Research & Discovery

Massey’s New Era

Amid a golden age for medical research, VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center has earned the most prestigious designation in oncology. What happens next will shape the future of cancer science.

Victoria Findlay’s double helix earrings gently sway as she leans forward in her chair. She’s explaining how advanced glycation end products ruin everything and how learning about them will help you live a healthier life.

Called AGEs, they are the result of a metabolic reaction in our bodies among sugar molecules and proteins, lipids and nucleic acids. Appropriately acronymed, AGEs are, effectively, one way our bodies get older. They turn flexible proteins brittle and make collagen lose its ability to regenerate. See small wrinkles around your eyes? That’s AGEs at work.

“It’s an aging process,” says Findlay, Ph.D., a researcher at VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Now imagine that process happening to all the organs in your body. That’s what makes us grow older and eventually die. It’s God’s fail-safe.”

AGEs amass in our bodies. They also are in food — annoyingly most abundant in meat, food caramelized with high and dry heat, and the ultra-processed goodies we devour for taste and convenience, like frozen waffles and packaged macaroni and cheese. Scientists have studied AGE accumulation in humans for more than half a century — mostly how it relates to Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. They’ve known about chemical reactions that create AGEs for even longer, thanks to the French chemist Louis Camille Maillard and his eponymous browning reaction (generated by heating sugars and amino acids and key to unlocking delicious flavors in everything from chocolate chip cookies to fried chicken).

And yet, frustratingly, the links between food consumption, AGE accrual and cancer (among other diseases) are understudied, Findlay says, because grant-awarding agencies like the National Cancer Institute have only in this decade formally recognized the importance of nutrition and lifestyle in cancer prevention. While we know a fair bit about how the piling up of AGEs in our bodies correlates to some diseases, we know little about how our diets influence AGE accumulation and even less about how a high-AGE diet can increase, say, our cancer risk.

Science suggests we can healthfully ingest about 15,000-20,000 units of AGEs per day. How much we consume fluctuates greatly, shaped by both what we eat and how we prepare it.

“[A] carrot has about two units of AGEs per 3 ounces,” Findlay says. “If you boil it, it goes to like five units. And if you roast it, it goes to about 20. So we’re pretty good with our vegetables. You take a raw chicken breast, 3 ounces, it’s got about 800 units of AGEs, just because it’s an animal product. No one eats raw chicken, so if you boil your chicken — which hardly anybody does — it goes to about 1,200-1,500 AGEs. If you grill it or roast it, it goes to about 8,000.”

Findlay is in her office. It’s a balmy and humid Tuesday in late June, the day after a bad storm. The tabletop is cluttered and a white binder with the words “Organized Chaos” stamped on the cover peeks from beneath a stack of documents. A rainbow of sticky notes are affixed to the southern edge of her computer monitor.

Getting here involves traversing a stretch of research bays on the third floor of VCU’s Goodwin Research Laboratory. Findlay studies AGEs as part of Massey’s cancer prevention and control program, which she co-leads. It’s home to 49 scientists who conduct research that helps people understand their cancer risk, educates them so they can lower that risk and improves the quality of life of patients, survivors and caregivers.

“Basically people know about fat, protein and sugar in food,” Findlay continues. “So when people want to be healthy they think about a low-fat diet or a low-sugar diet or watching the amount of salt they eat. And that’s all very good. But you can’t always eat low-fat and low-sugar and low-calorie. You want to eat things that are tasty. And some people try to be healthy and eat low-calorie TV dinners, or I always think of working mothers grabbing a cereal bar as they run out the door with a cup of coffee.

“The problem with all this ultra-processed food is AGEs aren’t regulated by the FDA. They aren’t on the side of packets. People don’t know they exist. But research supports that they may cause cancer, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, basically every disease associated with aging.”

Findlay’s four-person lab operates out of one bay. She shares a second with her husband, Massey researcher David Turner, Ph.D. They’ve been studying AGEs for more than a decade, previously at the Medical University of South Carolina and for the past 18 months at VCU. Turner studies how AGEs increase prostate cancer risk, and Findlay researches how they increase breast cancer risk. Outside the lab, they often visit churches and classrooms and speak at community events about nutrition and diet.

Theirs is a less-heralded wedge of cancer science, and though Findlay explains it well, it conflicts with our consumer-based society — and our palates. AGEs are added to processed food for flavor and shelf life, and the Maillard reaction (bacon, anyone?) is culinary school gospel. And how do you demonstrate that something you do prevents something bad from happening?

“You can easily take a patient and give them a drug and [say], ‘I cured your cancer,’” Findlay says. “But you can never prove that I made a change to your lifestyle and that’s why you didn’t get cancer. And that’s why cancer prevention has taken so long to get off the ground.”

But Findlay’s work is elemental to defeating cancer. Treating people for a disease is reactive. Saving people from a diagnosis (or from a recurrence) is proactive, and it’s one of the most important ways we can lower America’s cancer death rate in the coming decades.

Victoria Findlay, Ph.D., has been studying the relationship between what we eat and our cancer risk for more than a decade. (Jud Froelich)

AMERICA’S CANCER MOONSHOT, introduced by then-President Barack Obama in 2016 and rebooted in 2022 by the Biden administration, aims to cut cancer deaths in half by 2047. Its success relies on what happens in thousands of clinics and labs. But in essence, Moonshot hinges on better treatment, improved access to that treatment, eliminating disparities and boosting preventive health.

Since the 1970s, the U.S. government, through the National Cancer Institute, has spent more than $156 billion fighting cancer. Early detection screenings, a decline in smoking, an increase in HPV vaccinations and advances in medicine (especially in immunotherapy and antibody-drug conjugates that seek and destroy cancer cells without the harsh side effects of chemotherapy) have lowered the cancer death rate 33% since 1991.

Nonetheless, more than 600,000 Americans will die of cancer this year. It’s our second-leading cause of death, behind only heart disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disparities in access to treatment and survival rates — by race, income or whether someone has health insurance — hamstring our progress. Black men are nearly five times as likely to die of prostate cancer as men of Asian and Pacific Islander descent, according to a 2023 American Cancer Society study. West Virginia, which has the fourth-highest poverty rate in the country, has the highest cancer death rate — 52% higher than Utah, which has the nation’s second-lowest poverty rate and the lowest cancer death rate.

Of all the institutions that determine how the U.S. approaches cancer research and care, few are as influential as the NCI, the body empowered by the 1971 National Cancer Act to carry out a “war on cancer” by forming a nationwide coalition of institutes and providing guidance and research funding. In the half-century since, the NCI has designated 72 such institutions, classifying them (in ascending order of thoroughness) as basic laboratories, cancer centers or comprehensive cancer centers.

VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center has been an NCI-designated cancer center since 1975 (the year after its founding), and in June, the NCI elevated Massey to comprehensive status. There are more than 6,000 self-identified cancer centers in America. Only 56 are rated “comprehensive” by the NCI.

Robert Winn, M.D., Massey’s director, knows these facts as well as anyone. Achieving comprehensive status, he says, took decades of incremental progress and financial backing from the state government, VCU Health and tens of thousands of donors. Today, approximately 85% of Massey’s $41 million operating budget comes from those three sources. “Without all that, we wouldn’t be claiming comprehensive status,” Winn says. “People ask, ‘How hard is it [to be comprehensive]?’ We’ve been working at it since 1974. It’s very hard.”

Here’s why: To be comprehensive, a cancer center must prove four things. The first is a robust research portfolio. The second is team science. (It isn’t enough for a center to have dozens of researchers with individual grants. To be comprehensive, an institution must show how it brings together, say, a biomedical engineer, a physician and a data scientist on one study.)

Criterion No. 3 is engagement — the in-the-neighborhood work Victoria Findlay and David Turner are doing when they aren’t in the office. Comprehensive cancer centers must demonstrate community symbiosis, sharing what they learn and incorporating community needs into their research. This means conversations with people about the things that, directly or indirectly, increase their cancer risk, like their hobbies and diets, whether they have trouble accessing medical care and whether they live near a grocery store or in a neighborhood with more crime or pollution.

Fourth, a center must prove it prepares the next generation of scientists. The best cancer centers host programs that train students, some as young as middle school, in cancer research.

An aspiring comprehensive cancer center must document this every five years in a grant application known as the P30, a brick of a document that takes about nine months to put together. At VCU, that task falls to a six-person team led by Anita Harrison.

“The cancer center has to tell a good story,” Harrison says. “It has to tell why it’s worthy of comprehensive status.”

Harrison is speaking via video on an early July Friday. Her official title is executive director for research strategy. She came to Richmond in May 2021. A grant writer by trade, she’s worked at NCI-designated cancer centers for three decades — at Wake Forest, the University of California at San Francisco, Washington University and, with Findlay and Turner, at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Robert Winn brought Harrison to VCU to help Massey achieve comprehensive status. She’s explaining how it happened.

“So the grant is … well, let me just show you.”

Harrison disappears into her Zoom background. A few seconds later, she returns, having pulled, seemingly from hammerspace, a book hefty enough to activate a seismograph.

“Can you see this? This is the grant. It’s 1,800 pages.”

Here’s the story she wrote on all that paper: Since its last P30 in 2016, Massey quadrupled its number of team science grants. It went from two next-generation training programs to seven. It was selected to lead a $114 million project to increase diversity in clinical trials.

Winn, now in his fourth year at VCU and at the time of his hiring the second Black cancer center director in U.S. history, also tapped into one of Massey’s founding ideals. In 1976, the fledgling center produced a document introducing a community outreach program, outlining the responsibility it had “to meet the needs … defined by the regional health care professionals and the lay public.”

Community engagement has been a Massey hallmark ever since, and Winn turbocharged it. Today, it has its own office, headed by Vanessa Sheppard, Ph.D., a population scientist and expert in health disparities.

Once a month, Winn — a bow tie enthusiast who still runs his own lung cancer lab — laces up his walking shoes and, with a group of colleagues and a local lawmaker, visits a neighborhood in Massey’s “catchment area,” the official term for a cancer center’s surrounding community (VCU’s is, roughly, the eastern half of Virginia). Early in the pandemic, Winn hosted conference calls with Black clergy to debunk COVID myths. Those blossomed into a community series, Facts & Faith Fridays. Guests have included first lady Jill Biden, Ed.D., Anthony Fauci, M.D., and former NIH Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D.

“I mean, he just transformed this cancer center and what its roles and responsibilities and accountabilities are to the community,” Harrison says. “That’s a scorable component on [the P30]. And we received an exceptional rating in community outreach and engagement.

“This is Dr. Winn’s superpower. There’s no cancer center director in the country that takes a day out of their schedule every month to go walk in the community. But he does.”

Robert Winn, M.D., visits a neighborhood in Chester, Virginia, in July. Once a month, the Massey director, joined by colleagues and often a local lawmaker, meets with residents who live in Massey's “catchment area,” the official term for a cancer center’s surrounding community. (Tyler Trumbo)

THE SCREEN FLICKERS and Robert Winn appears. It’s late July now, the mercury outside inching past 90 degrees. Winn, in his office, has eschewed his sartorial trademark in favor of an open-collar blue Oxford dress shirt and navy blazer.

Like many of his peers, Winn has a few titles beyond “director.” He’s the Jeanette and Eric Lipman Chair in Oncology at Massey, senior associate dean for cancer innovation and a professor of pulmonary disease in the VCU School of Medicine. He came to Richmond after five years at the University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago.

Winn runs a center that painstakingly pursues a future without cancer. His philosophy on how to get there: a thorough understanding of both disease and humanity. Massey retooled its mission statement shortly after he arrived — “it’s long and breaks all the rules of what a mission statement should look like,” Harrison says, laughing. But it’s also illustrative, aiming to reduce the “cancer burden for all Virginians” by tackling cancer’s “biological, social and policy drivers” — not just science, but how laws, where a person lives, how much money they make and their access to basic health care shape their cancer risk.

“One of the things we recognize is that biology — whether you’re African American, Asian, Latino, white — is influenced by place and space, which is one of the reasons why we have as much interest in the cancer health of folks that live in Lynchburg or Martinsville or Danville or smaller communities,” Winn says. “Having the data that supports why, for example, one drug works in one person and not in another is important. And I think, in understanding those places that are most vulnerable and those patients that are not doing well: Is it an access issue? Is it a biology issue? Is it both?”

These questions are foundational for the cancer centers that treat patients and conduct research. In the coming years, Winn says, Massey’s Molecules to Medicine Program is “all-in” on identifying a molecule (naturally occurring or synthesized) and using it to build and test a new cancer drug. In cancer prevention and control, researchers M. Imad Damaj, Ph.D., and Oxana Palesh, Ph.D., are studying, respectively, peripheral neuropathy and brain fog, two debilitating side effects of chemotherapy. Some cancer treatments can cause heart damage; Massey scientists and colleagues at VCU Health’s Pauley Heart Center are designing ones that don’t.

Palesh, a psychiatrist and co-lead (with Victoria Findlay) of Massey’s cancer prevention and control program, came to VCU in 2022 from Stanford. Her arrival foreshadowed one of the biggest benefits of comprehensive status. Chiseled to its core, the most prestigious institutional honor in oncology is an industry laurel, like a renowned restaurant earning its third Michelin star. Today, Winn says, Massey is in a better position to recruit scientists from other elite institutions. The center will likely lead and participate in more clinical trials. Regions with comprehensive cancer centers, such as metro Boston and the North Carolina Research Triangle, often become pharmaceutical and biotechnology hubs.

“It’s kind of a magnet,” says Thomas Loughran, M.D., director of the University of Virginia Cancer Center.

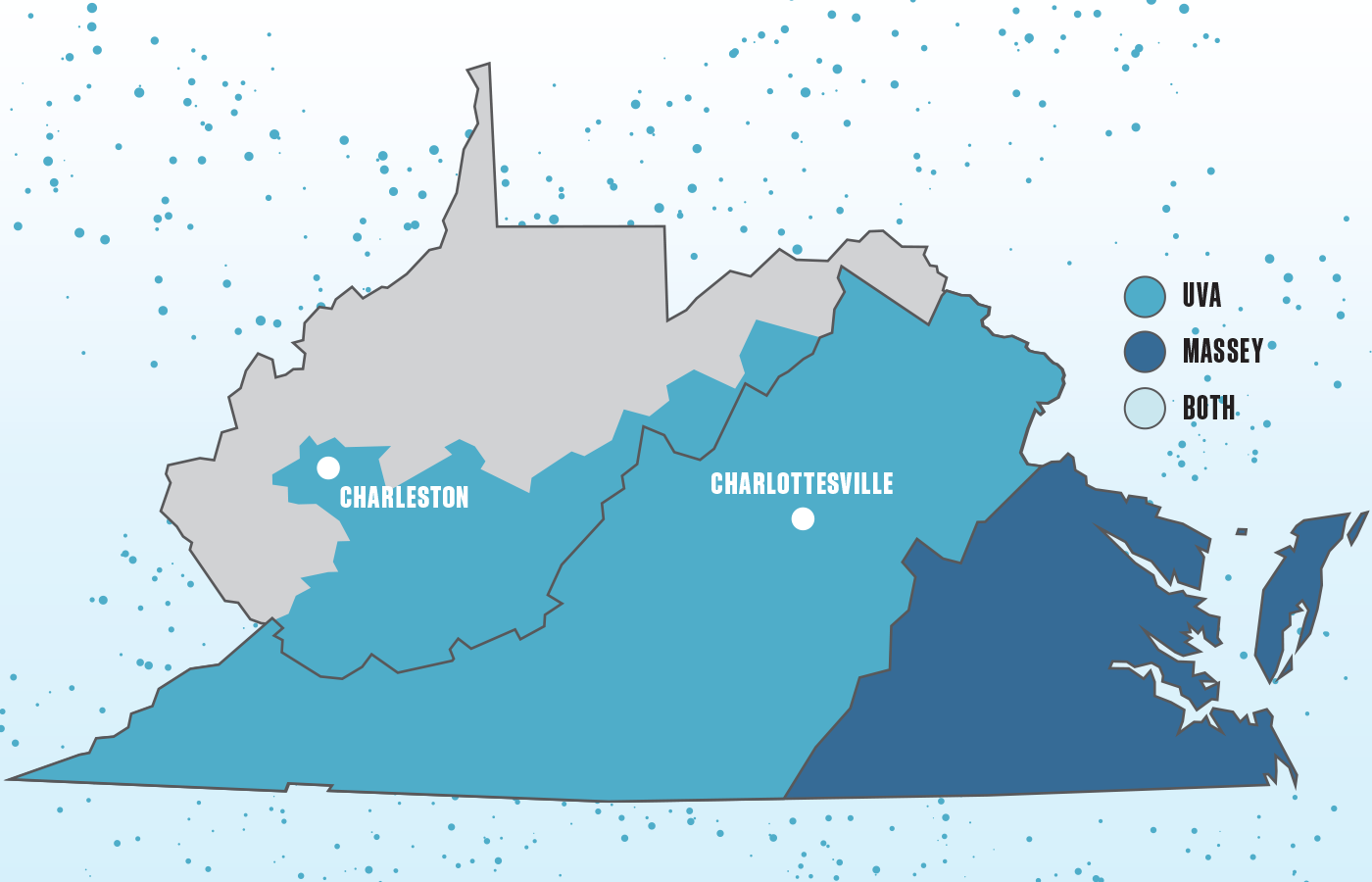

UVA achieved comprehensive status in 2021, and since then, its patient referrals are up 15%. Massey and UVA becoming comprehensive together is “a momentous achievement for Virginia,” Loughran says. Only 11 comprehensive cancer centers are in the Southeast, and the Old Dominion, which had zero, now claims two. Their catchment areas are home to more than 6 million people.

“The governor and the legislature about 10 years ago started funding both Massey and ourselves with the idea that they wanted to get at least one of us at the higher level,” Loughran says. “And so to get two at one time is just unbelievable.”

It comes at an inflection point in medicine, he says. Breakthroughs in nanotechnology (the delivery vehicle for the mRNA COVID vaccines) and artificial intelligence, combined with two decades of knowledge since we first mapped the human genome, could usher in a golden age of cancer science. Winn says he’s hopeful that in the coming years we’ll see vaccines to treat solid-state tumors, the eradication of cervical cancer (thanks largely to HPV vaccines) and more tests and therapies that can be delivered to patients in their homes.

Harrison disappears into her Zoom background. A few seconds later, she returns, having pulled, seemingly from hammerspace, a book hefty enough to activate a seismograph.

“Can you see this? This is the grant. It’s 1,800 pages.”

The future he and Loughran describe is one of discovery and research, begetting techniques that make Moonshot a reality. Nearly two years into the reboot, America is pacing to reduce cancer deaths 44% by 2047. Getting to 50% and beyond requires a concerted effort, from turning a molecule into a drug to Damaj and Palesh studying the side effects of current treatments to Victoria Findlay and David Turner toiling away in their adjoining offices.

Some of the most vital advances will happen by slashing health disparities. One way to do that: clinical trials that are less homogenous. For example, about 14% of the U.S. population is Black, but Black people accounted for only 8.5% of oncology trial patients from 2010 to 2021, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Lacking a fully representative sample, drugs are approved without knowing whether they are equally effective for all patients.

“The FDA approved a combination regimen for endometrial cancer in 2021,” Anita Harrison says. “High representation [of disease] among Black women. Of the registrational trial, and there were thousands of patients, only 4% were Black. And now it’s being discovered that Black women are not able to tolerate this treatment as well as white women. And they don’t know why. And now they’re having to go back and do the research because Black/African American women were underrepresented in the clinical trial.”

We’re making progress, Harrison says. Slowly. Moonshot includes funding to study and reduce disparities. And the makeup of the nation’s comprehensive cancer centers has changed. UVA’s catchment area includes 13 counties in West Virginia. Massey and the University of Kansas Cancer Center (named comprehensive in 2022) are NCI “minority/underserved community sites” because at least 30% of their patients are racial minorities or from rural communities.

Between July and October, Harrison filed eight research grants for funding. All were focused on health disparities.

“If we’re going to really move the needle for Moonshot, we’ve got to move the needle on improving outcomes for Blacks and [in] rural America,” she says. “America has greatly reduced lung cancer incidence and mortality over the last 50 years. But where do we still see huge disparities? Twenty-four percent of adults still smoke in Petersburg [Virginia]. So it’s not surprising that we see higher lung cancer incidence and mortality in Petersburg.

“To me, it’s all about prevention and control and community engagement. I’m not suggesting that we stop our cancer discoveries and stop finding better drugs and immunotherapies. We’ve got to continue that. But it’s all about risk reduction. That’s how we’re going to get to the [Moonshot] goal line.”

There are more than 6,000 self-labeled cancer centers in America. Only 56 are rated “comprehensive” by the National Cancer Institute. Two are in Virginia: University of Virginia Cancer Center and VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center. The communities they serve, shaded in the map above, are home to more than 6 million people.

BACK IN HER office, Victoria Findlay is explaining intermittent fasting, a diet that restricts when you eat, not what, by scheduling times to eat and fast.

It’s connected to health benefits ranging from a leaner body to improved blood pressure. Findlay does it and raves about it. She now eats only between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. Her lab is studying whether intermittent fasting can lower breast cancer risk among prediabetic, postmenopausal women, even if they have a high-AGE diet.

Findlay was introduced to this through a colleague at the Medical University of South Carolina. What she likes most about intermittent fasting is it’s more equitable — requiring little more than a clock and discipline — compared with diets that overhaul a patient’s pantry.

“It’s like, ‘I’m going to stop you from eating [this] for six weeks, and your risk is going to go down, and then I’m going to stop helping you and you go back to eating exactly what you were eating,’” Findlay says, shaking her head. “That’s not where we need to be. [If] you tell someone to stop eating carbs, they’re going to live and die thinking about carbs, and eventually they’re going to sit down and eat, like, pasta with a side of fries wrapped in a loaf of bread, right? And then they’re going to feel miserable and start again.

“And you have to think about how not everyone can achieve these changes. You can’t just make everyone go out and buy a ton of groceries that are really healthy. Some people can’t afford it.”

This is where Findlay the mother, Findlay the scientist, Findlay the health coach and Findlay the equity advocate come together.

“How do I inform parents so they can inform their children so [those children] can have children and inform them? And so telling someone that they have to go to a grocery store that they can’t get to, to spend $200 they don’t have, on food they don’t recognize, it’s absolute total failure, right?

“But if you tweak your diet, you can sustain that. Something like [intermittent fasting] doesn’t cost anything [and] if you can get people doing it in a three-month trial, by the time they’re at the end, their body becomes used to that eating pattern. We’re not grazers. If you tell someone to only eat within a certain window, but they can eat whatever they want, they’re not feeling like they’re being deprived. Their body adjusts.”

It’s not easy to make wholesale changes, Findlay admits, but it’s also not impossible to layer these “tweaks” by, say, fasting intermittently, cooking a vegetarian meal a few times a week or marinating chicken in a Ziploc bag with lemon juice before you cook it (the acid reduces AGE formation). Findlay plans to write a low-AGE cookbook. She and Turner started a nonprofit, the Anti-AGEs Foundation, in 2020 to share information about the hazards of processed foods.

It’s a long game. They are parents to 9-year-old twins, whose art — along with the sticky notes — injects a little color into Findlay’s office and illustrates why she does the work.

“We don’t want to scare everyone and tell them everything is bad. I still take my kids to eat fast food. We [just] do it every couple of months,” she says. “But people can’t choose to avoid [AGEs], because they don’t know they exist. So we try to educate people about the basics of cancer and the basics of risk and talk to you like normal people. Don’t call me Dr. Findlay. I’m Vick. Tell me about what you eat. Tell me about your lifestyle. Tell me how I can help.”

Findlay leans forward in her chair again. Over her left shoulder, a single window offers partial views of Shockoe Valley and Union Hill.

“Massey was talking about cancer prevention and community outreach in 1975, and this is why I think comprehensive status is so important,” she says. “A lot of cancer centers from the larger institutes were super strong in impactful science [but] that was completely incommunicable to who it was actually going to help. They were just really great scientists who were going to win Nobel Prizes and get loads of papers [published]. And then they were like, ‘Oh, the community is important. We should do community outreach now. How do we do that?’ Whereas [Massey] always said, ‘We understand the community is important. That’s where we want to be.’ And now you’ve got a place that’s doing really great science and also is able to apply that to the community, and the community buys in because they see the people who are doing it.

“[I] cannot overstate the importance of [achieving comprehensive status] and what that means. People look at you differently. Are people suddenly better because they’re at a place that has comprehensive status? No. But being recognized for what you do because of where you are means something. And if it means my work gets more recognition, that means I’m helping more people. That’s why I feel so empowered now, because I feel like with a brighter light shining on us, I’ll have a bigger stage to share what we do.”