Arts & Culture

Out of the Past

Sisters Enjoli and Sesha Joi Moon are using their nonprofit, the JXN Project, to explore the lost grandeur of Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood

Around lunchtime on a June Monday at East Broad and Third Streets in Richmond, Virginia, the temperature is somewhere between so hot and late July in hell. Sesha Joi Moon, Ph.D. (B.A.’05; M.S.’08; Cert.’09), despite being short enough to make phone books relevant again, has heaved a foldable wagon from the back of her SUV.

The Richmond native is using the wagon to move a some-assembly-required shelf and boxes of branded ephemera into the first headquarters of the JXN Project, the nonprofit she founded with her older sister, Enjoli.

Enjoli is the assistant director and director of programming, and Sesha is the executive director of this undertaking, created two years ago to tell the forgotten, lost and quashed stories of Jackson Ward. Stylized “JXN” by the sisters Moon and once home to banking magnate Maggie Walker and dancin’ movie star Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Jackson Ward is Richmond’s premier historically Black neighborhood and one of America’s most vital, lucrative and fabulous Black enclaves not named Harlem.

Familiar with white gloves, dissertations and how to charm archivists, Sesha, 39, who has a Ph.D. in public policy from Old Dominion University, also serves as JXN’s director of research. And at this broiling moment, she’s in charge of moving day, too.

The JXN Project has leased a small, one-windowed rectangle, accented with exposed brick, on the third floor of Gather, one of those trendy coworking spaces whose forebears escaped Brooklyn some time in the past decade. It’s just across Broad from Jackson Ward proper.

After achieving 501(c)(3) status on July 1, 2021, this is, perhaps, the most official step for the upstart organization, which has already starred in a 9-minute, 17-second PBS news segment and banked a $1.5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation, giving JXN a flush push toward its $5.6 million fundraising goal.

Wagon-schlepping help is offered. Sesha says she’s got it.

What would become the JXN Project coalesced during the summer 2020 protests and came to life the ensuing December when the pandemic chased Enjoli’s Richmond-based Afrikana Film Festival online. She asked her little sister the researcher (and, as of this summer, the director of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Office of Diversity and Inclusion) to find 10 facts about Jackson Ward for the festival. JXN grew from Sesha’s stumbles over: Who is “Jackson”?

“Little did we know, that would not be an easy answer,” says Sesha, now out of the heat and on Gather’s third floor. She has commenced with the setting up of the office. “Actually, it was an easy answer. We just didn’t recognize it would take so much research to get to the easy answer.”

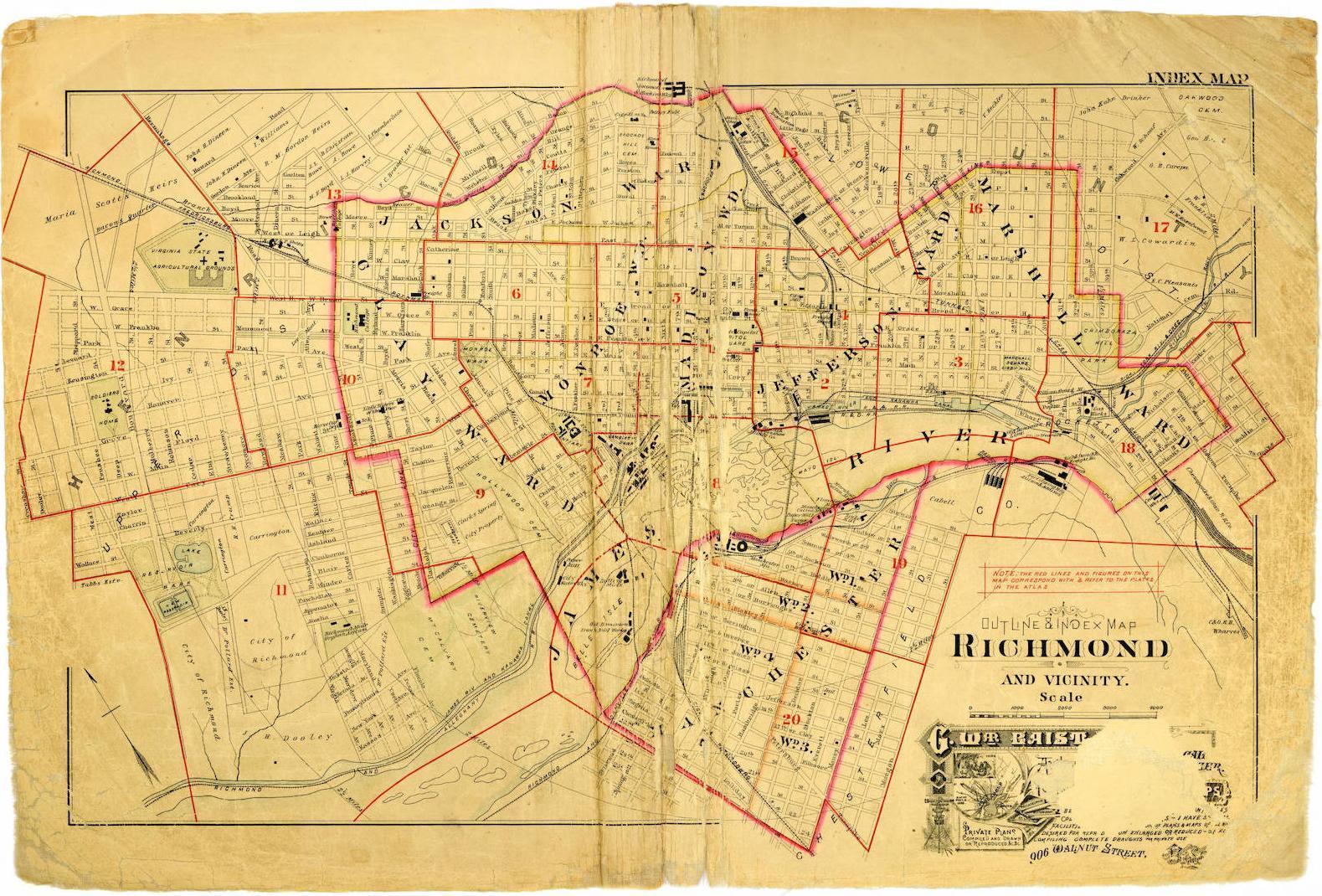

Because of the JXN Project’s work in the archives of the Library of Virginia and The Valentine museum, we now know, as certainly as we can, that city potentates — many still practicing Confederates — created Jackson Ward on April 17, 1871, to kneecap Reconstruction and gerrymander Black suffrage into oblivion. But the ward, likely named for Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson (so says JXN research), bested its origins and boomed for decades, until the city and state vivisected it in the 1950s with what became Interstate 95. It was a thorough maiming, though not quite fatal.

The Moon sisters are descended from Jackson Ward on their mother’s side — Enjoli’s first apartment was a block from where their grandfather grew up on Marshall Street — and it’s those ancestors, both blood and not, that power the JXN Project and concentrate it on Black narratives and Black achievement.

“I believe we’re guided by ancestral power,” Sesha says. “I don’t believe that anything that they have or they need for us to complete, that someone else can stand in the way of. ... Do what the ancestors assigned you to do, and all will work itself out. I genuinely believe that.”

Sesha, left, and Enjoli Moon. (Keshia Eugene)

At JXN HQ, Sesha is building the shelf. It’s one of those industrial-looking, chain hardware store affairs, the four black shelves adjustable around four poles that seem like refugees from the Island of Misfit Javelins. The shelf will anchor HQ’s back left corner and display JXN-branded buttons, mugs, sweatshirts, etc.

“And of course I did it backwards,” Sesha says.

The ancestors seem to be sitting this part out.

But shelf assembly does seem a bit beneath the venerated dead, those gone-before and now gone-on that make the JXN Project something more than its tax designation. They have consecrated Sesha and Enjoli Moon divinely charged griots, tasked to celebrate and evangelize Black excellence, past, present and future.

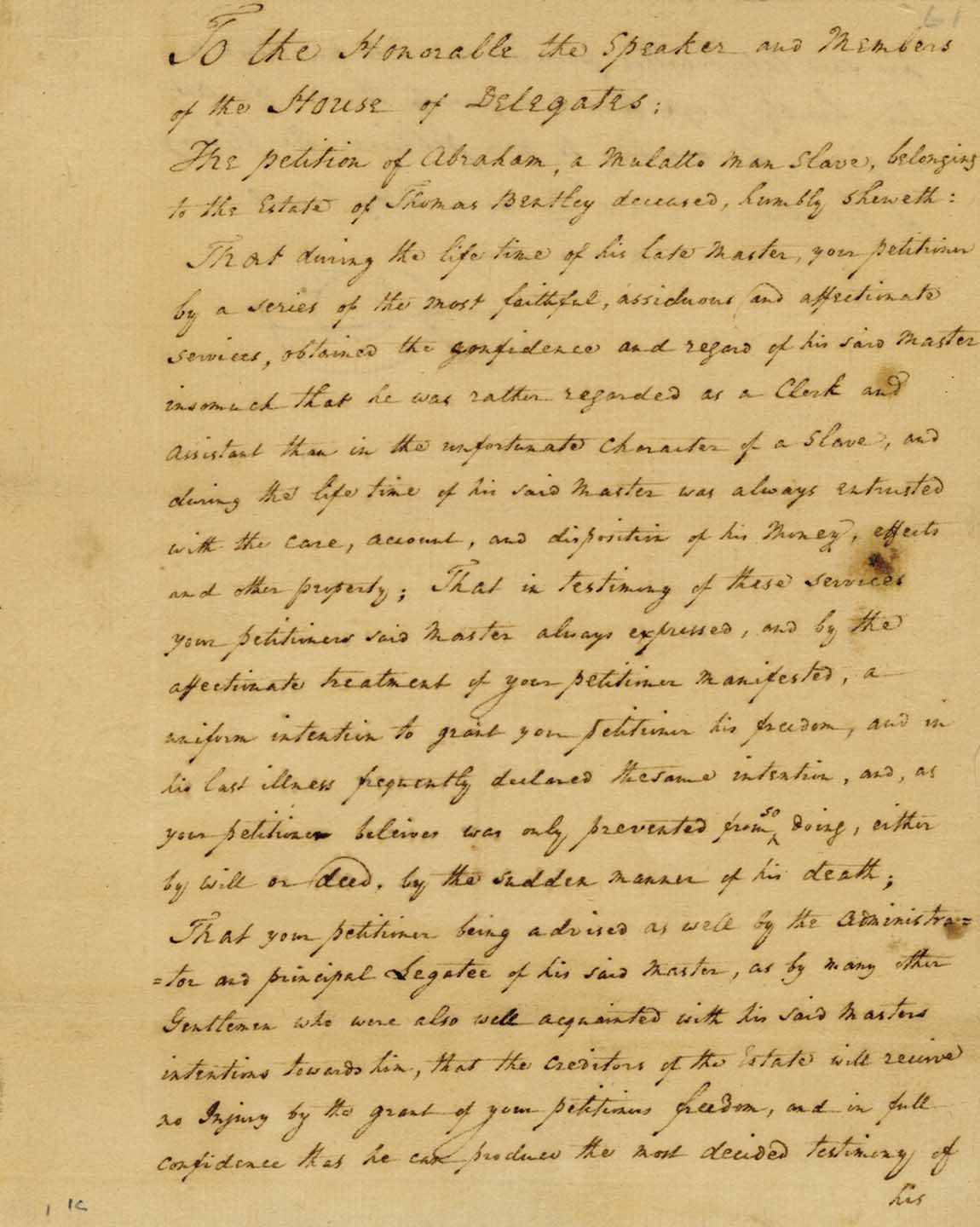

“Abraham Peyton Skipwith,” Sesha says — no, declaims! — invoking the Jackson Ward Black man who, with a vouching from Declaration of Independence signer Benjamin Harrison V, manumitted himself in 1789. “The most anyone knew was that he was the first Black homeowner; he built a gambrel-roof cottage; we’re done here. His ties to the Founding Fathers? Unknown. He’s one of the first Black, known gentlemen with a will? Unknown.

“While some people knew that the home was moved out to the former plantation” — during the highway’s construction in the late 1950s, a white family had the circa 1793-built house relocated from Duval Street in Jackson Ward to nearby Goochland County, where it stands today, although Skipwith has been all but remodeled out of it — “that also was not common knowledge because record books said it was demolished. So, especially people from the community had no clue that his home was picked up and dislocated. We feel very honored to have been the ones that the ancestors chose to help amplify [Skipwith’s history].”

This is some of the forgotten history the JXN Project helped unearth, earning plaudits from officials at the Library of Virginia and The Valentine as well as the Black History Museum and the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, a national organization founded in 1977 to help Black people exhume their obscured ancestries.

Until recently, American history and Black history have been, with some selective, sanitized exceptions, mutually exclusive. Black stories were censored and that necessitates JXN’s work. In Virginia, this propaganda campaign had a name: the Virginia Way.

A bit of Lost Cause-flavored flummery, it’s the name given to Virginia’s traditional racial and social hierarchy. Atop were the patrician white families who told themselves they enforced a genteel moral code that instilled Southern politesse and kept Virginia society in good (and antebellum-shaped) order. The Virginia Way — named by early 20th-century Robert E. Lee hagiographer, newspaperman and local high school eponym Douglas Southall Freeman — also smothered Black enterprise, Black stories and Black humanity.

“‘It was willful suppression. That’s the Virginia Way,’” says Sesha, quoting local activist and Jackson Ward historian Gary Flowers. Since 2016, he’s led “Walking the Ward” tours of the neighborhood.

By now, the Virginia Way’s vanguard has either died out or been smote by social progress and Richmond’s now-widespread Confederate apostasy. Still, there’s a hangover. That’s why you probably haven’t heard of all-star Richmonders Giles B. Jackson or John Mitchell Jr., and why your knowledge of Maggie Walker is likely defined by a few questions on a 10th-grade social studies test.

It’s also why you don’t know the story of Abraham Peyton Skipwith.

WHILE WORKING on her classic 1950 book “Old Houses of Richmond,” Mary Wingfield Scott went poking about in some archives and found Abraham Skipwith’s will. Written in 1797 and lasting three detailed pages, it not only bequeathed his wealth, property and prosperity — notably cash, the cottage, furniture, a gun, a horse and buggy, livestock, and gold and silver — to his free children but also advised them on investments and interest rates.

“One of the things that was cool about him was he’s working with these high-powered elites in Virginia who knew how to manipulate money,” says Gregg Kimball, the Library of Virginia’s director of public services and outreach. He’s also the author of “American City, Southern Place,” a history of antebellum Richmond, and a JXN Project confidant. “It’s this incredibly complicated three-page will you just don’t see [from] a person of color in this time frame. He had these business skills that he developed from basically being a kind of business manager.”

Skipwith’s will is housed at the Henrico County courthouse, while his 1785 Founding Father-endorsed petition for freedom to the General Assembly has been stowed at the Library of Virginia for years and years. Neither have been oft sought. And if they were, the researcher wasn’t studying those seminal documents the way the JXN Project would. Scott read the will, but the intrigues and interests of a mid-century architectural preservationist lead only to specific places.

“Her main interest was not Abraham Skipwith. It was his house,” Kimball says. “It was one of the earliest houses in the city. I think she does have, maybe, a quote or two from it, but you know, that’s the thing about researchers: It all depends on who’s looking at the document. How do you unpack it? That’s something I think [the JXN Project] did incredibly well. They approached it very differently than maybe a white scholar would — and Sesha’s an excellent researcher. One of things she does that I wish all researchers knew to do is ask a lot of questions. She has a research background but not necessarily in history, so a lot of it was just like, ‘Oh, this guy Abraham Skipwith is getting his freedom. Was that typical? Did other people seek emancipation at that time?’”

This is how a cottage came to supersede a man.

“Black history is American history,” says Mary Lauderdale, the director of collections at the Black History Museum and a friend of the Project. “But it’s been not taught, under-taught, minimized, and it should be a basic fabric of American history, but it’s not. But every time you turn around, you should see that it always should have been. … The Moon sisters are making sure that some of this history does not disappear.”

The JXN Project does much of its research the prim, old-fashioned way: descending, white-gloved, into archives to trudge through ledgers, tomes and volumes while reading lots of stuff that smells like your grandmother’s couch. Sesha, after moving day, had plans to pass her late afternoon at the Library of Virginia. JXN has assembled about 65% of Skipwith’s life but crusades on for the still-shrouded 35%, most of which has to do with his early years.

The Moon sisters’ work is part of a grander research trend. Black history has become less and less and less separate from American history, starting in the late 1960s as part of the civil rights movement — San Francisco State, in 1968, founded the first Black studies department in the United States — and evolving from a genre subject to a varied and vibrant field, one of late punctuated by Nikole Hannah-Jones’s 1619 Project. This also coincides with demographic and pop culture changes that have mainstreamed (and monetized) Black stories.

“People are seeking the truth, and I think there’s a shift toward truth-telling — authenticity,” says Viola Baskerville, who, 10 years ago, helped charter the Richmond chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society. It now has 37 chapters nationwide.

“Not being lied to anymore, understanding human value and human worth and searching for that,” Baskerville continues. “I think the pandemic has made it that people have turned introspective. I think there have been so many more resources online. People have time and they’re starting to read and do research. So, I think, yeah, there’s a tremendous shift that has happened. My question is: What’s going to become of this shift? This awakening? Enlightenment, if you will? What’s going to come and is it going to be sustainable? Are you going to take this information that we’ve discovered, change systems — change our social systems? Change our economic systems? Change our environmental systems? Change our cultural systems so that we understand that there is a value toward looking at these multicultural and diverse perspectives?”

Abraham Skipwith’s house, shown here in 1956, was moved to a farm in Goochland during construction of the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike in the late 1950s. (Edith K. Shelton, courtesy of The Valentine)

Access drives this new (and maybe even golden) age. Classic research, the sort conducted with antique documents kept behind large doors with large locks, can be prohibitive.

“For too long — and I would say this is probably a problem, too, not more than 25 or so years ago — even archivists themselves looked at their collections as little fiefdoms,” Kimball says. “The idea was more to protect the collection than it was to necessarily help people explore. A lot of things have changed.”

Kimball cited the rise and democratic power of “public history.” Sojourns in faraway lairs are no longer mandatory. Many records have been digitized, accessible to anyone with Wi-Fi, curiosity and spare time, although some of the old biases are still only mostly dead.

“You have to ask the question of why certain records were digitized and which were not,” says Bill Martin, director of The Valentine and another JXN confidant. “It tends to be the history we focus on.”

That’s a barrier specific to Black history. Black history itself is another.

“The complexity for African American research is that you get to a point where there are no records,” Baskerville says. “You get to the point of enslavement, and individuals are considered property, and then you have to think: Where could the records be that would relate to the record that I’m looking for?”

Baskerville, who served in the Virginia House of Delegates and is a former member of Tim Kaine’s gubernatorial cabinet, has researched her provenance for more than 35 years, enduring frequent thwartings by the persistent whiteness of American history. A lot of Black history is veiled behind the 1870 census, the first one after emancipation — or was, until mail-order DNA testing.

Baskerville joined Ancestry.com about 10 years ago, and through that membership, she’s made it into the fuzzy dimness beyond the 1870 census and found her maternal great-grandmother, Jane Gentry Johnson. Previously, all Baskerville knew about Johnson was her first and married name (Jane Johnson), that she’d been enslaved in Louisa County, 50 miles west of Richmond, and that she died in 1916.

With her DNA parsed, Baskerville now knows Johnson’s maiden name (Gentry), her birth year (1844) and where she was born (Sevier County, Arkansas). Baskerville, again through DNA, also has connected with previously unknown distant relatives, some the descendants of her great-grandmother’s enslavers. Baskerville says some reply to her Ancestry.com-facilitated messages and some don’t. Currently, she’s after the bill of sale that sent Johnson as a child from southwestern Arkansas to central Virginia. It’s a morbid, heart-bruising quest that makes organizations such as the JXN Project and the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society essential.

“It gives people a platform, a venue, a space, to understand the technical parts of research but also to be supportive of each other when they break through and find these surprise findings,” Baskerville says.

It is sacred work.

“We’re going to lift up the ancestors and say what they contributed to our community and our organization,” she continues. “We can say that not only do Black lives matter, but Black ancestors matter. We can start to reconstruct the village. We can start to become whole again because no longer is your identity in question, but you have some sense of the pieces that got you to the point that you are.

“I do the work because I think it’s important for people to understand the truth. I think it’s important that African Americans contributed not only so much in the sense of labor and resources so this country could move forward, but in contributing those resources, our whole being spiritually and our families were torn apart. So, for me, it’s a sense of healing. It’s a sense of reparations — spiritual reparations, if you will. It’s a call out to those organizations and those private entities and those archives that hold information to say we need to open these archives and we need to share it with people.”

Abraham Peyton Skipwith’s name is now on Judah Street in Jackson Ward between Leigh and Duval streets, the latter where Skipwith’s house once stood. His name is there, in part, because of the JXN Project.

“I think their work is pivotal to awakening a whole younger generation to be interested in not only African American places and history but of African American luminaries,” Baskerville says. “It’s to make this bridge between the past and the present generation so that information is not forgotten.”

An aerial view of construction of the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike in 1958. (Courtesy of The Valentine)

IT’S STILL JUNE, still abusively hot, but it’s Tuesday, and there’s an old Black man waiting at the window of Sugar’s Crab Shack, a fried soul-and-seafood joint inhabiting the repurposed husk of a late and delicious local cheeseburger chain at the corner of Chamberlayne and Wickham in Richmond’s Northside.

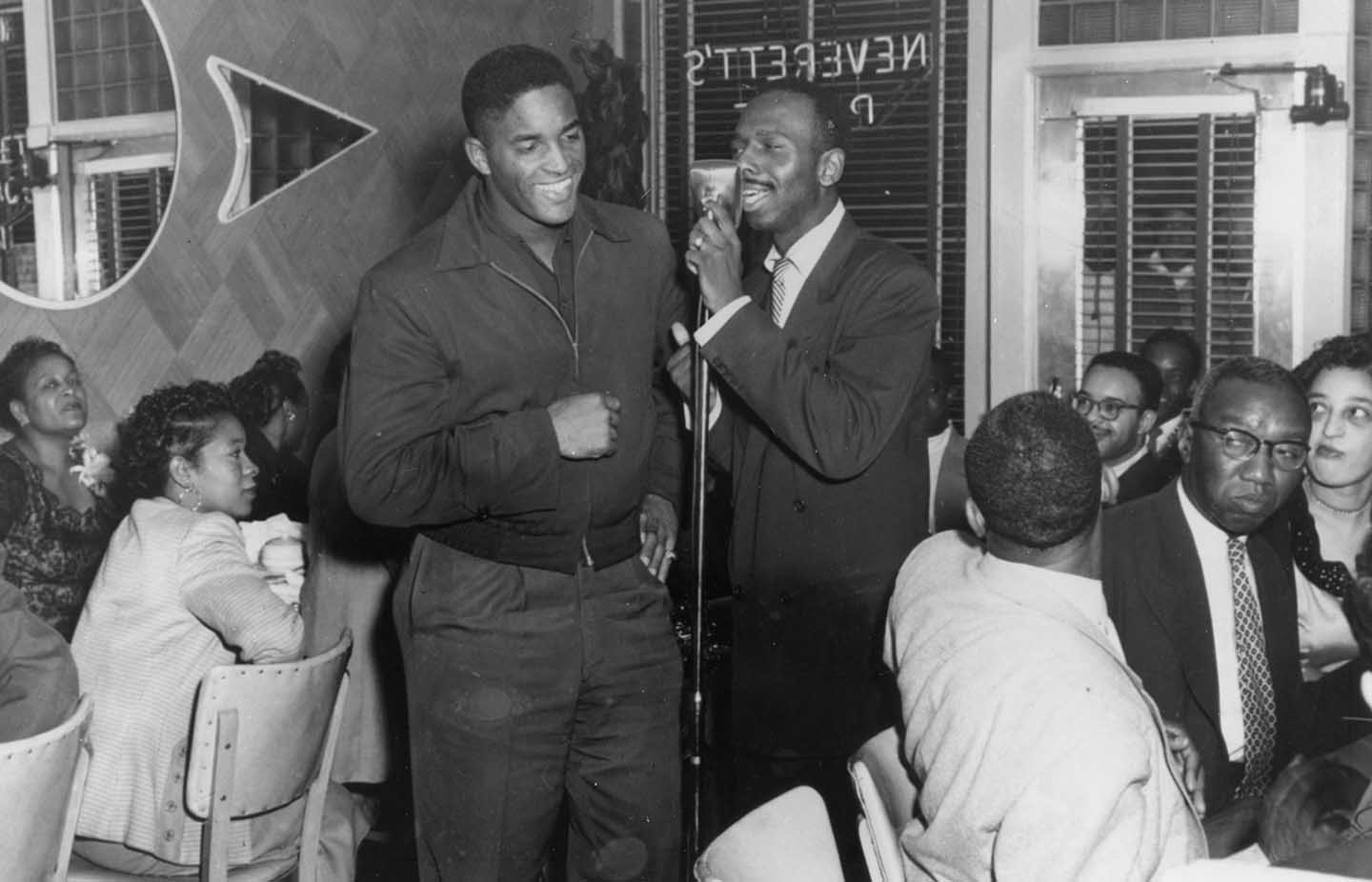

Sugar’s is owned by, and named for, Neverett “Sugarfoot” Eggleston III, a scion of Jackson Ward’s mighty Eggleston family. They’ve owned hotels, restaurants, service stations and lots and lots of property in the neighborhood since Neverett Eggleston Prime opened the Lafayette restaurant in the late 1920s.

The old man’s waiting for lunch, wearing a Cleveland Cavaliers hat and eyeballing some dark clouds in the tropospheric distance. They’re just beyond the last place the sky has managed to stay blue. He’s talking about the weather, in the way old men do, but then, he’s not.

“I’ve never seen a time with so much change,” he says.

Across Sugar’s stone patio, Enjoli Moon, the JXN Project’s assistant director and director of programming, is at a cement table under a yellow Googie umbrella — the restaurant’s past life intruding on its present.

Enjoli didn’t hear the old man but she’s talking about change, too. She’s talking about the uprising of summer 2020. She calls it the “year that changed the world.”

“It cleared out a pathway that people have been chopping down trees on for a very long time,” she says, having a fried fish lunch and answering the occasional telephone call. Enjoli is nothing if not popular. The Afrikana Film Festival is only a few months away.

“They were able to come through with a stick of dynamite and move a lot of the stuff out of the way, and I think it’s because of the clearing of that pathway that all those people did. It lives on a continuum, and indeed JXN Project has benefited from the shift that 2020 brought about. Ten years ago, it couldn’t have existed. I don’t know that we would’ve been able to do the work that we’re doing, the way we’re doing it.”

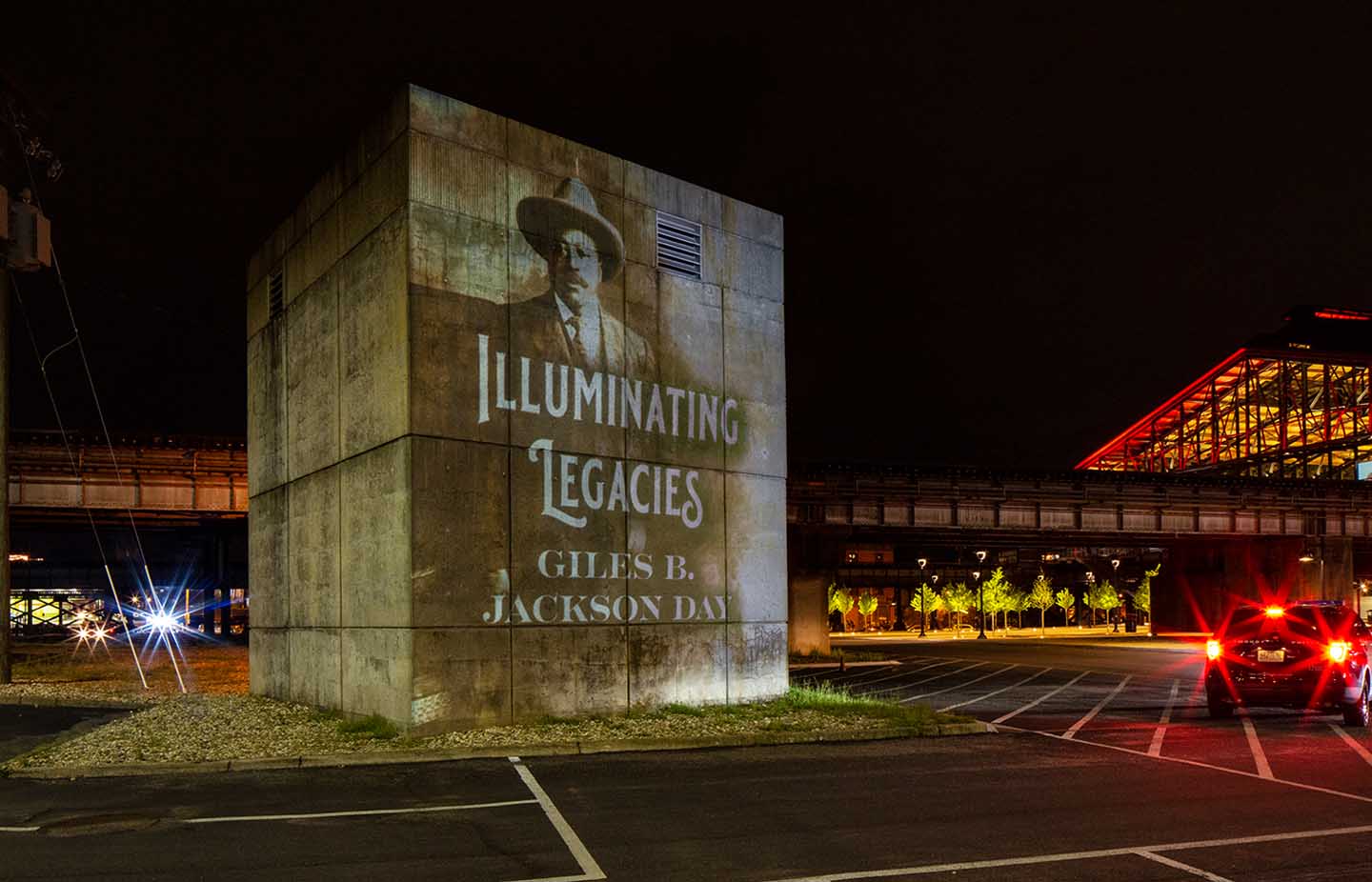

To mark Jackson Ward’s 150th anniversary, the JXN Project organized “Illuminating Legacies: Giles B. Jackson Day” on April 17, 2021. The festivities included food trucks, art, trolley tours and 12 spotlight projections commemorating the neighborhood’s people, places and history. Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney also declared April 17 Giles B. Jackson Day. Jackson, a previously suspected Jackson Ward namesake, is the first Black man to practice before the Virginia Supreme Court. That was 1887. He died in 1924.

With the help of the JXN Project, though, a segment of Clay Street has been dedicated to Jackson, denoted with a ceremonial brown street sign and starting at Second Street. Colloquialized “The Deuce,” Second is the neighborhood’s historical thoroughfare where the Eggleston Hotel once stood and where the Hippodrome Theater still does. Jackson is one of 15 such hallowed ward citizens, along with Skipwith, to receive a sign, arrayed under the familiar green ones that bear the grim names of dead Confederates and dynastic enslavers.

“I do think that this sphere of interest has opened — has widened,” Enjoli says. “And so 2020 did that through the lens of talking about Black equity, right? Or the lack thereof in our society, but then very much in Richmond, Virginia, since so much of that conversation leaned into the things we choose to symbolize and the narratives we choose to elevate and celebrate. People realized, Oh, I need to shift. I need to widen my aperture. I need to shift my lens a bit. And the people being able to do this, in a space like this, because they realize that all the street names, like Wickham” — she points at the lower of the two green signs overlooking Sugar’s — “and you know that white Confederate history is deeply pervasive in the space we live, and that has informed the stories that you heard. It has informed the stories you’ve been told and who’s been able to tell them. That reality, just being brought up to the fore for everyone to see and have to embrace, I think it was the catalyst, or it was the foundation — it was a strong foundation — for JXN to be able to land on. It was quite serendipitous that the Project came when it came and landed when it landed.”

The JXN Project has presented, virtually, to Viola Baskerville’s chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society and hosted programs at the Library of Virginia, where in a few years there are plans for a Skipwith exhibit built on JXN Project research. JXN also is moving to rededicate the ward for Giles.

“I think it’s fair to say that it is something ever evolving,” Enjoli says of the JXN Project. “We didn’t set out to start it. It’s all kind of presented itself to us, and we decided to take up the charge. As it exists right now, we are focused on unearthing the undertold, or untold, histories of Jackson Ward, with a specific focus on the pre-1871 reality of Jackson Ward and the space that would become it.”

She also wants JXN to be an example.

“This is how you can take your own family’s history or your own community’s history in your own hands,” Enjoli says. “You don’t have to be intimidated by this. You don’t have to have a Ph.D. in order to do this — although Sesha does — right? There are plenty of people who have been doing grassroots research for generations and have unearthed really important information. To be able to give people the tools they need to access information is really key.”

“Black history is American history. But it’s been not taught, under-taught, minimized, and it should be a basic fabric of American history, but it’s not. But every time you turn around, you should see that it always should have been.”

Enjoli, who’s the assistant curator of film and special programs for VCU’s Institute for Contemporary Art, is more the artsy sort than her type-A sister Sesha the academician, attuned not just to the hants and ancestors watching Jackson Ward from old shadows but also to …

“It’s cosmic direction is what I would call it,” Enjoli says.

About 20 years ago while driving with her father on Second Street — a street, she stresses, she did not frequent — she says, a woman approached the car and told her a new restaurant was hiring servers.

“I’m not all interested,” Enjoli says. “But ... I was looking for a job. I had never worked in a restaurant and didn’t have any desire to do it. I wouldn’t have pulled over, though, if my father wasn’t in the car. Because my dad was like, ‘Oh, that’s Neverett’s son’s place.’ Now, it just so happens that the man who owns this restaurant, his father and my father are best friends.’ So he’s like, ‘Oh, that’s Sugarfoot’s place. Pull over.’”

She didn’t want to.

“He’s like, ‘I just wanna see it. Pull over so I can holler at Sugarfoot.’”

She still didn’t want to, but she’s a good daughter.

“All right. Cool,” Enjoli says. “I pull over. I get to talking with them, and the next thing you know, I’m at the meeting a couple days later and then I’m there on the first day of work. The place absolutely changed my life — it changes the entire trajectory of my life. It created a foundation for me that served as the catalyst for every other thing that I am doing, down to the level of connectivity to Jackson Ward.”

Sugarfoot’s restaurant was Croaker’s Spot, the acclaimed and now multi-location seafood place that opened in 2001 on Leigh Street in Jackson Ward before moving in 2009 to Hull Street, just across the river. Enjoli worked at Croaker’s for 10 years, starting as a server and eventually becoming operations manager and head of marketing. Croaker’s, she says, along with the encouragement of Eggleston III, led Enjoli to create Richmond’s Afrikana Film Festival in 2014. The sixth edition, held at Maymont Nature Center, the Carillon and online, happened in September and showcased a variety of feature-length and short films, headlined by 2021’s “Summer of Soul,” a critically esteemed documentary directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival.

“It’s been, I don’t know, like a cosmic 360 for me to land back here,” Enjoli says. “It just feels, I don’t know, like a reminder that we are not here by ourselves. There are things that are at work within us that we can’t always feel and touch, but it doesn’t make it not less real. And, you know, those moments in my life have served as confirmation of that, all the way down to and within us doing our own Jackson research about these other people and figures.

“We recently learned that Sesha and I have roots in Jackson Ward. My mom goes to the garage one day and pulls out a box of pictures — just pictures dating back to 1882. We’d never seen these.”

The part of the sky that stayed blue isn’t anymore, and the dark clouds, once in the distance, are overhead and looking like they want to give the yellow umbrella a workin’-over. The old man, though, seems to have gotten his lunch.

“The history of this country and the history of this city and this state has been around suppressing Black narratives, especially ones that are rooted in concepts of liberation — self-liberation,” Enjoli continues. It’s raining now, a classic summer afternoon thunderstorm. “When we come across something that affirms our humanhood and the fact that we have found ways to be autonomous individuals, whether that be in small ways or larger ways, like Skipwith, I’m never surprised but I feel excited in who I am and who we are and who we’ve always been.

“The charge gets stronger to do whatever you’re called to do. Whatever you feel called to do, that charge, it’s a buildup. You realize you’re part of a continuum. You’re part of a longstanding legacy. When you find people like Skipwith and some of the other stories that get unearthed, you realize that you aren’t that far removed from this. This isn’t like some person that you read about in a book. This is part of who I am.”

BACK AT JXN PROJECT HQ, Sesha Joi Moon has erected the shelf, admonished an especially forward housefly — “Of all the offices, you found your way into 310” — and is arranging the merchandise.

It’s past lunch now, even though there has been no lunch, and she’s telling a story from when she attended Saint Gertrude, an all-girl Catholic high school in Richmond, then not far from where she grew up around Byrd Park. The school has since decamped to the far, far West End.

“We went to Monticello — I’ll never forget this,” she says, referring to Thomas Jefferson’s plantation on the side of a little Charlottesville mountain. “They gave us the most elaborate tour of Thomas Jefferson and all the great deeds he did. And then we get to Mulberry Row, which is where the enslaved quarters used to be, and they told us to imagine it, because they had been torn down — they just told us [to] close our eyes and imagine. To see the juxtaposition of them keeping everything, down to a spoon, from Thomas Jefferson; and then for the people who built this place, I’m supposed to close my eyes and imagine their experience?”

She pauses, but not for long.

“I’ll never forget. There’s a talent show coming up at Saint Gertrude. I wasn’t signed up originally but I signed the hell up and I went and I talked about that. I did not appreciate that experience because I did not see myself in that field trip, and it’s so crazy because I remember being so —” she takes another moment. “All the emotions. Hurt, angry, disappointed, annoyed. I don’t know. I did carry that memory. Vividly.”

It was a brush with some of the remnants of the Virginia Way, now mostly scraped into the ether of an abjured past. Mulberry Row has been partially reconstructed, and the stories of all those human beings forced to work the third president’s lands are no longer ancillary to the fine china. They are quintessential to Monticello’s history and Jefferson’s legacy, as the JXN Project plans for Abraham Peyton Skipwith to be to Jackson Ward’s.

“He actually says do not call me the ‘unfortunate character of a slave,’” Sesha says. “That’s a Black man saying that. In 1785.” It’s unclear how officials reacted, although we can guess. “But to have that audacity — which is why we’re so excited to share this story about Skipwith. Because I will say, one thing about Jackson Ward that is so powerful is these were stories of Black excellence and empowerment. A lot of times, when we hear about Black American experiences, it’s from a place like Black trauma. Skipwith gives us an opportunity to tell a different narrative — one of self-determination and autonomy. To read his legislative petition and his will, it is a Black man who dared to say, ‘I’m American, too!’ — and this is during the American Revolution. It’s all this talk of freedom, independence, liberty. This is when this man is alive in Virginia, where most of the people who wrote that document are living and he’s saying, ‘Well, I need a part of that, too, and I’m going to pursue it.’”

Abraham Skipwith's petition for freedom. “He actually says do not call me the ‘unfortunate character of a slave,’” Sesha Moon says. “That’s a Black man saying that. In 1785. To read his legislative petition and his will, it is a Black man who dared to say, ‘I’m American, too!’” (Library of Virginia)

Skipwith, whose birth date is unknown, was sold at least once before his 1789 manumission. He has become the JXN Project’s marquee priority. It plans to reconstruct Skipwith’s house in Jackson Ward along with a museum, research center and outdoor event space, hence the $5.6 million fundraising goal. This potentially will coincide with a larger resurgence for Jackson Ward, which has of late rallied from its splicing 64 years ago and the subsequent dark times aggravated by desegregation, suburban growth and various redevelopment projects.

The city of Richmond is in the “feasibility study” stage of reunifying the neighborhood by turning several blocks worth of interstate into a tunnel and using the tunnel top to rebind Jackson Ward. The federal government also has debuted a $1 billion program — its funds available to those applying with worthy causes — dedicated to reconnecting neighborhoods, not long ago demeaned as slums, similarly halved by 20th-century highways in the alleged name of progress.

It feels like all of this could be a movement. Sesha wants it to be more.

“I pray that JXN is part of a paradigmatic shift where we take control of trying to uncover our own stories,” she says. “We’re not experts on Jackson Ward. We’re standing on a lot of people’s shoulders who have done past research. That’s important to us. That’s important to acknowledge. We aren’t Jackson Ward gurus. We’re just two Black girls from Richmond who have found they have some ancestral alignment to Jackson Ward, and we’re just assigned to do this work.”

The office is unpacked. The little rectangle is arranged, a desk at either side of the exposed red brick, two swivel chairs, and the now no-assembly-required shelf displaying the buttons, mugs and sweatshirts. On the top shelf is a framed black-and-white portrait of Enjoli and Sesha.

If the office were on the other side of the building, it would look out on Jackson Ward, the once, future and, perhaps, forever throne of Black excellence in the South.

Sesha looks around and she smiles.

“Open for business, right?”