Arts & Culture

A Sense of History

Author Rachel Beanland (M.F.A.’20) balances modern tastes and historical accuracy in her new novel, “The House Is on Fire.” In this story and annotated excerpt, she explains how.

Writing historical fiction is mostly about using imagination to fill in where the historical record turns useless.

Working on a YA paranormal romance about Julius Caesar? History has enough on the ancient Roman general to fictionalize a plausible Caesar, even if he’s falling in love with a sparkly vampire.

The challenge, says author Rachel Beanland (M.F.A.’20), would be making this Caesar acceptable in two eras: his and ours.

“We’re writing something that we want to come off just completely authentic to the day, right?” Beanland says. Her new novel is set in 19th-century Richmond, “but it’s going to be read by people who live in 2023.”

Published in April by Simon & Schuster to praise from The Washington Post and NPR, among others, “The House Is on Fire” is Beanland’s second novel, following 2020’s “Florence Adler Swims Forever.” Both are historical fiction.

Written in straightforward prose, “The House Is on Fire” follows three survivors and one observer of 1811’s Richmond Theatre fire. It killed at least 72 of the 600 or so people in the audience, including Virginia’s governor, seeing two plays on the night of Dec. 26. Monumental Church, completed in 1814 as a memorial to the fire’s victims, who are entombed beneath it, stands where the theater did, just across East Broad Street from the state Capitol.

“If I had written a book featuring nothing but characters who knew their place in society and didn’t push up against the boundaries of that society, I think people in 2023 would want to throw that book against the wall,” says Beanland, a graduate of the creative writing program in the College of Humanities and Sciences. “There’s this balance you’ve got to achieve, I feel like, with historical fiction where you say as the author, ‘I’m aware of what was happening then, but I’m also going to give you some characters that are questioning the world around them.’”

The character most serving this purpose in “The House Is on Fire” is Sally Henry Campbell, an imagined iteration of a real-life daughter of Patrick Henry. (By 1811, he had experienced both liberty and death.)

Sally, a 31-year-old widow, acts gallantly during and after the fire, as does Gilbert Hunt, an enslaved blacksmith, whom Beanland based on a real person. (The historical Gilbert Hunt eventually bought his freedom and became a deacon, dying in 1863.) The fictionalized (but, as much as possible, historically plausible) versions of these people in the novel exceed the expectations of their social station.

Gilbert’s actions during the fire are documented. He saved about a dozen white women, catching them as they were passed from a theater window. What Sally did is unknown, but the story Beanland gives her isn’t improbable.

“I really wanted someone who had a window into how the men had behaved on the second and third floors, which by all accounts was not great,” Beanland says. “I needed someone who was capable of noticing, of paying attention. Would she really have thrown a big fit? Would she have written it off herself and been, ‘Oh, like, there’s an explanation for this?’ Who knows?”

In a scene after the fire, Sally debates which medical treatment is best for a friend, a woman who is injured escaping the theater. Sally’s debating this with her friend’s husband, who is useless. But as a man in 1811, the husband has the final say over his wife.

Because Beanland keeps everything 1811-appropriate, Sally cannot and does not do anything about the husband’s blithe decision. But thanks to the omniscient narrator, we know what Sally’s thinking. She is, let’s say, vigorously miffed.

“Sally’s a feminist, but I don’t have her completely bucking the system,” Beanland says. “Gilbert’s enslaved and he is a hero, but he is not going to suddenly partner with someone like Sally and go off [with her] and try to do something to help people, right? I wanted to, as much as possible, keep the characters in their lanes, with the understanding that these characters in many cases would have not interacted together. They wouldn’t have had control over their destinies. They could control individual choices that they make.

“Sally can decide to go back for [her friend] or not, but she can’t decide to not ever marry again and to somehow buck the whole system of marriage, because the reality is, as a widowed woman in 1811, she had no freaking options. None. The plight of a widowed woman, even when you’re coming from means, was like you were completely beholden to your parents, your brothers, your extended family to host you. There was no safety net for you, really. So that’s just something I was always really conscious of — not creating, I guess, false narratives. She can think all the things. She just can’t do them all.”

Beanland moved to Richmond in 2007 and learned about the theater fire on her first day here. A real estate agent touring her around the city mentioned it as they passed Monumental Church, giving her the short version of the calamity that became an international cause célèbre of the time. Today, even in Richmond, the fire is mostly forgotten.

“I think I just turned 27, a long way from writing my first novel,” Beanland says. “But I was a huge reader and I was always writing something, and I just thought, That is a story. It just struck me as being infinitely interesting.”

The idea lingered. Settings, Beanland says, serve as her best muses. Then she sculpts her stories from a slab of time and place with extravagant amounts of research, logged by hand in composition notebooks and later organized in Word documents.

“Most fiction writers will tell you everything starts with character, that they picture a character,” says Beanland, who wrote “The House Is on Fire” while homebound in Richmond during the pandemic. “They start thinking about what that character would do, how that character would respond to certain obstacles and whatever, then everything else builds out from there. I think I’m a little bit different in that regard. I do think about character early, but I think about setting an awful lot. I really want the right setting for a story, but I also sometimes want the right story

for a setting.

“When I’m thinking about setting, I feel as if that may come from the fact that I moved around so much, that I wasn’t from one place.” Beanland is a Navy brat. “Because I do have this innate feeling that where you are has just a huge effect on what becomes of you. You might have grown up as one kid being raised in Richmond and as another kid being raised in D.C.”

For “The House Is on Fire,” Beanland relied on accounts from the Richmond Enquirer, a newspaper that operated from 1804 to 1877 and whose editor in 1811 is a character in the novel. She also used memoirs, the archives at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture and the Library of Virginia, and the wonderfully esoteric “The Richmond Stage 1784-1812” by Martin Shockley to finesse the necessary verisimilitude. Part of that is language.

“You’ve got to say, ‘OK, let’s make a deal’ — the reader and I,” Beanland says. “In 1811 they were speaking, approximately, like the newspaper articles you’re reading in this book, but you don’t want to read that for 383 pages or whatever, and so how can I achieve that feel while also giving you what you want to read in 2023? For me, it looks a lot like reducing my use of contractions and throwing in individual words that were used at the time.”

There are no known accounts of the Richmond Theatre fire from Sally Henry Campbell, who remarried in 1813 and died in 1856.

We, however, do have accounts from other women who survived the fire, some of whom jumped from second- and third-floor windows, risking death by falling to avert death by burning.

“Even when people write their firsthand accounts, there’s so much formality to what they’re writing,” Beanland says. “We know a lot, but we don’t know what they were thinking and feeling, and if you go into it thinking each of these people is a human being — and that’s hard to do because they lived so long ago. It just feels like, no, they’re portraits on the wall, not real people, right? But if you can convince yourself they were real human beings, and just like us they had things that [ticked] them off and things that brought them great joy and pet peeves and all the rest of it, then it does become really fun to figure out, Well, what they would do in this situation?”

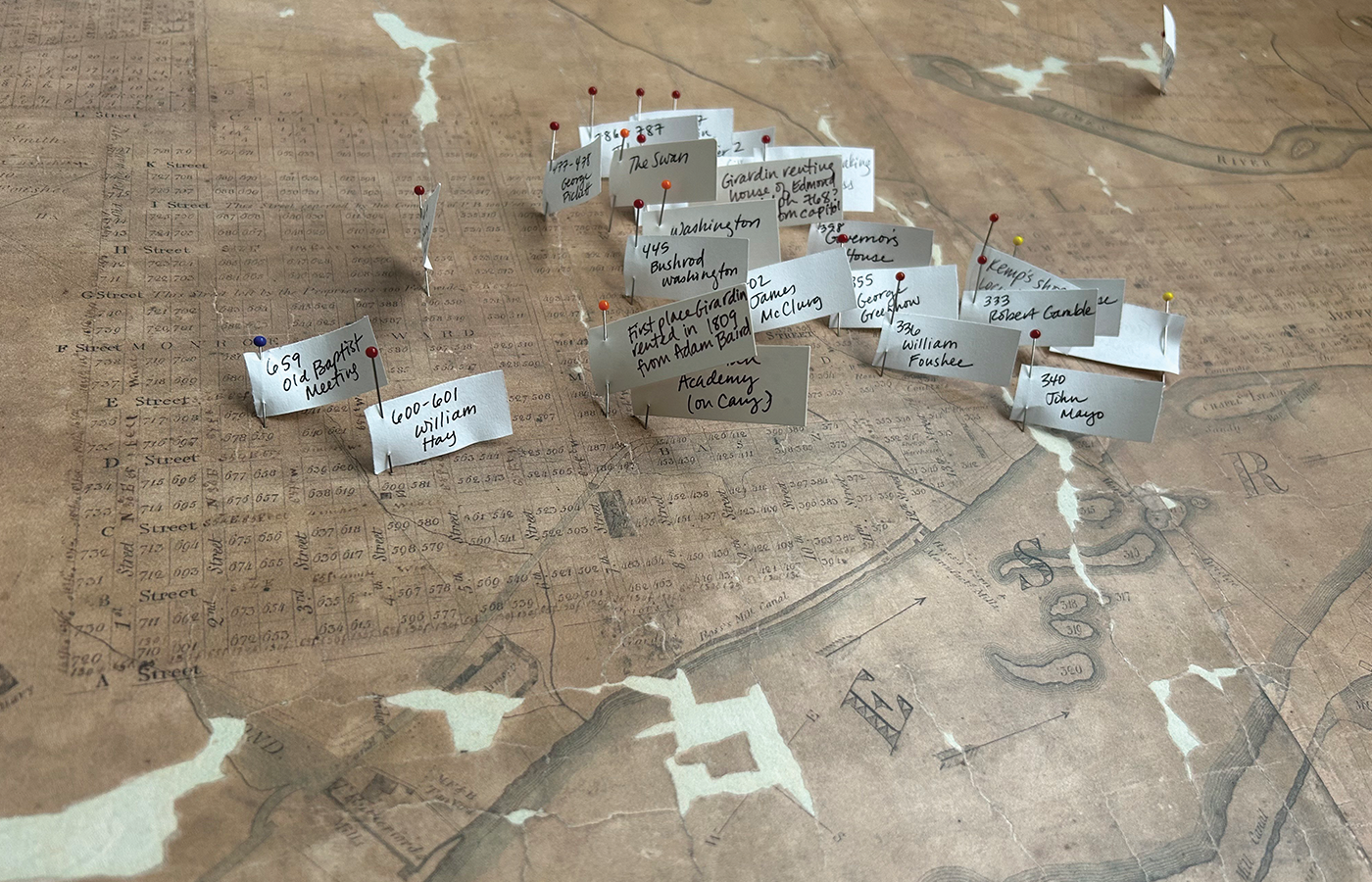

Rachel Beanland made this pushpin map of early 19th-century Richmond to help her with the geography of the era while writing her novel. (Courtesy of Rachel Beanland)

To give readers a peek into her writing process, author Rachel Beanland annotated a portion of her new novel, “The House Is on Fire.” In this chapter, written from a young stagehand’s point of view, the fire starts.

Jack Gibson waits for his cue. As soon as the commodore delivers his last line and exits stage right, Jack is to run, quick as he can, and prepare the set for the play’s final scene.

This opening didn’t change at all … from my first draft to the book you hold in your hands.

When the theater company’s artistic director, Alexander Placide, pulled everyone together earlier this month to announce that the company would stage Louis Hue Girardin’s translation of The Father, the actors had groaned. Shakespeare, Goldsmith, and even Sheridan were crowd-pleasers, but according to the troupe’s old-timers, Diderot was nowhere near as popular. “The French can’t hold a candle to the Brits,” shouted one of the actors, William Anderson, as Mr. Placide prepared to distribute parts.

This is a relatively simple sentence, but writing it required hours of research on 19th-century theater.

Placide is French and smart enough to know when he’s being lampooned. “Mr. Anderson,” he said in his thickly accented English, “if you have such an affinity for the British, you’re more than welcome to return to that fair isle. Please give King George my regards.” That got a good chuckle out of everyone, and most of the actors accepted their parts without further complaint.

I had a lot of fun playing around with the idea that, in 1811, the United States’ relationship with England was still evolving.

“Placide is brilliant,” Anderson explained to Jack later. “Diderot’s plays are no good, nothing compared to his essays, but it’s Girardin and not Diderot who will pack the house. People love supporting a local talent.”

Anderson is right about everyone in Richmond loving Professor Girardin. Jack, for his part, adores him. Girardin runs the Hallerian Academy, which Jack attended until two years ago, when his father got sick. Jack’s mother had died in childbirth, so after his father was gone, Jack went to live with his uncle Douglas, who wasn’t the least bit interested in raising a child, much less paying his school fees. Thankfully, Girardin continued to loan Jack books and periodicals and to invite him for supper, and last winter, when things got bad at his uncle’s place, Girardin had offered him a bed in a cottage at the rear of his property. “Just until you can find a more suitable position,” he said as he showed him where to shovel the coal he’d need for his stove.

This paragraph got rewritten a hundred times. Mainly because Jack’s backstory kept changing. I wanted him to have a close relationship with Girardin, who was a real figure in Richmond at that time, and I also wanted the theater company to have plenty to hold over his head.

The arrangement lasted the better part of a year, until October, when one of Placide & Green’s stagehands quit, and Girardin convinced the theater’s manager, John Green, to interview Jack for the position. Jack had always dreamed of a career on the stage, and here was a chance to get his foot in the door with one of the best theater companies in the country. In the interview, he tried to convey his unbridled enthusiasm for the role, but his audience with Green was disturbingly brief: Green wanted to know if Jack could carry a quarter barrel and tie a bowline knot. Then he asked if Jack had a problem with heights, and when Jack said no, Green told him he was hired.

When I teach writing, I always tell my students to get as specific as they possibly can. Specific details make what we’re writing believable.

The job pays two dollars a week and comes with room and board at the Washington Tavern, which is where most of the unmarried actors stay when the company is in town for the season. But the best part of the whole arrangement—by far—is that Jack gets to read all the plays he wants. Three nights ago, while the company got oiled in the Washington Tavern’s back room, Jack snuck a copy of The Father upstairs and read every word of it by the light of the moon. As soon as he was finished, he read his favorite scenes again.

I’m always looking for words and phrases that can help me denote the time period.

At fourteen, Jack is hardly a literary critic, but he thinks this Mr. Diderot tells a nice story. The main character is a kindly father named Monsieur d’Orbesson, who spends much of the play trying to decide whether to grant his son permission to marry a girl of no means. The way Jack figures it, d’Orbesson loves his children dearly, and his only flaw, aside from trusting his no-good brother-in-law, is that he thinks he knows better than his children what will make them happy.

Of course, for research, I had to read “The Father,” which was performed the night of the fire. It was a nice bonus that some of the play’s themes connected back to Jack’s storyline.

From his position in the wings, Jack is able to peek out at the audience. He’s struck by how crowded the theater is. The gallery is practically bowing under the weight of so many bodies, and the boxes are packed. Even the pit seems particularly rowdy.

“My baubles are turning to icicles,” says Thomas Caulfield, who is stuffing his hair under a rather ridiculous pompadour of a wig. “Can we not get so much as one stove back here?”

All the actors ever do is complain. To Mr. Placide, they complain about their parts and the price of their costumes. To Mr. Green, it’s their pay. To Jack, they complain whenever he fails to put a prop or costume piece away, or if—in putting the item away—he makes it harder to find. To anyone who will listen, they complain that the managers have moved all the available stoves into the auditorium to keep the audience from freezing to death—at the expense of the actors backstage.

Jack tries never to complain. He has worked any number of odd jobs since he quit school, and this one is by far his favorite. He likes all the hubbub backstage and the easy way the actors rib each other—like they are part of a big family—and he is convinced that if he works hard and shows he can learn, the company will take him back to Charleston at the end of the season.

Every character needs to want something. That want is what drives their decisions and also motivates readers to keep turning pages. The reader wants to find out if the character will get what they desire. So, this line is important because it gets at the heart of what Jack wants.

“Kid,” says Anderson, nodding his head in the direction of the stage, “you missed your cue.”

Jack springs to attention and sprints onto the stage, repositions a handful of chairs and removes a small table. When the set looks approximately as it did during rehearsals, he scuttles offstage again.

“Watch it,” says Billy Twaits when Jack skids into him. Twaits, who is tall and broad enough to make an intimidating commodore, isn’t someone Jack wants to upset. “Sorry, sir,” he says quickly, ducking behind one of the stage flaps, where he hopes he won’t draw any attention. He takes his official orders from the theater’s managers, but it is hard not to do the actors’ bidding, too. And if he is sent off on some errand right now, he’ll miss seeing the grand reconciliation between d’Orbesson and his three children.

One of the challenges with this chapter was that, because we’re backstage, I had to introduce a slew of characters to the reader all at once. Whenever possible, I tried to give the actors and stage crew distinguishing attributes.

In the final scene, d’Orbesson banishes the commodore from his home, then gathers his children around him. “I will do everything that I can for the happiness of all of you,” he says as he gives them his benediction. Jack is impressed with Mr. Green’s performance—he really does come off sounding like a devoted father—and, for a moment, Jack misses his own father so much, it hurts.

A paragraph like this is doing a lot of work. I’m both telling the reader what is happening and also what Jack thinks about what is happening. There's even a tiny bit of backstory woven in.

The play ends, and a loud round of applause swells from the audience. The senior stagehand, Clive Allen, lowers the drop curtain, and while he and Jack and a few other members of the crew ready the stage for the pantomime, they can hear Tommy West’s baritone, accompanied by a plucky fiddle, on the other side of the curtain.

The audience expects the company’s musical interludes to be raunchy, but West has outdone himself this time. The song’s lyrics are so crude that, at one point, Jack laughs out loud. Placide, standing nearby, shoots him a stern look, and Jack claps his hands over his mouth.

“Perry!” says Anderson when the carpenter walks past, carrying a faux stained-glass window. “Did you get a chance to look at the chandelier?”

“Briefly,” says Perry, who isn’t a machinist, but is the closest thing to it. “It looked all right to me.”

“It’s the pulley,” Anderson says. “Goes up fine, but when I tried to bring it down, it just rode in a circle.”

“What were you doing bringing it down?” says Clive, who never likes the actors trying to do his job for him.

“Excuse me for lending a hand,” says Anderson, and stalks off.

Figuring out who did what, backstage, during the fire took me a long time. Particularly because the inquest report is really vague on some of the most important details.

Placide, who is playing the Baptist in the pantomime and has been fussing with the belt of his costume, overhears the discussion. “Is that pulley giving you issues again?” he says, and while Clive fills him in on the situation, Perry hurries off to install the window.

“Doesn’t matter how gently I release the rope,” says Clive, “it pops right off the wheel.”

The chandelier’s pulley hasn’t given Jack any problems, and if he were a more established member of the company, he might say so. The backdrops actually give Jack the most grief. Each backdrop—and the theater company owns nearly three dozen of them—is fifteen feet high and nearly twice as long. They’re made from bolts of hemp, which are stitched together and painted on at least one side, if not both. There is a bucolic village, a medieval city, a farmyard, and a seascape, not to mention a forest and a castle interior, which Jack remembers that he needs to cue up for the pantomime.

The bottom of each backdrop is secured to a heavy, round batten, and it falls to Jack and Clive to raise and lower the unwieldy buggers using another system of pulleys installed in the rafters. Provided Jack can get Clive to count off and ease the ropes at a steady pace, it is possible to use the pulleys effectively. But if anything goes wrong, or if Clive can’t be dug up, Jack must scramble up into the carpenter’s gallery to release the backdrop manually. Whenever he does this, the bottom of the backdrop hits the stage floor with a loud crash that shakes the stage boards and startles the crew.

This is another paragraph that didn’t change much from the first draft to the last. It’s nice when that happens, although it’s rare!

From Jack’s perch in the carpenter’s gallery, among cut-out clouds and stars, a sun, and three moons, he can hear Mr. Placide’s daughter, Lydia, take the stage for the sailor’s hornpipe. Lydia is only a couple years older than Jack, but she is a good four inches taller than him, with a smile that never leaves her face and breasts that bounce up and down when she taps her feet to the fiddle music. She runs around with Green’s daughter, Nancy, and Jack is too scared to talk to her most all of the time, but he loves to watch her dance. Even now, with Lydia on the other side of the curtain, he can feel the pounding of her hard shoes on the stage floor, and the vibrations make him heartsick. As the song reaches its crescendo, Lydia’s feet begin to fly, and the audience’s applause is thunderous.

As soon as I wrote this line, I knew Jack was in love with Lydia.

This is the view from the gallery in Monumental Church, a National Historic Landmark which was an Episcopal church until 1965. (Jud Froelich)

“Oy, Jack,” says Clive from the bottom of the ladder that leads to the carpenter’s gallery, “help me out down here.”

Once the pantomime is underway, Jack doesn’t stop running. There are backdrops to be swapped out, set pieces to move, props to place. And, as usual, none of the actors can do anything for themselves. Caulfield thinks he’s meant to be carrying a sword, but there was no mention of one during rehearsals; West has misplaced the shoe polish he’ll use to blacken his face for his role as the old servant; and Mrs. Green, who will soon take the stage as the bleeding nun, can’t find the bladder of pig’s blood Jack specifically set aside for her. “Have you looked in the back?” he asks, but he doesn’t wait for an answer. It will be quicker to find it himself.

In my first draft, I had a whole paragraph summarizing the plot of the pantomime. My editor suggested I cut it, and she was absolutely right.

The bladder is sitting in a pail near the stage door, and when Jack takes it to her, he watches—enthralled—as she cuts a tiny hole in the thin membrane with her teeth. It takes only the slightest pressure for the viscous liquid to stream onto her white frock, and the effect is so gruesome, Jack begins to feel a little light-headed.

“How do I look?” she asks when the job is done, and it’s all Jack can do to nod his head and say, “Bloody marvelous.” That gets a laugh out of her.

Mrs. Green has become an almost mythical figure in histories of the Richmond Theater fire. Eyewitnesses saw her roaming the streets in her bloody white frock, so I enjoyed imaging this lead-up.

The next thing Jack knows, the curtain has lifted, the carriage breaks down in the forest, and Raymond—played by Hopkins Robertson— stumbles out. The banditti—led by Placide—are waiting to pounce, and Jack watches him use a stage whisper to quiet his men. He really is a marvel, Placide. Perhaps the most compelling villain Jack’s ever encountered. Better than Claudius and Iago and Richard III combined.

I really did have to work to get all my theatrical references just right!

“Jack,” comes a voice behind him. He turns to find Green gesturing at the stage. “Were you born under a threepenny planet?”

It took me ages to find the right line to use here. I wanted something that was appropriate for the time period and that essentially meant, "Are you a f*cking idiot?"

“What?” says Jack, glancing wildly around the stage. He’s not sure what he’s done wrong, but Green isn’t easily angered, so he must have done something.

“Why in the confounded hell is there a lit chandelier in the middle of the forest?”

Jack’s eyes drift upward, and sure enough, there the chandelier is, glowing in the dark. They’d needed it in the first three scenes, but Jack was supposed to extinguish it before Raymond set off on his ride through the forest. “I’m so sorry,” he says. “I forgot.”

“You forgot?”

Jack nods.

“You are allowed to forget any number of things. But when six hundred people are staring at a chandelier in the middle of a forbidden forest, I expect to hear more than ‘I forgot.’”

“It won’t happen again?”

“Get it out of there.”

“I can’t put it out right now,” says Jack, desperate to appease Green, but unsure how to do so without mucking up the whole scene. “I’d need to lower it onto the stage floor, and I can’t very well do that while the scene’s underway.”

It took my husband and me an entire afternoon in front of a whiteboard to sketch out exactly what happened with the chandelier. I had the inquest report and we went line by line, trying to figure out who was where and what might have reasonably happened to result in the chandelier needing to be raised into the flyspace. We’ll never know if this is exactly what happened, but I think we got it pretty darned close.

“Then raise it.”

“What?”

Mrs. Green has come over to see if she can convince her husband to lower his voice, but it’s hard to take her seriously when she’s dressed in that ghoulish nun’s getup.

“Raise the chandelier,” says Green without so much as acknowledging his wife.

“But the candles are lit,” says Jack. “It could catch the backdrops on fire.”

Green looks up into the flyspace. “They’re a good six feet away. Just let it sit up there, out of sight, until this scene is through. Then you can deal with it.”

Jack hates arguing with Green, but he doesn’t know what else to do, particularly when he remembers the broken pulley. “It may not be so easy to get back down. There’s a broken pulley, and Anderson says—”

“Is Anderson running this company? Or am I?”

Jack looks at Mrs. Green, silently begging her to intervene.

“John, the scene’s almost over. Don’t you think, at this point, it’d be better to—”

He cuts her off, and pokes Jack in the chest. “I said, raise the chandelier.”

This line comes straight out of the inquest report.

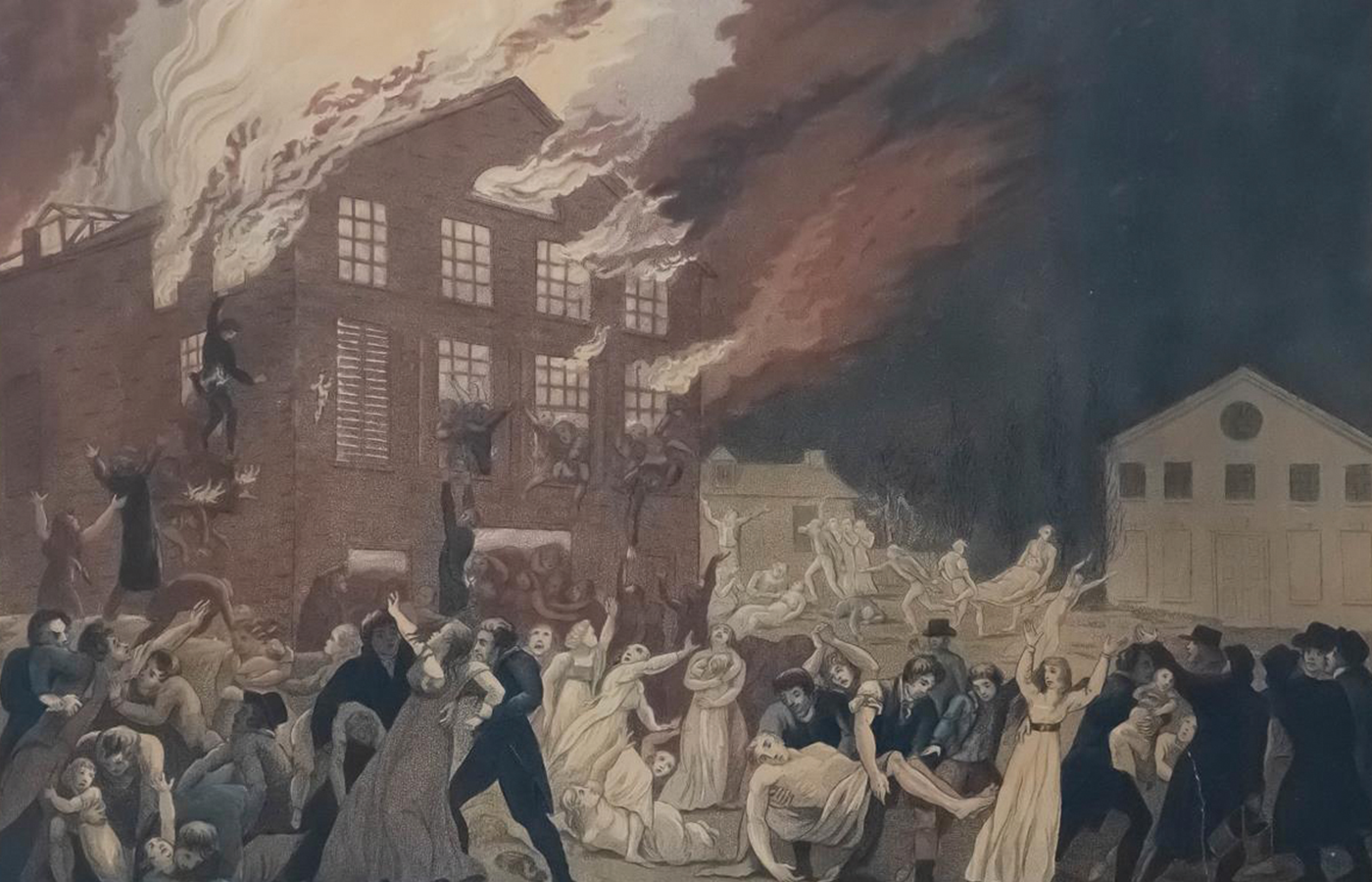

This engraving by Benjamin Tanner from February 1812 depicts the Richmond Theatre fire.

Jack nods, once, and darts off in the direction of the rigging, where he frees the chandelier’s rope from its anchor and watches as the prop glides straight up into the air. When the chandelier arrives in the flyspace, Jack anchors the rope back into place, then hurries to find Clive so he can explain the situation.

By the time Jack locates Clive, Robertson has been captured and brought to the castle, where he’s introduced to Margaretta—played by Placide’s wife, Caroline—and provided accommodations that he will soon regret accepting. Jack tells Clive about the chandelier, but he doesn’t seem concerned. “We’ll get to it,” he says. “Soon as this act is over.”

Jack watches from the wings as Mrs. Green prepares to make her entrance as the bleeding nun and close out the first act. She squares her shoulders and takes two deep breaths, and when she moves onto the boards, he could almost swear she is floating.

God, what Jack wouldn’t give to have a thimbleful of her confidence. He’s begun to dream of auditioning for a role in one of the company’s many performances; if it were the right part and he were smart about it, he could still keep up with his duties backstage. But what always stops him from even asking about it is the fear that he won’t be any good, that when he gets out onstage, in front of all those people, they’ll be able to see right through him.

Providing too much backstory can take the reader out of the story, so the key is to slide it in as subtly as you know how!

Mrs. Green arrives at center stage and faces the audience. Everyone in the theater lets out a collective gasp, and by the time the curtain closes a few minutes later, she has stolen the show. The sound of the audience’s applause is deafening.

Jack is still shaking his head in a kind of bemused wonderment, when he looks across the stage and sees Roy in the wings, tugging at the same rope Jack only recently tied off.

“Oy,” says Jack as he takes off running across the stage. “What are you doing ?”

“Twaits told me to get it down,” he says. “The candles are still lit.”

I deviated from the script a little here. There was actually a house manager named Aldus Rice who first noticed the lit chandelier and ordered it to come down. I initially wrote him into the novel, but my editor recommended cutting him because she worried that readers were going to get totally overwhelmed with the number of people backstage. I hate deviating from the historical record, but she was probably right.

“Stop!”

Roy doesn’t stop, and Jack watches the chandelier begin to list. “Didn’t Perry tell you?” Jack shouts, but he doesn’t have time to explain. The harder Roy tugs on the rope, the wider the chandelier swings.

Jack is terrified the flames will come too close to the backdrops and set them alight. “I’ll climb up there. I bet I can reach it. Just stop what you’re doing!” He makes for the ladder and is up in the carpenter’s gallery when he sees that, in fact, Roy has not stopped pulling at the rope. Instead, he’s been joined by Perry, who is putting his whole body into making the rope move.

Jack climbs out onto the nearest rafter, shimmying over the heads of the two carpenters. Splinters of wood slice into the meat of his hands. When he is as close to the chandelier as he can get, he takes a deep breath and tries to blow the candles out, but the chandelier is too far away for the flames to even flicker. So, he licks the pads of his thumb and forefinger and stretches his hand into the air, as far as it will go. The chandelier is just out of his reach, but the way the thing is spinning, it’s like a pendulum; Jack just has to be patient and eventually it will arrive in his hand.

Another paragraph that barely changed.

He wants to try to get Roy’s and Perry’s attention, wants to tell them that he has the situation under control, but the second act is underway. Perry begins to jostle the rope, a different kind of movement that Jack immediately realizes is no good. “Stop!” he yells down to him, not caring who hears him, but it is too late—the chandelier has tipped sideways and Jack watches in horror as it kisses the edge of the nearest backdrop.

What happens next is all sound and light. Jack inches backward, along the rafter and away from the flame, as fast as he can. By the time he has made it back to the carpenter’s gallery, Perry is up there, waving at the back- drop and shouting instructions at Jack. “Help me cut this down!”

Perry has a knife, but Jack has none, and he watches as the carpenter saws at one rope and then another. The fire licks its way to the top of the backdrop and threatens to touch the ceiling, which is nothing but timber and sap.

“Do something, kid!” says Perry, a tangle of ropes in his hands, but Jack can’t move, can’t think of a single thing to do. He barely knows how to make himself useful when everything is going right.

Below him, onstage, Robertson looks up into the flyspace, his eyes widening into orbs. The man’s bottom lip trembles, as if he is trying to make words but can’t force them past his lips. Finally, he pulls his eyes away from Jack and Perry and the flames that rage behind them, turns to the audience, and flaps his arms. “The house,” he yells, finding his voice at last. “The house is on fire!”

This is indeed what Hopkins Robertson said to the audience, when he realized they needed to evacuate the building, and it was such a powerful line it became the title of the novel.