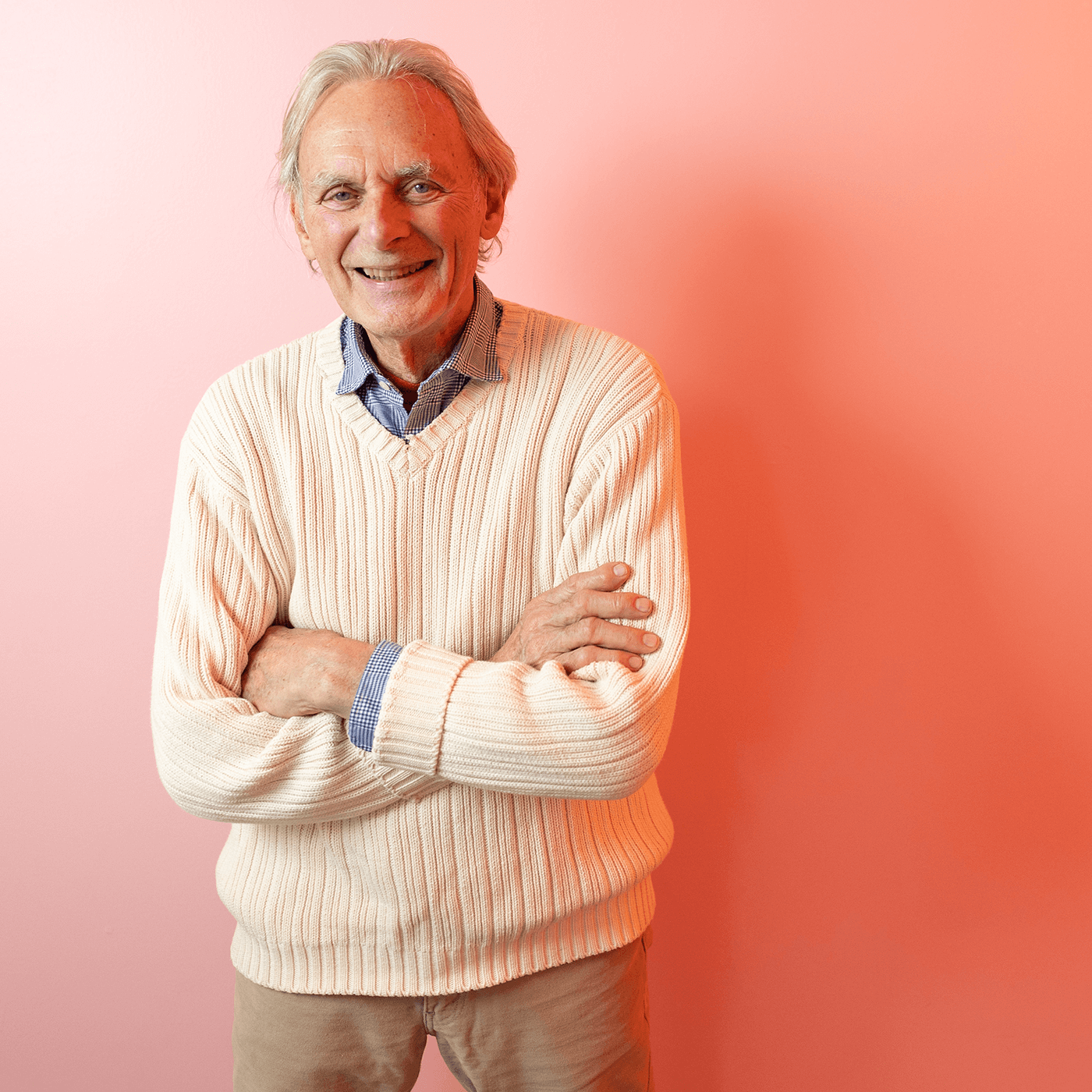

“I’m an artist more than anything,” David Ashton says. “When I was [a child] I was making my own toys. I made clothes for my teddy bear.” (Jud Froelich)

DAVID ASHTON, Paris Ashton and I make small conversation as we warm up in the lobby and peel off outer layers. Ashton is in town visiting Paris, who lives in nearby Henrico County and is director of the Office of Graphic Communications at the Virginia Department of General Services.

Quirk is a 73-room boutique hotel and art gallery on West Broad Street, about four blocks east of VCU’s Monroe Park Campus. It opened in 2015 in the shell of an early 20th-century Renaissance-revival department store, and its lobby is the antithesis of the afternoon weather: bright and cozy — white and light pink walls, a cavernous ceiling with groin vaults and an ornamental iron staircase.

Ashton is handsomely attired in a blue-and-white gingham dress shirt, cream sweater and tan slacks. His to-go cup of Earl Grey is steaming on the side table to his left.

His first company was called Ashton-Worthington. He co-founded it with an account executive named Fred Worthington, whom Ashton met while they were colleagues at Barton Gillette, a Baltimore marketing firm. Ashton started working there in 1962, a few months after graduating from RPI. Six years later, he and Worthington opened their shop.

Ashton was 28, and over the next 17 years, he and Worthington built one of the city’s top design agencies. In 1973, Communication Arts featured the company, and within a few years, the magazine invited Ashton to be a judge at its annual design show in California. He began working with De Gast as well as Glaser, the Push Pin Studios and New York magazine co-founder.

“Milton was a magnificent person,” Ashton says. “You know how some of these guys have huge egos? I worked with Milton on a project for Barnard College. It was an illustration, and I asked him if we could meet in New York with the head of the school. He had a little brownstone. The headmistress was dropped off and she and I walked in together. There was Milton standing in the doorway.

“He said, ‘All these rooms are taken up,’ and he grabbed a few chairs and we met in the hallway. Isn’t that neat? With the president of Barnard, pulling up a chair and we’re sitting right there in the hallway of his office.

“He delivered the illustrations about a month later and [Barnard] wanted some changes. Milton was scheduled to fly out that night to France. He spent all night fixing those illustrations before he went. This is Milton Glaser, the most famous person in our business. I can’t tell you how much that meant to me.”

Ashton-Worthington was a successful company, but by the 1980s, its co-founder found himself feeling stifled. The firm had grown to 25 employees “and all we were thinking about was making money,” Ashton says. “I was running the design department, and Fred was running the business department, and business wanted to do one thing and I wanted to do another.”

Ashton returned to Baltimore from the Communication Arts annual show in 1985 and walked into Worthington’s office.

“I said ‘I’m going to resign today.’ He looks up at me, and I don’t know why he said this, but he says, ‘Damn, I wish I had done it first.’”

“Sounds like it may have been a mutual parting,” I say.

“I don’t know. I found out later from the president of the Maryland Institute College of Art that Fred was so upset that he couldn’t hardly stand it. But I had no clue from him.

“I was upset with the direction of the company. It was starting to lose its edge as a design leader. And I think money is obviously necessary, but I don’t think it should be the only driving force. I left with my assistant. I rented a little carriage house. And a year later I had eight people.”

Six years later, that number was back down to two, after a recession nearly wiped out the firm. “I was going to job interviews,” Ashton says. “No one hired me, thank God, because that’s when I got Camden Yards.”

This is a David Ashton story you can read with a Baltimore Sun subscription. But Ashton delights in telling it.

It was 1991. Ashton previously had created a small brochure for the Orioles promoting their forthcoming ballpark’s luxury suites. Janet Marie Smith, the team’s Mississippi-born architect and one of the first women to hold an executive position in Major League Baseball, invited Ashton to submit a larger proposal to design a main sign, scoreboard graphics, flags, banners and concourse advertising. They toured Camden Yards together. Ashton sketched with his Montblanc, went back to his office and … did nothing.

“The biggest sign I’d ever done was for a real estate company and I think it was 2 feet by 4 feet. What am I going to do for a ballpark?” he says, laughing. “It was overwhelming. And I had no clue how to do it, although I had these sketches. And here they are, laying on my desk.

“And then [Janet] called me after two weeks and said, ‘David, do you want to do this or not?’ And I said, ‘I’ll have a proposal tomorrow morning.’”

“Sometimes we need a nudge,” I say.

“Thank God. She pushed me right to the edge. I took those sketches — and I was pretty much a Xerox wizard — and I hand-colored copies. I made a pocket folder out of dark green paper to mimic the steelwork in the ballpark. I didn’t know what to say [in the proposal], so my secretary and I made up something and stuck it in one pocket. And I stuck a stack of the drawings in the other pocket, closed the thing up and designed an orange band to go around the folder.”

Ashton is moving his hands as though he’s rebuilding the folder in the air.

“I found a copy of their original Orioles logo, which I Xeroxed onto another piece of paper and pasted that on the center of the band. Orange band, green folder. It looked just like it came from the Orioles.

“I was doing this the day I said I’d get it to [Janet]. It was near the end of the day. I rushed down to her office. She wasn’t in.”

Ashton stands and pantomimes slipping an invisible folder onto the light pink coffee table in front of him. He slaps it with his palm.

“I stuck it onto her table and ran.”

He was hired the next day.

PARIS ASHTON leans forward in her chair and motions toward me. Her father and I have been talking about a coffee table book he designed while he was working on Camden Yards.

“Print was always my favorite medium,” he says.

“Why?”

David Ashton says he doesn’t know. But his daughter does.

“Dad creates by touching, feeling, moving, just like he did with those sketches and the Xerox machine: hand-coloring and packaging,” she says. “He made birthday cards for his children every year, handmade, cut out. He’s a tactile artist.”

Paris (she’s a graphic designer, too) inherited this trait. So did her children, Ashton Bressler (B.S.’15) and Holland Bressler (B.S.’21). They’re engineers, tactile creators in their own way, like their grandfather the car engine builder and their great-grandfather the carpenter.

A few minutes later, Paris finishes her thought.

“He also built replica train sets. This is what I grew up watching. He had an attic studio and itty-bitty pieces, like cutting all the shingles for the sides of the houses.”

If you’ve attended a Major League Baseball game in the past few decades at a new (or new-ish) ballpark, you’ve experienced the influences of Camden Yards, Janet Marie Smith and David Ashton: quirky field dimensions, seats closer to the game, open-air concourses, and thousands and thousands of details (murals, banners, signs, artistic nods to hometown cities and past players, etc.) that give each park personality and a sense of place. Some do it better than others, and the details, which can risk appearing twee or gimmicky, are some of the hardest things to get right.

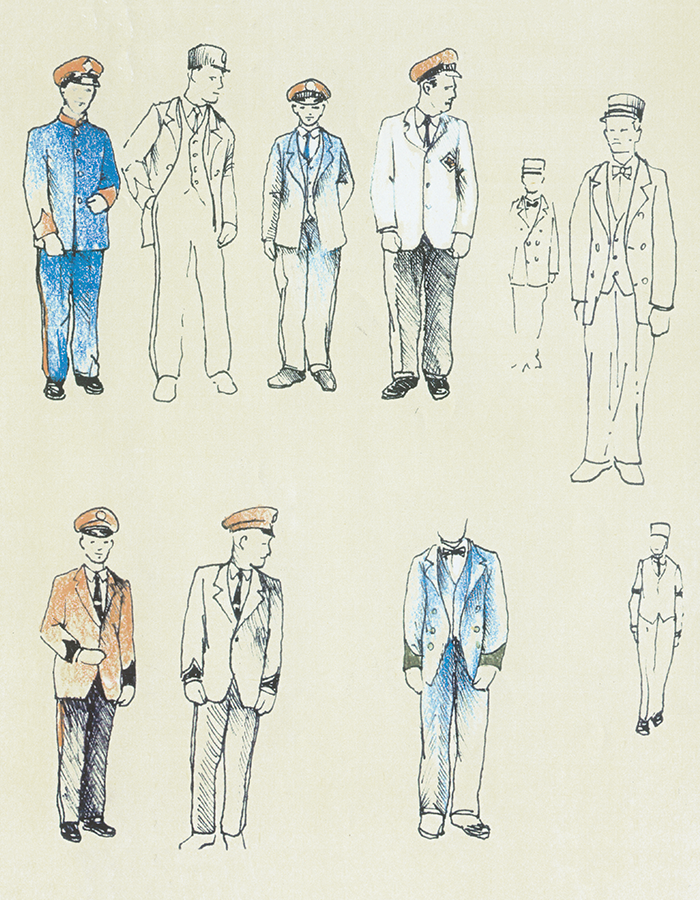

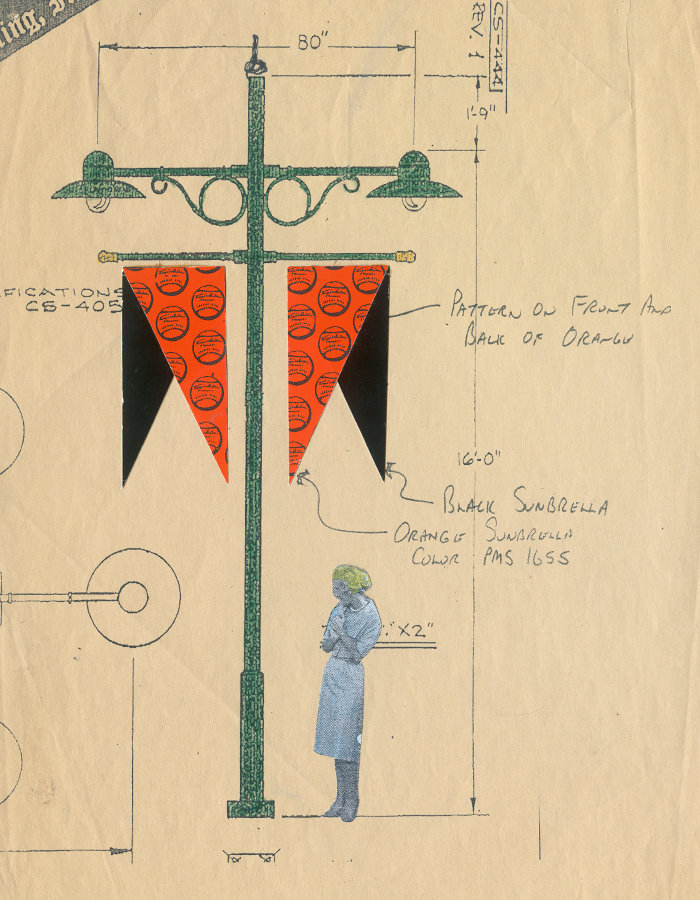

Those details are what Ashton designed in a burst of creativity in the winter of 1992 in Baltimore. He had no idea what to say in his proposal for Camden Yards, but he knew what to put in the ballpark: a vintage hand clock atop the center field scoreboard, a set of oriole weathervanes, a stainless steel “Camden Yards” sign in a classic Caslon typeface, old-time usher uniforms complete with orange bow ties (no clip-ons allowed).

The midcentury stadiums that preceded Camden Yards were reflections of their era: suburban and utilitarian. They were for football and baseball, and with the exception of a few engineering wonders (the Astrodome in Houston, for example), they were dull concrete doughnuts. Ashton’s ideas would be anachronistic there. But inside picturesque, new-but-made-to-look-old Camden Yards, the details fit.

“They were warm,” Ashton says.

“This was strictly baseball, a baseball park, not a stadium. And the other thing was the location: downtown Baltimore. The trend then was to go into the suburbs and build one of these things with all the parking. [Baltimore] had this marvelous 19th-century warehouse [next to where the Orioles were building Camden Yards] that at one point was the longest building in the world. There was an early threat to tear it down. And I was so upset. When I found out they were going to save the warehouse and incorporate it, I thought ‘Yes! They’re going to do it right.’ I’m a preservationist at heart; I preserved an old farmhouse. And saving that warehouse, that made a big difference. It gives juxtaposition. It makes it look like a ballpark should look: like it’s part of the city.”

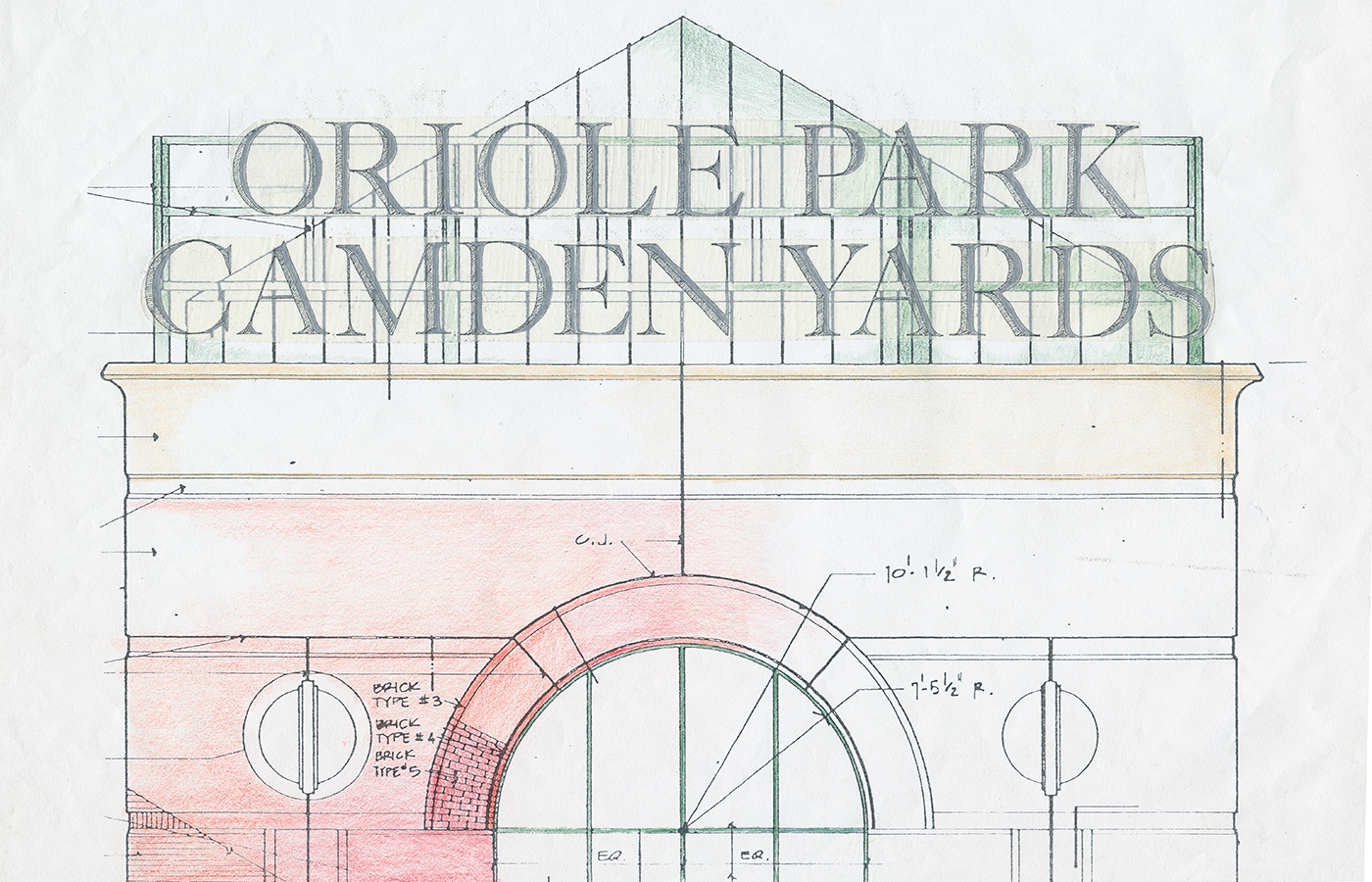

Ashton’s earliest sketches for Camden Yards included an antique scoreboard clock. Subsequent drafts, including the one above, added finer details, including ornate metalwork and 3D letters. All were included in the final design (below).

The vintage hand clock, one of Camden Yards’ most notable features, sits atop the center field scoreboard.

The eight-story brick warehouse is Camden Yards’ signature feature, providing a backdrop to the ballpark and framing Eutaw Street, a 1,000-foot pedestrian concourse behind the right field bleachers. There’s a sense of enclosure. At the northernmost point of the alley are a group of sculptures.

“They wanted to do retired numbers, put them up on the wall, little plaques,” Ashton says. “I said, ‘No, let’s make them’” — Ashton pops up from his chair and raises his hand to eye level — “‘this tall, take the number, make it out of stainless steel, three-dimensional [and] put them on mounts around the concourse.’ I said, ‘People will want to take photographs of themselves.’

“Every time I’ve been to the ballpark, those things are crowded with people taking pictures of themselves and those numbers.

“It was an old-timey ballpark, but it was new, fresh. A fresher take. People loved those players who retired, so to create them as an object, an icon, it seemed like a simple idea. And simplicity really is the key to most things.”

Ashton is sitting again now. I glance at his Earl Grey. No steam.

“There were so many things we did,” he continues. “That was a 24/7 project for six months. I wound up expanding [the company] a bit. I was teaching at the Maryland Institute. I was producing this large coffee table book on architecture. And I had to fight for a lot of stuff, but I had clients willing to go with me. Larry [Lucchino, the Orioles president], it was his idea to make this ballpark an old-type of ballpark, and Janet Marie, who was a young architect, agreed. And she’s brilliant.”

“Did it do anything to alter — or maybe reinforce — how you thought about design?” I ask.

“One thing it reinforced was if you do something you think is appropriate, even if it’s out there, and it works, you ought to keep doing that,” he says. “Also, your first idea usually is your best idea. I did talks all around the country after [Camden Yards] and I took pictures of the sketches and the completion, and they were so similar. It was the first idea. It came from the heart. It came from the soul. Not from anything else. And that’s probably the best place for it to come from.”

Ashton pushed to build the Camden Yards entrance sign with stainless steel, to match the rest of the ballpark.

To build the sign, Ashton turned to his friend and blacksmith Tom Moore, who would later construct the steel geese at BWI and help Ashton restore his home on Gentle Farm.

THERE’S A VIDEO Ashton’s firm produced about a decade ago. It’s a bit over two minutes long, with B-roll of Ashton and his staff at the office. Ashton does the voiceover.

“My whole life has been about design. … You think about what it is that is inside of these projects, what is the soul inside of them. That’s where the beauty lies — in the soul of anything.”

I’ve been meaning to ask Ashton about this. His description of the Camden Yards sketches — “it came from the soul” — reminds me of the video.

“Where does that perspective come from?”

He pauses, only for a few seconds.

“Being a country boy. I mean that’s simple, but it’s true. No bulls—. You’ve got to do what’s right. And I’m an artist more than anything. That was true when I was in high school doing the graphics and scrims for the plays. When I was [a child] I was making my own toys. I made clothes for my teddy bear, and I made little holsters with little cardboard pistols in them when I was like 6 years old.”

The key to revealing the beauty of anything, he says, is to become part of it.

“Find out what the soul is. If you do that, you’re probably going to come up with something.”

I’m thinking now about the farmhouse. I’ve never been there, but I’ve read about it. Ashton first saw what would become Gentle Farm in 1982. “It was a deplorable, horrible place,” he says. Today, house and property are a working canvas: rustic furniture, decorative stenciling and folk art on plaster walls, candleholders and iron door hinges made by Tom Moore, the blacksmith who built the home plate entrance sign at Camden Yards. Modern amenities like microwaves are hidden away wherever possible. The house is wired, but with the exception of the kitchen, it’s lit by candlelight. “I buy candles by the carload,” Ashton laughs, “and on any given evening this place is like magic.”

“It was the first idea. It came from the heart. It came from the soul. Not from anything else. And that’s probably the best place for it to come from.”

At its farming height, in the mid-1990s, Gentle Farm was home to more than 50 animals (sheep, horses, ducks, goats, chickens, dogs and cats), and Ashton faithfully dressed in period-appropriate, 19th-century clothing while working outdoors. He still does this, though not all the time. It takes him about four or five hours a day to tend to the horses and chickens that still live on the property.

It seems (to use Ashton’s word) appropriate, I say, that he returned the farm and house to its grandeur instead of tearing it down.

“Exactly,” he says. “We didn’t lower any ceilings or polyester any floors. Simplicity. Simplicity is the key to most things.”

By now it’s obvious that “simple” here isn’t a synonym for “easy.” The farm was a laborious undertaking — “[the house] was in such horrible condition; it took over a year just to get into it,” Ashton says. No, “simple” to David Ashton is something more devotional. It’s about being disciplined and detailed. It can be tedious. It’s authentic. Proper.

“Do you get that sense for simplicity from your Quaker upbringing?” I ask.

“Yes. Well, Quakerism, as you probably … ”

He stops.

“I don’t know if you know anything about it.”

“A little,” I answer sheepishly. Enough to know his answer would likely be yes, but not enough to fully understand why.

He smiles.

“When you went to Quaker meetings, you sat down on a long bench, for an hour, in silence. Can you imagine what that’s like? You can’t help but think about stuff in a simple kind of way. And then, if you think about something that’s important enough to share, you can break the silence. So people would get up and talk about something, and it had to be important enough to break the silence. That had to be something that got into my system.

“That’s the place where I took my first steps in life, in a Quaker meeting house. [It] was an 18th-century building, a beautiful thing. I was 9 months old, sitting with my parents, and all of a sudden I get up and walk down the aisle.”

David Ashton sits in the lobby of the Quirk Hotel in Richmond. (Jud Froelich)

DAVID ASHTON looks at his daughter. “Is my wallet here?”

All afternoon, Paris has been fishing magazines from her bag as a sort of show-and-tell complement to her dad’s stories: a copy of Communication Arts from 1992 featuring a piece about Camden Yards, the publication’s 50th anniversary issue that includes a note about a travel exhibit poster Ashton designed for the Smithsonian and a 1994 copy of Baltimore’s Style magazine with Ashton on the cover. He’s wearing Civil War-era American work clothes and, playfully, has a metal bucket over his head.

Paris Ashton hands her father his wallet. He reaches in, pulls out a card and passes it to me. It’s from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

“A lifetime pass,” I say.

“That cool?” he asks, rhetorically.

Seeing it reminds me of an unrelated question I forgot to ask earlier.

“You mentioned a book you were producing while you were working on Camden Yards.”

“It’s called ‘Domestic Views,’” he says. Ashton worked on the book with photographer Erik Kvalsvik. It’s about famous properties owned by Colonial-era women, and it’s one of Ashton’s favorite projects. I ask him to name some others.

“Well, a lot of them are books,” he says. “The first really good book I did was called ‘The Oystermen of the Chesapeake.’ Oystermen used to dredge for oysters under sail. There are still some who do it. Robert de Gast decided he was going to document this — their lifestyle, their boats, their families. This was 1970. And we did a coffee table book about that. It was in a slip-sleeve. It was a beautiful thing. It was my first venture into publishing.

“I did another book with him called ‘Western Wind, Eastern Shore.’ Robert circumnavigated the [Chesapeake Bay] and took pictures. And we did ‘The Lighthouses of the Chesapeake.’ It was one of [the American Institute of Graphic Arts] 50 Best Books the year it published.”

These projects almost seem like appreciations for the endangered everyday beauty we’re surrounded by and might overlook: natural wonders, workers toiling in a vanishing profession, the engineering marvels of yesteryear. I ask Ashton if he’s drawn to things in life that have that quality.

“I don’t know. I must be. Well, let’s face it, almost everything in my life is like that. My office was built in 1817. My home was 1840.”

“Even Camden Yards, you had this protective instinct about the warehouse,” I say.

“Absolutely. To be a graphic designer and have that side of it, it doesn’t really fit, because graphic designers pride themselves on being modern and ‘out there’ and ‘with it.’ I have all that, too, but I approach it from that earlier aesthetic. I like things to be beautiful and graceful.

“When I was a kid, my grandmother had a tourist home. Think pre-Airbnb. They had a little farm in Darlington, Maryland. Isn’t that a great name? They lived in an 18th-century log farmhouse. They were Quaker. And my grandmother ran this tourist home. I did the sign.”

“How old were you?”

“I was probably in my teens. I wish I had a picture of it. It’s all been torn down, so that’s very sad. But that’s life.”

Ashton, in a playful moment at Gentle Farm, placed a metal bucket over his head during a 1994 photo shoot with Baltimore Style magazine. (Jud Froelich)

It’s late afternoon now, and the hotel, sleepy when we arrived, is coming to life. The lobby bar is open. New guests are checking in. Outside, the sun has dipped beneath the gray blanket, and a few beams of light are visible on the building east of where we sit.

I ask Ashton how it feels to know that some of his work will not meet the same fate as that sign for his grandmother’s tourist home. There are books on coffee tables and shelves. Camden Yards is as beloved as ever. His sketches are in Cooperstown, in the hands of fellow preservationists.

“I don’t allow it to make me feel important,” he says. “That’s just something my family wouldn’t allow to happen. We are very modest. I guess that’s the answer. I’m just modest about it. I don’t toot horns. I may be tooting some here, but it’s only because that’s what you want me to do.

“The fellow that hired me at Barton Gillette, the head of the design department, his name is Ed Gold. He sent me a birthday message this year. He’s over 90 now. He said something about how great I’ve been and how modest I’ve been, and that I’ve left so many permanent things in Baltimore, all of which are great.”

Ashton pauses. I can’t be sure, but his blue eyes look a little misty.

“I wouldn’t ordinarily tell anybody that,” he says, “but I’m telling you that because you’re going to write something.”

He laughs. I ask him how he felt, reading Gold’s note. Ashton thinks for a second, then starts laughing again.

“I thought, ‘Eddie, are you bulls—ting me?’”

Ashton squints and tilts his head back slightly. Then he takes a breath and looks at me.

“It made me feel pretty good. I can’t be but so cavalier. That made me feel nice.”